Archive

State law that boosted human services funding has helped provider CEOs more than direct-care workers

A 2008 state law, which substantially raised funding to corporate agencies running group homes for people with disabilities, has resulted in only minimal increases in wages for direct-care workers in those facilities, according to a new report from the SEIU Local 509, a Massachusetts state employee union.

Since the law known as Chapter 257 took effect, the average hourly wage for direct-care workers rose by about 14.8 percent to just $13.60 in Fiscal Year 2016, according to the SEIU report, which was released last week (and got little media coverage, btw).

In contrast, the report noted, the law helped boost total compensation for CEOs of the corporate providers by 26 percent, to an annual average of $239,500.

According to the SEIU, raising wages of direct-care workers employed by provider agencies was a key goal of Chapter 257, and yet those workers “are still struggling to earn a living wage” of $15 per hour. The union contended that the funding increases made possible by Chapter 257 “did not come with any accountability measures, leaving it up to the private agencies to determine their own spending priorities.”

The SEIU report found that human services providers in the state received a total of $51 million in net or surplus revenues (over expenses) in Fiscal 2016, which would have been more than enough to raise the wages of all direct-care workers to the $15-per-hour mark. Yet, the providers have chosen not to do so.

Last week, the state Senate approved a budget amendment that would require human services providers to spend as much as 75 percent of their state funding each year in order to boost the pay of their direct-care workers to $15 per hour. The amendment had not been approved in the House, so it will now go to a House-Senate conference committee.

The SEIU report provides confirmation of a report by COFAR in 2012 that direct-care workers in the Department of Developmental Services’ contracted system had seen their wages stagnate and even decline in recent years while the executives running the corporate agencies employing those workers were getting double-digit increases in their compensation.

In January 2015, a larger COFAR survey of some 300 state-funded providers’ nonprofit federal tax forms found that more than 600 executives employed by those companies received some $100 million per year in salaries and other compensation. By COFAR’s calculations, state taxpayers were on the hook each year for up to $85 million of that total compensation.

The SEIU report stated that during the past six years, the providers it surveyed paid out a total of $2.4 million in CEO raises. The highest total CEO compensation in the union’s survey was that of Seven Hills Foundation’s CEO who received a total of $797,482 in Fiscal 2016. Seven Hills received $125 million in state funding that year, with most of that funding coming from DDS.

The SEIU report stated that the average direct-care employee at Seven Hills makes just $12.47 per hour, more than a dollar less than the average wage for workers across all the organizations analyzed in its report.

Vinfen, the third largest provider in the state, provided its CEO with a total of $387,081 in compensation in Fiscal 2016. Vinfen spent a total of $1.7 million on compensation for its top five executives in that fiscal year.

The potential for double-digit increases in CEO compensation was not mentioned by provider-based advocacy organizations that actually sued the then Patrick administration in 2014 to speed up the implementation of higher state funding under Chapter 257.

According to the plaintiffs in the lawsuit, the higher state funding was needed quickly in order to keep up with the rising costs of heat, rent and fuel, and to increase wages to direct-care staff in order to reduce high staff turnover.

In comments in support of the provider lawsuit in 2014, one key provider lobbyist contended that time was of the essence in boosting provider funding. “…Every day that full implementation (of Chapter 257) is delayed, the imbalance and the unfairness grows,” the lobbyist said.

Yet, according to the SEIU, the providers made 3.2 percent, 2.7 percent and 2.3 percent respectively in surplus revenues on average in the Fiscal 2014, 2015 and 2016 fiscal years. The imbalance that existed was actually between executive-level salaries and direct-care wages in those provider organizations.

As a result of the lawsuit, both the Patrick administration and the incoming Baker administration approved major funding increases to the provider-run group-home line item in the DDS budget, even as it was becoming clear the state was facing major budget shortfalls in the 2015 fiscal year.

“This all suggests,” last week’s SEIU report concluded, “that the amount of state funding is not at issue in the failure to pay a living wage to direct care staff, but rather, that the root of the problem is the manner in which the providers have chosen to spend their increased revenues absent specific conditions attached to the funding.”

A look at the struggles of two families to cope with closures of sheltered workshops in Massachusetts

When Massachusetts closed its remaining sheltered workshops for people with developmental disabilities last summer, deeming the programs “segregated,” the impact of the closures on workshop participants Mark Garrity and Danny Morin was pretty much the same.

The two men continued to go every day to their respective facilities where their sheltered workshops had formerly been operated by providers funded by the Department of Developmental Services. But while the providers continued to manage the same facilities, each provider now began offering their clients traditional, DDS-funded day program activities instead.

Paid piecework and assembly work that had been given to Garrity and Morin to do in their sheltered workshops were taken away and replaced by day program activities that they couldn’t relate to. In each case, their provider agency managed to come up with a makeshift solution to the problem that allowed the men to continue doing work similar to what they had done before.

Patty Garrity and her brother, Mark Garrity

But in each case, the solutions were implemented despite a lack of clear, written standards or guidance from the federal and state governments on the type of work and activities that were now permitted for the men. Their family and guardians were confused as well, often having to rely on information passed along from program staff or family of other clients.

Even some providers acknowledge that the system functioned more smoothly for everyone when the providers were operating their programs as sheltered workshops. At that time, participating companies would ship materials to the providers, and everyone at the workshop sites would have work to do — usually simple assembly jobs or packaging or labeling tasks.

Now, those providers must either send their clients to companies that offer to provide “integrated” work for them, or must try to continue to provide some on-site work under unclear rules that sometimes result in work arrangements that are adopted verbally and on a case-by-case basis. Moreover, most of their clients are now offered only day program activities that do not involve productive work and do not pay anything.

For Barbara Govoni, the mother of Danny Morin, and for Patty Garrity, the sister of Mark Garrity, the sheltered workshops were not only easier for them to deal with, they provided meaningful and satisfying activities for their respective loved ones.

“My argument is whether it was federal or state, they should not have taken away the workshops for those who can’t function in the community and disrupted their lives,” Govoni said. “I’m not opposed to finding jobs in the community or expanding day programs. I get it all has to do with money, but I feel that a group of people are being discriminated against based on the fact they had no voice or vote. They have been taken out of their element where they were comfortable.”

Barbara Govoni and her son, Danny Morin

Govoni views the policy of providing integrated employment to all developmentally disabled people as a “misguided one-size-fits-all” approach to a complex social need.

State cites federal pressure to close workshops

All sheltered workshop programs were closed in Massachusetts as of last summer as a result of requirements by the federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) that developmentally disabled people work in “integrated employment” settings in which a majority of the workers are not disabled, and that they be paid the minimum wage in those settings. Sheltered workshops were deemed “segregated” settings because they were offered solely to groups of developmentally disabled persons, and the clients were often paid only a nominal amount for the work they did.

