Archive

Public Health Department needs to release report on death of developmentally disabled man

The Department of Public Health has completed an investigation of the case of a developmentally disabled man who died en route to Lowell General Hospital in February 2012 after having been turned away from the hospital twice without any significant treatment.

We may never know, however, what the result of the investigation is. The Department, citing the deceased man’s privacy rights, won’t release the report.

We are appealing this denial to the state’s Public Records Division, arguing that the potential public interest in knowing what happened in this case outweighs the privacy rights of a deceased individual. Our view is that the real potential wrong to this person was done when he was denied treatment by the hospital. The public, we think, deserves to know what happened here and so do persons with developmental disabilities and their families and guardians.

This case suggests possible inadequate training of health care personnel in the treatment of developmentally disabled persons, which is an issue of concern to advocates for the disabled and to many policymakers.

The National Council on Disability, with which we have had our disagreements, maintains that:

The absence of professional training…for health care practitioners is one of the most significant barriers preventing people with disabilities from receiving appropriate and effective health care.

The man was a former resident of the Fernald Developmental Center. He had been living in a group home in Chelmsford and was attending a day program in Lowell on the morning of February 6, 2012, when the staff at the day program made the first call to 911 to take him to the hospital. He had reportedly been having difficulty breathing and was sweating profusely. The hospital released the man shortly after his arrival, however, and sent him back to his group home, according to sources.

By about 8 a.m. the following morning, the man was slumped over in his wheelchair and sweating heavily, a source said. A group home staff member called 911 shortly afterward.

A Disabled Persons Protection Commission (DPPC) complaint form stated that the man was observed at the hospital on the morning of February 7 to be sweating profusely, but his vital signs were good when he arrived. According to the complaint form, the man was sent home with a prescription (the name of which was redacted). According to sources, this was the second time he had been sent away by the hospital.

The DPPC complaint form stated that shortly after arriving back at the group home, the man began to vomit and then lost consciousness, and that the staff began mouth-to-mouth CPR until paramedics arrived. The group home received a call from the hospital later that afternoon that the man had died.

Because the man’s death appeared to have been connected with his treatment or lack of treatment by the hospital, the DPPC referred the case to the Department of Public Health for investigation.

Did the apparent failure of Lowell General Hospital to properly diagnose this man’s illness and provide him with adequate treatment result from a lack of training in disability issues? Did the Public Health Department consider that question in their investigation of this case? Unless the Department releases its report, we will never know the answers to those questions.

While the Public Health Department’s position is that a state law [(M.G.L. c. 66A, s. 2(k)] prohibits them from releasing medical information about an individual, even if that person is deceased, we are not in agreement with their interpretation.

First, there do not appear to be consistent policies among state agencies in releasing investigative reports on deaths of developmentally disabled persons. The Disabled Persons Protection Commission (DPPC) has released a number of these reports to us after redacting what they considered to be identifying information.

Secondly, while we have blogged about this case, we have never used the name of the individual involved or tried to publicly identify him. A Department of Public Health attorney wrote to us, though, that even if we did not use the individual’s name in a blog post about the investigative report, “it is possible for someone to utilize the information that is available (age and date of death) and potentially come up with the patient’s name.” While that is possible, we do not understand why anyone would do that in this case. It seems farfetched.

Third, even if it were true that someone might reveal the identity of the individual involved, there appears to be case law that limits privacy rights of deceased individuals. A Hofstra Law Review article notes that “while postmortem medical confidentiality exists, it is much narrower than the privacy protections guaranteed to the living.” In Massachusetts, case law involving privacy rights after death does not appear to have been settled. (See Ajemian v. Yahoo!, Inc.)

Finally, the privacy statute cited by the Public Health Department [(M.G.L. c. 66A, s. 2(k)] states only that the Department must:

maintain procedures to ensure that no personal data are made available in response to a demand for data made by means of compulsory legal process, unless the data subject has been notified of such demand in reasonable time that he may seek to have the process quashed.

This seems to imply that the person involved has to be living. And, as attorney Steve Sheehy notes in a comment to this post below, at most this statute would require notice to the deceased person’s executor or representative.

Prior to filing our appeal, I asked the Public Health Department attorney whether it might be possible to provide us with a copy of the investigative report with explicit personal data or medical information redacted. As I noted, our interest is whether the Department has investigated or commented on the hospital’s procedures for training staff to treat persons with developmental disabilities.