In Massachusetts, the Baker administration claimed it had no choice but to follow the CMS rules and close all of the workshops in the state, or else the federal government would bring a lawsuit against them. But many other states have apparently not acted in the haste that Massachusetts did in shutting the programs down. DDS Commissioner Elin Howe stated late last year that Massachusetts was one of the first states in the country to close all of its workshops.

DDS and its major policy advisors, the Arc of Massachusetts and the Association of Developmental Disabilities Providers (ADDP), had actually wanted to close all of the sheltered workshops in Massachusetts as early as June of 2015. But in the wake of strong protests by families of workshop participants, the state Legislature temporarily slowed the closure process by inserting budget language in fiscal years 2014 and 2015, stating that DDS must continue to make sheltered workshops available for those clients who continued to want them.

But at the same time, the Legislature approved funding for the transfer of the participants out of the workshops and into day programs or employment programs. That move ultimately allowed the workshops to close while enabling legislators to claim they had acted to save the programs.

The closures of the sheltered workshops in Massachusetts resulted in the removal from those programs of close to 2,000 participants, but those closures do not appear to have translated into a steady flow of people into integrated employment.

Verbal permission given for on-site work

At the Road to Responsibility day program site in Braintree, which Mark Garrity attends, I met in late March with Patty Garrity and with senior staff of the provider and DDS officials to discuss Mark’s experience in making the transition from his sheltered workshop to the new system.

Like Barbara Govoni, Patty Garrity said the transition from the sheltered workshop has been difficult. Before RTR ceased operating as a sheltered workshop, Mark did a range of activities there, including collating, packaging, and other production work.

For months, after the workshop was closed in September of 2016, Mark was frustrated and angry, Patty said. RTR provided day program activities for him, but, as Patty put it, they “went over his head.” He wasn’t interested in nature walks or painting or cooking. In particular, he didn’t understand the class on money management.

In addition to his intellectual disability, Mark Garrity had suffered a traumatic brain injury in 1995 after having been hit by a car. He underwent years of rehabilitation from that accident, which had nearly killed him.

In a letter written before Mark’s sheltered workshop program was ended, Mark’s neurologist, Dr. Douglas Katz, a member of the Department of Neurology at Boston Medical Center and a professor at the Boston University School of Medicine, stated that participating in the workshop had been “an important part of his (Mark’s) rehabilitation effort…and…his life before his injury. It is an activity that is highly rewarding for Mark. He looks forward to it on a daily basis.”

Katz added that, “I understand this program is …likely to close because of new rules passed by the CMS. I think this would be a big loss for my patient Mark. I would support efforts to maintain this structured workshop for Mark and others that benefit from this service.”

As of March 2 of this year, when I first talked to Patty, RTR still had no work for Mark to do that was similar to the work he had done prior to RTR’s changeover from a sheltered workshop to a day program site. But as of March 20, RTR officials said they had found paper shredding work for Mark for two out of the four hours a day that he attended the program.

The paper shredding arrangement at RTR was done after DDS southeast regional director Richard O’Meara determined that it would not violate the CMS rules. O’Meara said the permission he gave to RTR to offer paper shredding to Mark was purely verbal. There was nothing placed in writing about it.

Hearsay information on piecework eligibility requirement

In January 2016, Govoni said, the Agawam-based Work Opportunity Center, her son’s former sheltered workshop provider, temporarily operated day programs in a function room in a local church after having closed its sheltered workshop program. “I walked in there one day (the temporary day program site),” she said, “and it appeared chaotic, with no structured activities.”

All of the Work Opportunity Center’s clients are now back at the agency’s facility. Govoni’s son gets sent out occasionally to integrated work sites and has some piecework to do at the Work Opportunity site as well. But the work is intermittent. She said she has also heard that those who want to do piecework at the Work Opportunity location will have to take a class explaining what piecework involves.

However, once again, Govoni said she has received nothing in writing about the reported class. She heard about it “through the grapevine.”

In the meantime, Govoni’s son receives a schedule of activities every month at the Work Opportunity Center. “I’m not saying it’s bad,” Govoni said, “but it’s not what he is interested in.” She said many of the activities are educational, such as lectures on geography or cooking demonstrations. Volunteer work is available as well at a local homeless shelter, and residents are taken on walks to the local library and other locations. “Danny doesn’t want to do that,” she said. “He wants to work.”

Both Govoni and Patty Garrity said Danny and Mark respectively didn’t care about making the minimum wage, and would rather work at their day program sites than get sent out to jobs in the community.

Disagreement over client and family satisfaction

If, like Barbara Govoni and Patty Garrity, family members are confused or dissatisfied by the current situation, O’Meara said, they aren’t letting him know about it. O’Meara said that he and DDS Area Director Colleen Mulligan, who was also in attendance at the March 20 meeting at RTR, are generally the first people whom family members and guardians call when there are problems with DDS care.

“I haven’t gotten a lot of complaints (about the closures of the sheltered workshops in his region),” O’Meara said. “Generally, if people are not happy, we know about it. These issues are addressed through the ISP (Individual Support Plans). I haven’t had many calls.”

Mulligan added that if problems were occurring like the ones Garrity has described, “I’m not hearing about it.”

But Garrity and some other advocates believe there may be few complaints now because the vocal protests that did occur when the workshop closures were first announced largely died down when families and guardians saw that their protests were having little effect.

A debate over integrated employment

At RTR, Chris White, the agency’s chief executive officer, maintained that even if the CMS requirements have been difficult to comply with, the requirements make sense because he believes that “everyone is capable” of working at integrated employment sites.

White’s viewpoint is in line with an August 2010 DDS policy document that states that “it has now been clearly demonstrated that individuals who were previously considered unemployable in integrated community settings can work successfully.”

But Govoni and Garrity maintained that the ideological viewpoint that the workshops segregated their participants and that integrated employment is feasible for everyone does not apply in their cases. “My son couldn’t wait to go to work (at his former sheltered workshop),” Govoni said. “He was not discriminated against. It was not a sweatshop for him, but the opposite. He doesn’t thrive in integrated sites. He would much prefer staying at the workshop where he was more comfortable. He doesn’t care what he gets paid.”

Govoni said that efforts to place her son in integrated work settings often did not work. In one case, she said, Danny was not able to do the work fast enough to satisfy the employer, and was terminated from the job. The speed of his work did not matter in the sheltered workshop.

Moreover, Govoni and Garrity maintained that even if integrated employment arrangements were feasible for everyone, there are not enough such jobs available to fulfill the demand now that the sheltered workshops are no longer available.

White said there were about 109 clients at RTR who were involved in “integrated group employment” at various job sites. That number was expected to rise this spring to about 120, he said.

At the same time, some 200 clients remained in RTR’s day program. White maintained, however, that those clients were happy with the activities they were doing, and that some were “on a retirement track.”

But it may be an open question whether all or most former workshop clients are really happy in day programs, or whether they simply have no choice but to remain in them.

Even DDS Commissioner Elin Howe appears to acknowledge that the state and its providers have been unable to find mainstream workforce jobs for a significant number of former workshop participants. While Howe made public remarks last year that we believe painted an overly rosy picture of the integrated employment situation, she did acknowledge that “many people transitioned (from sheltered workshops) to Community Based Day Support programs,” although she did not say how many.

Meanwhile, the Legislature has slowed funding for the transition to integrated employment. In order to carry out the administration’s integrated employment policy, the Legislature initially increased funding of the community-based day program line item in the state budget, and created a new line item to fund the transfers from the sheltered workshops. The idea was to increase both day program and job development staffing and training.

The new sheltered workshop transfer budget line item was initially funded in Fiscal 2015 with $1 million. That amount was raised to $3 million in Fiscal 2016, and the governor proposed to boost it to $7.6 million in Fiscal 2017. But the House and the Senate did not go along with the governor’s plan. The Legislature level-funded the line item for Fiscal 2017. The line item was not included in the governor’s budget for Fiscal 2018.

We agree with Garrity and Govoni that the case has not been made that integrated employment is suitable for all people with developmental disabilities, and it is apparent that not enough integrated work opportunities even exist for all of those that could benefit from it.

We think the federal government needs to rethink its flawed ideology regarding sheltered workshops, particularly the questionable claim that they are discriminatory and segregate their participants. The experience of Mark Garrity and Danny Morin provide further evidence that that claim is untrue.

MassHealth audit casts doubt on claimed savings in privatizing state services

Last year, State Auditor Suzanne Bump approved a proposal to privatize mental health services in southeastern Massachusetts after the for-profit Massachusetts Behavioral Health Partnership (MBHP) claimed it could save $7 million in doing so.

The auditor’s review under the Pacheco Law required Bump’s office to compare the proposed costs of privatizing the services with continuing to carry them out with state employees in the Department of Mental Health.

In a report released yesterday, the auditor maintains that MassHealth, the state’s Medicaid administration agency, made questionable, improper, or duplicate payments to MBHP totaling $193 million between July 2010 and 2015. Those allegedly improper payments appear to have been made under the same contract with MBHP that served as the vehicle for privatizing the mental health services last year.

Under that umbrella contract, known as the Primary Care Clinician Plan, MassHealth paid MBHP more than $2.6 billion between 2010 and 2015.

Given the finding that MassHealth’s total payments to MBHP include $193 million in questionable, improper, or duplicate payments, it would seem it has just gotten harder to argue that privatization of human services has been a great deal for the state.

In fact, it seems possible that one of the reasons MBHP was able to offer bids from two providers for privatizing the mental health services that were $7 million lower than what the state employees could offer was that the company knew it could more than make the money back in duplicate payments from MassHealth.

A description of the MBHP billing arrangement by the state auditor paints a picture of the company as a middle-man between MassHealth and providers of actual services under the Primary Care Clinician Plan (PCCP) contract.

According to the audit, the Commonwealth pays MBHP a fixed monthly fee under the PCCP contract for each member enrolled in MBHP. MBHP then “recruits and oversees networks of third-party direct care providers who assume responsibility for providing a range of covered behavioral-health care.” MBHP subsequently “pays the providers using the monthly…premiums received from the Commonwealth.”

MBHP’s real role here appears to be as a pass-through of state funds. What MBHP really seems to add to the process is an apparently large layer of bureaucracy.

We have noted that MBHP is a politically connected company whose parent companies manage the behavioral health benefits of 70 percent of MassHealth members. In April 2015, Scott Taberner, previously the chief financial officer at MBHP, was named Chief of Behavioral Health and Supportive Care in MassHealth.

As we pointed out, Taberner was put in a position to manage the contract with the company he used to work for.

State employee unions, including the Service Employees International Local 509, the Massachusetts Nurses Association, and the American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees Council 93 did challenge Bump’s initial approval of the privatization arrangement with MBHP last year for the southeastern Massachusetts mental health services.

The unions maintained that the lower bids submitted for the privatization contract assumed major cuts in staffing at mental health facilities in southeastern Massachusetts, which would be likely to result in lower-quality services. They argued that the Pacheco Law requires that service quality not be affected.

The Pacheco Law requires a state agency seeking to privatize services to submit to the state auditor a comparison of a bid or bids from outside contractors with a bid from existing employees based on the cost of providing the services in-house “in the most cost-efficient manner.” If the state auditor concurs that the outside bidder’s proposed contract is less expensive and equal or better in quality than what existing employees have proposed, the privatization plan will be likely to be approved. If not, the auditor is likely to rule that the service must stay in-house.

In December, the state Supreme Judicial Court upheld Bump’s Pacheco Law review.

An SEIU official said to us yesterday the union is reviewing the auditor’s latest audit. We think that at the very least, the audit calls into question the savings claim in privatizing the southeastern Massachusetts mental health services.

More broadly, the audit of the MassHealth-MBHP contract calls into question MassHealth’s system of internal controls in managing state’s $13 billion Medicaid program.

It appears the MassHealth internal control system is so inadequate that the administration was unaware that hundreds of millions of dollars in improper payments were being made to its major contractor. Yet the administration was eager to reward MBHP’s efforts to eliminate state employees and cut staffing for mental health services in order to save a reported $7 million.

The MassHealth-MBHP debacle should serve as a warning to legislators and others that privatizing state services is not an automatic panacea to problems in service delivery and to high costs. Privatization comes with potentially high costs of its own, particularly when the state forsakes its role, as it appears to have done in this case, of adequately managing and overseeing its contracts with service providers.

Data show a recent decline in the developmentally disabled population in state-run residential care

Data provided by the Baker administration show that the number of residents in remaining state-run residential programs for the developmentally disabled has begun to decline, raising questions about the state’s policy for the future of state-run services.

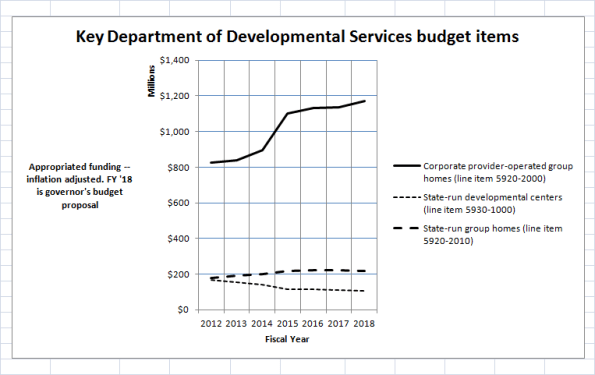

The data, which were provided under a Public Records Law request, indicate that the previous fiscal year (2016) may have been the peak year for the residential population in state-operated group homes and the Wrentham and Hogan developmental centers.

The graph below, which is based on the DDS data, shows the number of residents living in state-operated group homes each year since Fiscal Year 2008:

As we have frequently pointed out, the administration appears to have placed a priority on funding privatized residential services offered by corporate providers to the Department of Developmental Services. A question remains, however, as to whether the administration’s policy also entails phasing out state-operated care.

While Governor Baker’s Fiscal 2018 budget proposes $59.9 million in additional funding for privatized group homes, his budget proposes a $1.8 million cut in the state-operated group home account. That would amount to a $6.9 million cut in that account when adjusted for inflation.

Similarly, the governor is proposing a $2.4 million cut in the state-run developmental centers line item. That’s a $4.9 million cut when adjusted for inflation.

DDS operates or manages both state-run and privatized systems of residential care in Massachusetts. The state-run system, which is now much smaller than the privatized system, includes the two remaining developmental centers and the state-operated group homes.

The ultimate elimination of state-run residential services would take away a key element of choice for individuals and families in the DDS system. State-run residential centers and group homes provide residential care to some of the most profoundly disabled persons in the commonwealth, and they tend to employ staff with higher levels of training and lower rates of turnover than do corporate-run facilities.

COFAR has sent a follow-up Public Records request to DDS, seeking any policy documents that concern the future of state-operated care in Massachusetts.

The administration of then Governor Deval Patrick began closing the remaining developmental centers in Massachusetts in Fiscal 2008, reducing the number of those federally overseen facilities from six to two. Most of the residents in the now-closed developmental centers were transferred either to the Wrentham center or to state-operated group homes, leading to an initial surge in the residential populations in those facilities. But those residential population numbers now appear to be dropping.

According to the DDS data, the number of residents in state-operated group homes rose from just over 1,000 in 2008, when four of the six developmental centers were targeted for closure, to roughly 1,150 in Fiscal 2016. As of the current fiscal year, that number had dropped to about 1,130.

As the graph below shows, both a population surge and drop-off have also occurred at the Wrentham Developmental Center since Fiscal 2008:

The DDS data appear to provide further confirmation of COFAR’s contention that state-run residential facilities are not being offered as residential choices to persons waiting for residential care in the DDS system. We believe that if those facilities were routinely offered as choices, the number of residents in them would either continue to rise or remain steady, but would not be declining.

If DDS is failing to offer state-run group homes and developmental centers as options to people waiting for residential care, that situation would appear to be in violation of federal laws, which require that all available services be offered as options.

The Home and Community Based waiver of the Medicaid Law (42 U.S.C., Section 1396), requires that intellectually disabled individuals and their guardians be informed of the available “feasible alternatives” for care. In addition, the federal Rehabilitation Act (29 U.S.C., Section 794) states that no disabled person may be excluded or denied benefits from any program receiving federal funding.

We think the DDS data closely track the closures of the Fernald, Monson, and Glavin developmental centers, starting in Fiscal 2008, and the transfer of the residents of those facilities primarily to the state-operated group homes and the Wrentham center.

But as we reported in 2014, while 49 new state-operated group homes were built between 2008 and 2014, 28 state-operated homes were closed during that period. The new state-operated homes appear to have been intended to accommodate only the residents of the homes that were being closed and the residents transferred from the developmental centers.

Nevertheless, an undisclosed number of disabled individuals are reportedly waiting for residential services in Massachusetts, although the state does not maintain an official waiting list that would publicly identify the number of people waiting. The Massachusetts Developmental Disabilities Council has continued to cite a 2010 survey indicating that some 600 people were waiting for residential services in the state, and up to 3,000 people were waiting for family support services.

As noted, the administration appears to be attempting to meet the demand for residential care by boosting funding to corporate residential providers. While that hasn’t prevented the budgets of state-run developmental centers from increasing, those budgets may be leveling off.

The DDS data, which includes information about the Wrentham and Hogan developmental center budgets, shows increases in those budgets between Fiscal 2008 and 2015. Wrentham’s budget, in particular, appears to have leveled off, starting in Fiscal 2015.

It is unclear if or when the administration intends to phase out state-run DDS residential care, but the initial data are cause for concern. If you have a loved one in a state-run facility or are seeking care in a state-run setting, please let your local legislators know about this situation.

You can find your legislators at this link.

Harvard researcher looks for the key to understanding the link between Down syndrome and Alzheimer’s disease

The link between Down syndrome and Alzheimer’s disease has become the subject of increasing scientific interest, and a major new study is seeking to shed further light on that connection.

Dr. Florence Lai of Harvard University, McLean Hospital in Belmont, and Massachusetts General Hospital, is the lead Massachusetts investigator in a multi-center, five-year study funded by the National Institutes of Health.

Dr. Florence Lai

In an interview with COFAR, Dr. Lai said the study is seeking “biomarkers” that may predict the onset of Alzheimer’s disease and enable researchers to learn more about Down syndrome. It is intended to be “the most comprehensive study of the links between Down syndrome and Alzheimer’s disease up to this point.”

Lai and her colleagues, Dr. Diana Rosas, a neurologist, and Dr. Margaret Pulsifer, a psychologist, are in charge of the Massachusetts portion of the study.

While the average person with Down syndrome develops symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease in their early 50’s, some may not develop the dementia until the age of 70, and a very few escape it altogether.

“The study seeks, among other things, to learn the reasons for that variation,” Dr. Lai said.

The Massachusetts General Hospital’s facility at the Charlestown Navy Yard is one of seven sites around the country and England that are coordinating their research efforts as part of the study. The other sites include Columbia University (New York City), the University of California Irvine, the University of Pittsburgh, Cambridge University (UK), the University of Arizona (Phoenix), and the University of Wisconsin (Madison).

The NIH study represents a natural progression in Dr. Lai’s clinical practice and research. Over several decades, she has evaluated and followed some 750 individuals with Down syndrome, including Joanna Bezubka, a cousin of COFAR Board member and former president, George Mavridis. In 2013, Mavridis published a compelling memoir about his experience in caring for Joanna, who died of Alzheimer’s disease in 2012 at the age of 60.

George Mavridis and Joanna Bezubka on Joanna’s 60th birthday. Joanna, who had Down Syndrome, died in 2012 at the age of 60 of Alzheimer’s Disease. She had been one of Dr. Lai’s clinical patients.

In a recent letter to Mavridis, Lai said that her hunch that women with Down syndrome who developed menopause early were more likely to develop Alzheimer’s disease earlier, led to an earlier multi-year NIH study by a colleague who proved the hypothesis.

Another hunch of hers that immunological factors in Down syndrome might be involved in Alzheimer’s disease is now the subject of intense scientific interest with many researchers concentrating on neuro-inflammation as a causative factor.

Those avenues of inquiry “may pave the way to think outside the box for potential treatments for AD (Alzheimer’s disease),” Lai wrote to Mavridis.

In her interview with COFAR, Dr. Lai said scientists have discovered that people with Down syndrome are genetically predisposed to create large concentrations in their brains of amyloid protein, which is connected with destruction of brain cells in Alzheimer’s disease.

The gene for the precursor of amyloid protein is located on Chromosome 21. Since people with Down syndrome have an extra copy of Chromosome 21, Dr. Lai explained, they “make the amyloid earlier and more of it. That may be the reason for the high incidence of Alzheimer’s disease in people with Down syndrome.”

In order to learn more about the impact of the amyloid protein and other potential biomarkers of Alzheimer disease, the NIH study is designed to collect a broad range of information from the participants in the study, including information on their health history, cognitive functioning, immune and genetic factors, and daily living activities. The information is obtained from cognitive testing, from blood samples that are sent to specialized labs around the country, and from caregivers of the participants.

The study also includes an MRI brain scan of the subjects and an optional PET scan (Positron Emission Tomography), which involves the introduction of a small dose of radioactive material to examine the presence of amyloid protein in the brain. Another optional part of the study includes analyzing the cerebral spinal fluid obtained from a spinal tap.

The 3-year NIH study is limited to adults over the age of 40 with Down Syndrome at three of the sites (including Charlestown) and over age 25 at the other four sites. At the MGH Charlestown site, the study involves three cycles of visits with each cycle involving two to three visits of up to five hours each. The second and third cycles each take place 16 months after the previous cycle.

Although the study was initially funded in September 2015, it took about a year to “harmonize the procedures at all the sites,” Dr. Lai said, and to receive the necessary approvals from the participating institutions including the Research Review Committee of the Department of Developmental Services in the case of Massachusetts. Lai said the researchers at the seven study sites hope to recruit up to 700 individuals to participate in the study.

Lai said that although the NIH authorized the multi-million dollar study in 2015, the federal agency recently announced that it will be forced to cut some of the funding. She noted that the study is expensive to perform. A large number of specialized personnel is needed, and doing the brain scans is “very costly.”

At the MGH site, about 20 participants have been recruited so far and have been through a preliminary visit, Lai said. They receive a modest payment for their participation. The information collected is anonymous, she said. Even the researchers analyze only coded, aggregate data.

Continuing to treat Down Syndrome patients

Apart from the NIH study, Drs. Lai and Rosas continue to clinically treat, test, and follow the life histories of patients with Down syndrome at McLean hospital. They see each patient once a year and generate neurological evaluations which are shared with caregivers and family.

Lai has collected hundreds of blood samples, some of which have been stored at a Harvard-affiliated facility at -80 degrees C. However, the samples have lain dormant for many years due to a lack of funding needed to analyze them. Lai noted that many of her colleagues have experienced the same funding frustrations, and have had to supplement federal funding with industry grants and philanthropic donations.

It was actually due to the generosity of several families of her patients, Lai said, that she herself was able to start a Down Syndrome Fund for Alzheimer Research at MGH. The Fund got a boost of several thousand dollars a few years ago when a member of the MGH Board of Directors called Lai to thank her for her care of a patient with Down syndrome whom he knew personally.

Lai said that if the Down Syndrome Fund ever does get more sizeable contributions, her “dream” is to team up with colleagues to fully analyze the stored blood samples, and “to encourage a younger generation of clinicians and investigators to devote their energies to care for and study those with Down syndrome.”

Persons interested in learning more about the NIH study at MGH can call 617-726-9045 or 617-724-2227.

Those interested in an evaluation and follow-up with Drs. Lai and Rosas at the McLean Hospital Aging and Developmental Disabilities Clinic can call 617-855-2354.

Dental practitioner bills could undercut care of the developmentally disabled

Sometimes even well-intentioned bills in the Legislature can have unintended impacts, and we’re concerned about two such bills that authorize mid-level dental practitioners to perform basic dental procedures in order to address under-served populations around the state.

Versions of one of the bills are being promoted in several states, including Massachusetts, by the Pew Charitable Trusts. The second bill is being promoted by the Massachusetts Dental Society.

While we appreciate the intent behind the bills, we are concerned that passage of either one as currently written could actually result in the loss of existing services to clients of the Department of Developmental Services.

If either bill is enacted, many DDS clients, who are currently served by experienced dentists, could be switched by the administration to less skilled and experienced practitioners as a money-saving measure.

Backers of the Pew Trusts bill (S. 1169) point out that large numbers of adults and children in this and other states around the country are unable to access dental care either because they live in under-served areas or because only about a third of U.S. dentists accept publicly provided health insurance.

Under S. 1169, practitioners known as “dental therapists” would work under supervisory agreements with dentists, and would be authorized to do such things as fill cavities, extract teeth, and apply crowns. While this may work well for patients in the general population, we don’t think it is workable for many people with developmental disabilities who require dentists with advanced skills and significant experience.

As such, we would not support either S. 1169 or the competing bill from the Massachusetts Dental Society (S. 142) unless either bill contained language specifying that dentists must continue to treat persons with developmental disabilities.

The primary sponsors of S. 1169, Senator Harriette Chandler and Representative Smitty Pignatelli, maintain that hundreds of thousands of children covered by Masshealth in Massachusetts do not regularly see a dentist.

However, it has apparently not been as difficult to find a dentist for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities (ID/DD). Right now, the availability of dental services to persons with ID/DD appears to be quite high in Massachusetts. The Massachusetts Developmental Disabilities Council’s (MDDC) State Plan for Fiscal 2017 states that between 90% and 97% of DDS clients have continued to receive annual dental exams.

Some 7,000 developmentally disabled persons in Massachusetts receive dental care in seven state-funded clinics run by the Tufts University School of Dental Medicine. Pediatric dentistry is offered by Franciscan Hospital for Children.

Despite that high level of service provision, we have seen in the past that administrations have proposed elimination of some of the Tufts clinics in order to save money. Strong opposition from families of DDS clients helped to preserve at least one such clinic temporarily at the now closed Fernald Developmental Center, but that clinic was ultimately closed.

Our concern is that as currently written, either S. 1169 or S. 142 might actually give the Baker administration an excuse to reduce funding for the Tufts clinics because those clients could now presumably be served by the dental therapists or hygienists, as authorized by the legislation. If that is the case, there could be an increasing impetus to close additional Tufts facilities for those clients.

Moreover, while S. 1169 requires that the dental therapists receive training in treating people with ID/DD, the therapists would certainly not have the expertise or experience of the dentists in the Tufts clinics. The bill actually doesn’t specify the amount of training the dental therapists would be required to receive.

The Tufts Dental school declined to comment on either bill. Dentists themselves in Massachusetts oppose S. 1169, arguing that it does not provide for sufficient training of the dental therapists or direct supervision of them in all cases. The dentists also fear the use of dental therapists could lead to reduced reimbursement rates from insurance companies.

The Dental Society’s bill (S. 142) would establish more stringent educational and supervisory requirements regarding mid-level practitioners than does S. 1169. The Dental Society bill would require, for instance, that mid-level practitioners, which S. 142 refers to as public health dental practitioners, be under the direct, on-site supervision of a dentist at all times.

If either bill does pass, we would urge that language be added to prohibit the dental therapists or public health dental practitioners from having authorization to treat people with ID/DD unless an individual’s guardian specifically requested it.

We think that language along those lines would potentially protect existing dental services for people with ID/DD. Allowing guardians to request the therapists or public health dental practitioners would keep those options open if full dental services were not available for a developmentally disabled individual.

We emailed a Pew Charitable Trusts dental campaign officer on February 17 to express our concerns about the S. 1169, but have not as yet received a response from him.

Last week, I also contacted a legislative aide to Senator Chandler, who defended S. 1169, contending that it would would not result in reduced services to persons with ID/DD, but would “strengthen Tufts” and allow them to provide the same services at a “slightly lower cost.”

The aide said he would convey our concerns to Senator Chandler and would try to arrange for someone from Pew to get back to us with their response to our concerns. As noted, that hasn’t happened yet.

No one from Rep. Pignatelli’s office has yet responded to an email we sent early last week.

S. 1169, which currently has 30 co-sponsors from the House and Senate, has been referred to the Legislature’s Public Health Committee. Please call the Committee at (617) 722-1206 and urge them to insert language into the legislation to prevent dental therapists from treating people with developmental disabilities unless a guardian requests that. Or you can email the co-chairs of the Committee — Senator Jason Lewis ( Jason.Lewis@masenate.gov) and Representative Kate Hogan (Kate.Hogan@mahouse.gov).

The Massachusetts Dental Society’s bill (S. 142) has been referred to the Consumer Protection and Professional Licensure Committee. That bill should also be amended to include our protective language. Please call that Committee at(617) 722-1612. Or you can email the co-chairs — Senator Barbara L’Italien (barbara.l’italien@masenate.gov) and Representative Jennifer Benson (Jennifer.Benson@mahouse.gov).

DDS providers pushing Gov. Baker to phase out state-run care

The major lobbying organizations for corporate providers to the Department of Developmental Services appear to be pushing the Baker administration and the Legislature to privatize more and more state-run care.

And the administration and Legislature have so far appeared to be more than willing to accommodate the providers.

Governor Baker’s Fiscal Year 2018 budget, which he submitted to the Legislature last month, further widens a spending gap between privatized and state-run programs within the Department of Developmental Services. In doing so, it appears largely to satisfy budget requests from both the Arc of Massachusetts and the Association of Developmental Disabilities Providers (ADDP).

In fact, the increase proposed by the governor in funding for privatized group homes is $26 million more than the $20.7 million increase the Arc had sought. The ADDP may be a little disappointed only because that organization had asked for a $176 million increase in that account!

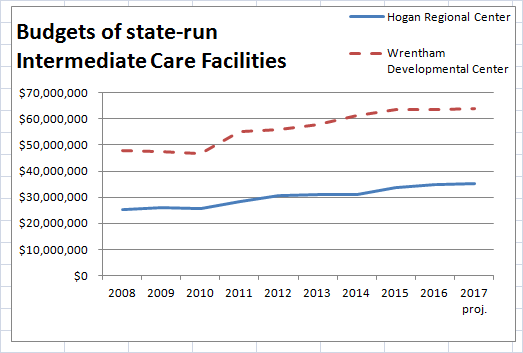

The chart below shows the widening gap in funding for key privatized and state-run DDS services over the past several years, adjusted for inflation. Under this trend, funding for corporate-run, residential group homes, in particular, has risen steeply while funding for state-operated group homes and developmental centers continues to be stagnant or cut.

For Fiscal 2018, the Arc requested a $20.7 million increase in funding for privatized group homes (line item 5920-2000), and the governor obliged with an even higher $59.9 million, or 5.4 percent, increase, as noted.* The ADDP, as noted, wanted a $176 million increase in that line item.

In the privatized community day line item (5920-2025, not shown on the chart), both the Arc and ADDP asked for a $40.2 million increase, and the governor responded with a proposed $13.6 million increase.

At the same time, both the Arc budget request for Fiscal 2018 and the ADDP request effectively asked for zero increases in funding for the state-run DDS accounts. Those include accounts funding state-operated group homes, developmental centers, and departmental service coordinators. (The column labeled “Request” in the linked Arc budget document is left blank for those state-run program line items. The ADDP budget request simply doesn’t include those line items.)

The governor appears to have more than obliged the provider organizations regarding those state-run accounts as well. His Fiscal 2018 budget proposes a $1.8 million cut in the state-operated group home account (5920-2010). This amounts to a $6.9 million cut when adjusted for inflation.

In addition, the governor is proposing a $2.4 million, or 2.2%, cut in the state-run developmental centers line item. (5930-1000). That’s a $4.9 million cut when adjusted for inflation.

And the governor is proposing a cut of $96,000 in the DDS administration account (5911-1003). That is a $1.7 million cut when adjusted for inflation, and means a likely cut in funding for critically important DDS service coordinators, whose salaries are funded under the administrative account.

It’s well known that the Arc and the ADDP oppose developmental centers because those two organizations oppose congregate care for the developmentally disabled and support only care in group homes or smaller settings. What may not be as well known is that the Arc and ADDP appear to have no interest in more funding for service coordinators or state-run group homes, in particular.

Late last month, Baker submitted his proposed Fiscal 2018 budget to the Legislature’s House Ways and Means Committee. In a letter to Representative Brian Dempsey, the chair of the budget panel, COFAR requested that, at the very least, the committee approve a plan to redirect some of the governor’s proposed increase in the corporate residential account to the state-operated group home, facilities, and service coordinator accounts.

(We would note that we have been urging this kind of redirection of funding for the past two years, and neither the governor’s office nor the Legislature are listening.)

Service coordinators

Service coordinators are DDS employees who help ensure that clients throughout the DDS system receive the services to which they are entitled under their care plans. In recent years, funding for service coordinator salaries has failed to keep up with their growing caseloads.

A reason for the Arc’s apparent disinterest in service coordinators may be that the organization has long promoted privatized “support brokers,” in which the Arc is financially invested.

The job descriptions of the Arc support brokers and the DDS service coordinators appear to be quite similar. The Arc notes on its website that “consumers or families hire a support broker to help them find appropriate services and supports to thrive in their community.”

The job description of DDS service coordinators states that they are responsible for “arranging and organizing DDS-funded and generic support services in response to individual’s needs.”

COFAR Executive Director Colleen M. Lutkevich terms the DDS service coordinators “the eyes and ears that make sure that the providers who report to DDS are doing their best for the residents in a large, confusing system. Without them, the provider agencies have total control, and families do not even have a phone number or a name to call outside the provider they are dealing with.”

Underfunding of state-operated group homes

In addition to provider-run group homes, DDS maintains a network of state-run group homes that are staffed by departmental employees. State workers receive better training on average than do workers in corporate provider-run residences, and have lower turnover and higher pay and benefits.

State-operated group homes provide a critically important alternative to the largely privatized residential care system that DDS oversees. But we have found that DDS routinely fails to offer state-operated homes as an option for people waiting for residential care, and instead directs those people only to openings in the privatized residences.

To be clear, we do not object to a highlight of Governor Baker’s budget — his proposed $16.7 million increase in the DDS Turning 22 account, which would amount to a 222% increase in that account over the current year appropriation. Turning 22 funds services for a growing number of developmentally disabled persons who leave special education programs at the age of 22 and become eligible for adult services from DDS. This account has been historically underfunded.

But our concern is that as they enter the DDS system, those 22-year-olds will be placed almost exclusively in privatized programs. An important choice is being taken away from them and their families.

As we noted in our letter to the House Ways and Means chair, the pattern of privatization in Massachusetts state government has become almost permanently established even though the benefits of privatization are highly debatable. Many questions have been raised about the privatization of prisons and the privatization of education in Massachusetts and elsewhere around the country.

The privatization of human services may be the biggest prize of all for government-funded contractors. We need to preserve what’s left of state-run services.

(*The $59.9 million figure for the governor’s proposed increase in the corporate provider line item is based on numbers provided by the nonpartisan Massachusetts Budget and Policy Center. The Arc’s budget document claims the governor’s requested increase was $46.7 million.)

Disability Law Center aids woman who has been kept away from father and sister by DDS

In the wake of reports that an intellectually disabled woman has been prohibited for more than a year by the Department of Developmental Services from having any contact with her father and sister, a federally funded legal assistance agency has arranged for legal representation to help the woman challenge the ban.

The Boston-based Disability Law Center opened an investigation late last year of a decision by a DDS-paid guardian to prohibit contact between the woman and her father, David Barr, and sister, Ashley Barr. Based on privacy concerns raised by the DLC, we are no longer publishing the woman’s name.

Earlier this month, a DLC attorney said the agency had assisted in making an attorney available at no charge to the woman to challenge the visitation ban in probate court, if she chooses to do so. The attorney said he was precluded by confidentiality requirements from discussing the investigation or any conclusions he may have reached in the case.

Since Thanksgiving of 2015, David and Ashley Barr have had no information about the woman’s whereabouts. She is believed to be living in a DDS-funded group home, but the Barrs have no idea where that residence might be located.

COFAR has reported that a DDS guardian imposed the ban on all contact with the woman by David and Ashley primarily because they were viewed as too emotional when they were allowed to visit her. Neither David nor Ashley Barr have been charged or implicated in any crimes, yet they said they feel they have been treated by DDS as if they are criminals.

In COFAR’s view, restricting family members from visiting a loved one impinges on a fundamental human right, and the DDS guardian should at least have obtained a probate court order before doing so. DDS should also have made sure the woman had access to legal counsel who could challenge the visitation ban on her behalf. DDS reportedly did neither of those things.

The case appears to involve a clear violation of DDS regulations, which state that people in the Department’s care have the right …“to be visited and to visit others under circumstances that are conducive to friendships and relationships…” (115 CMR 5.04)

The right to visitation is, moreover, a key aspect of family integrity in international human rights law. As an article in the Berkeley Journal of International Law states, “Sufficient consensus exists against particular types of family separation…to constitute customary international law.”

The article discusses Nicholson v. Williams, a class action lawsuit by a group of mothers against the New York City Administration for Child Services (ACS). The lawsuit “challenged ACS’s policy of automatically removing children from homes where domestic violence had occurred even if it meant removing them from the victims rather than the perpetrators of that violence.”

The children of the plaintiffs in Nicholson were kept in foster care for several weeks. According to the law journal, the court “cited the emotional and developmental damage done to the children, (and) the destruction of their family relationships…” that occurred as a result of the separation of the children from their parents (my emphasis).

We would note that the ACS lawsuit was a case involving the removal of children for just a few weeks. The Barr case involves the removal of a family member for more than a year so far, with no indication from DDS that family contact will ever be restored.

While the developmentally disabled woman in Barr case is no longer a child, she has been found to be mentally incapacitated and in need of a guardian. As such, she is in a similar legal position to a child in that she is not considered competent to manage her personal or financial affairs.

The court in Nicholson v. Williams cited specific international provisions including the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and found that the New York ACS policy “violated the basic human rights of family integrity and freedom from arbitrary interference with family life, as well as the specific right of a child to be cared for by her parents.”

In what seems almost an obvious observation, but one that doesn’t seem to have occurred to DDS, the Berkeley law journal article notes:

People simply care a great deal about their families, and often suffer more from losing them than they do even from serious individual harms they suffer personally.

A couple of other points made in the law journal article are worth highlighting. One is a statement that temporary removal of children from families may cause “lasting harm to the children…especially if frequent visitation is not allowed during the removal period.”

The article also points out that the International Convention on the Rights of the Child (ICRC) imposes obligations on states in situations where families have already been separated. In particular, the ICRC states that where children are separated from one or both parents “the state must furnish the parents or children with any available information regarding their family members’ whereabouts” (my emphasis).

The Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court weighed in last spring with a decision upholding the right of the grandfather of a developmentally disabled woman to challenge severe restrictions placed on his right to visit her.

As we’ve said before, and will again, major reforms are needed in the state’s probate court system in order to ensure the rights of families to maintain contact with their loved ones in DDS care. One of the first steps is for the Legislature to finally pass a bill (filed in the current session as HD 101) that would require probate judges to presume parents to be suitable guardians for persons with developmental disabilities.

DDS commissioner paints overly rosy picture of employment for developmentally disabled

In opening remarks at a conference on employment opportunities for the developmentally disabled late last year, Department of Developmental Services Commissioner Elin Howe gave what appears to be an overly rosy assessment of the likelihood of mainstream jobs for those people.

In her written remarks delivered to the November 30 conference, which was hosted by DDS and the UMass Institute for Community Inclusion, Howe appeared to imply that former participants in sheltered workshops, which the administration has worked to close, have been placed in mainstream jobs at a record rate.

“There are now more people working in individual jobs in the community than ever before,” Howe stated.

But while the numbers Howe cited show an increase in the number of people placed in mainstream jobs since 2013, it appears that most of that increase occurred between 2013 and 2014, before the workshop closures took place. Since 2014, DDS data indicates that the number of people finding mainstream jobs declined rapidly.

Howe noted that all remaining sheltered workshops in the state were closed as of last July 1, and that Massachusetts was only the fourth state in the nation to do that. But the loss of those workshops should not be a cause for concern, Howe contended, because, there were now more than 3,300 individuals working in “group supported employment” in the state – an increase of over 1,300 people since June 2013.

An increase of 1,300 disabled people in group supported employment would work out to a 65 percent increase in the number of people in that category since 2013, which sounds like a major success story.

But of that total increase cited by Howe of 1,300 individuals, 998 — or nearly 77 percent of them — appear to have entered group supported employment between 2013 and 2014, according to data provided by DDS.

The DDS numbers show there was an increase of only 146 people in group supported employment between August 2014 and August 2015. Between August 2015 and November 2016, when all remaining sheltered workshops were closed, there was an increase of only 156 people in group supported employment.

So, while the number of people in group supported employment appears to have increased by almost 50 percent between 2013 and 2014, the increase in the two-year period from 2014 to 2016 dropped to about 10 percent.

Group supported employment is defined by DDS as “a small group of individuals, (typically 2 to 8), working in the community under the supervision of a provider agency.” In contrast to sheltered workshops, supported employment places an “emphasis…on work in an integrated environment,” which means that developmentally disabled persons work in the same location as non-disabled individuals.

The closures of the sheltered workshops in Massachusetts has resulted in the removal from those programs of close to 2,000 participants since 2013; but those closures did not appear to have translated into a steady flow of people into supported employment. Even Howe appears to acknowledge that a significant percentage of those former workshop participants have not found mainstream workforce jobs.

In her remarks, Howe stated that “many people transitioned (from sheltered workshops) to Community Based Day Support programs,” but didn’t say how many. Day programs are often really just daycare programs that do not offer work-based or skill-building activities to the people in them.

The Massachusetts Developmental Disabilities Council, which is part of the Baker administration, appears to acknowledge the problem of employment in its State Plan for 2016, noting that:

…there are fewer people being placed in successful employment due to staff layoffs and the current fiscal environment. In order for more services to be made available, it is important to create partnerships and work with various state agencies in order to address this significant issue that is and will continue to be of concern. (my emphasis)

Last year, however, the Legislature failed to provide funding sought by Governor Baker for the transition from workshops to supported employment.

Rather than touting the supposed good news about the closures of the workshops, Howe should have acknowledged ongoing concerns about the apparent difficulty of finding mainstream work for people with developmental disabilities.

Opaque Massachusetts budget process hides state’s real priorities

In a preview this week of the Fiscal 2018 state budget, the Massachusetts Budget and Policy Center points out a key shortcoming in the budget process.

That process is not transparent, the nonpartisan think tank argues, because it doesn’t provide a needed context for the proposals and decisions that the governor and Legislature make.

As the Budget and Policy Center notes, that needed context lies in the release of a public “maintenance budget” that discloses the projected costs of continuing “current services” from one fiscal year to the next. Without that “maintenance budget” context, it is difficult, if not impossible, for the public to really know whether proposed funding levels are meeting real needs or falling short of them.

The problem can be clearly seen in the current-year funding of group homes operated by the Department of Developmental Services.

Last January, Governor Baker proposed a $3.7 million — or 1.7 percent — increase in the DDS state-operated group home line item. But while that sounds like more funding for those facilities, it was in actuality a cut when adjusted for inflation. The inflation rate was 1.8 percent, according to the Policy Center’s numbers.

Moreover, the funding increase proposed by the governor for the state-operated group homes was reportedly about $500,000 less than what DDS wanted in order to maintain current services in the residences. That $500,000 figure, however, wasn’t readily available to the public. The figure was casually mentioned by DDS Commissioner Elin Howe during a conference call on the budget last year with advocates for the developmentally disabled.

At the same time, Howe didn’t intend to do anything about that actual shortfall in funding for the state-operated group homes. As we noted last May, while Howe admitted the funding proposed by the governor for the group homes was inadequate, she also said DDS did not intend to seek an amendment in the House budget to increase that funding. Howe’s response to us was, “we’re just going to have to manage it.”

This is exactly why the maintenance budget disclosure is needed as part of the process. It would give the public a better insight into what the governor and Legislature actually intend with their budget proposals and deliberations.

It appears to us that the DDS mindset is that it is not worthwhile to push even for maintenance-level funding for the state-operated group homes and potentially other state-run programs. That’s because the Department’s ultimate priority or aim, as we see it, is to privatize these services.

Interestingly, the Budget and Policy Center also pointed out that certain other budgetary accounts were underfunded in the current fiscal year, including a human services account that helps fund corporate provider-run or privatized group homes in the DDS system. That account was underfunded by $14.7 million. However, the administration apparently plans to fully fund those accounts next year, the Center noted.

Partly as a result of the unfunded accounts and the use of a host of one-time revenues and temporary solutions to balance the current-year budget, the Policy Center is projecting a $616 million budget shortfall in Fiscal 2018.

The Policy Center’s preview suggested that one of the major reasons for the Legislature’s underfunding of the privatized group home and other accounts was the lack of a publicly available maintenance budget document. The Policy Center points out that 19 other states publish a maintenance budget document, but Massachusetts is not among them.

The Policy Center is also calling for the public release of a baseline tax revenue growth estimate. This sounds like a suggestion that the administration adjust its usual revenue projections to take into account any tax cuts or tax increases that have been enacted. As the Policy Center noted,

The initial tax revenue growth estimates for FY 2017 were unusually optimistic, but there was no easy way to see that because of the way the estimates were presented.

We concur with the Budget and Policy Center’s recommendations, particularly on the need for disclosure of a maintenance budget. The more information the public has with which to assess the budgetary process, the better off we are, and this appears to be a key piece of missing information.