To the extent that the Department’s report addresses hospital policies and procedures in this case, it would probably not be necessarily for us to know specific medical details about this individual. To date, I have not received an answer from the Department to my query.

Unfortunately, this is not an isolated case of apparent institutional secrecy. When it comes to deciding whether to make public reports of potential mismanagement by human services or health care facilities, the natural instinct of public managers and administrators seems to be to keep it all secret and cite privacy rights as the reason. That has certainly been the practice at the DPPC, but at least, as noted, the DPPC has released redacted reports.

We hope the Public Records Division, which is part of the office of Secretary of the Commonwealth Bill Galvin, will make the right decision and order the Public Health Department to make known the results of its investigation of this troubling Lowell General Hospital case.

Compensation of provider executives in MA reaches $100 million

More than 600 executives employed by corporate human service providers in Massachusetts received some $100 million per year in salaries and other compensation, according to our updated survey of the providers’ nonprofit federal tax forms.

By our calculations, state taxpayers are on the hook each year for up to $85 million of that total compensation.

We reviewed the federal tax forms for some 300 state-funded, corporate providers, most of which provide residential and day services to persons with developmental disabilities.

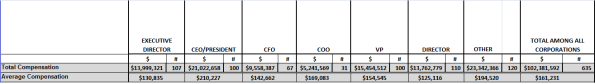

The following is a summary chart of our latest survey results (click on the chart to enlarge):

For the complete survey chart, click here.

We first released our survey about a year ago, when we found that more than 550 executives working for some 250 state-funded corporate providers of services to people with developmental disabilities in Massachusetts received a total of $80.5 million in annual compensation.

COFAR has also previously raised concerns that increasing amounts of money going to provider executives have not translated into higher pay for direct-care workers in Massachusetts.

The latest survey reports on 635 executives who received total annual compensation of $102.4 million and average annual compensation per employee of $161,231. The survey was based on provider tax forms filed in either the 2011 or 2012 tax years. Those tax forms are available online at www.guidestar.org.

The survey sample included 100 CEO’s and presidents, making an average of $210,227 in salaries and benefits; and 107 executive directors receiving an average of $130,835 in compensation. As the chart above shows, the survey also included 67 chief financial officers, 31 chief operating officers, 100 vice presidents, 110 directors, and 120 other officers, all earning, on average, over $100,000 a year.

A state regulation limits state payments to provider executives to $158,101, as of fiscal year 2013. Money earned by executives above the state cap is supposed to come from sources other than state funds.

Based on this regulation, we calculated that provider executives are eligible for up to $85 million a year in state funding to cover those total salary and benefits costs. Our calculation was based on identifying the companies paying executives at or above the state threshold of $158,101, and assuming that amount as the maximum state payment for each of those companies’ executives.

Among the top-paying providers in our latest survey was the May Institute, which paid two employees a total of $999,221 in the 2012 tax year. Both employees were listed as president and CEO of the provider. The May Institute’s federal tax form shows that one of the two employees, Walter Christian, worked for the company until December 2012 and received a total of $725,674 in salary and benefits in that tax year, which started on July 1, 2012. Christian was replaced as president and CEO by Lauren Solotar, who received a total of $273,547 in that same tax year, which ended on June 30, 2013.

Despite the regulation capping compensation payments by the state, the state auditor reported in May 2013 that the state had improperly reimbursed the May Institute, a corporate provider to the Department of Developmental Services, for hundreds of thousands of dollars paid to company executives in excess of that cap. COFAR had previously reported in 2011 that the state may have paid Christian and other executives of the May Institute more than the state’s regulatory limit on individual executive salaries.

The following charts show the top earning presidents/CEO’s and executive directors in our latest survey and the number of those executives holding each title in each company:

Most of the providers surveyed are under contract to the Department of Developmental Services, which manages or provides services to people with intellectual disabilities who are over the age of 22. The providers operate group homes and provide day programs, transportation and other services to tens of thousands of intellectually disabled persons in the DDS system.

As we have noted, the state’s priority has been to boost funding dramatically to corporate residential providers, in particular, while at the same time slowly starving state-operated care, including state-run group homes and developmental centers, of revenue.

Funding to DDS corporate residential providers rose past the $1 billion mark for the first time in the current fiscal year. The line item was increased by more than $140 million –or more than 16 percent—over prior-year spending in fiscal 2015 dollars. At the same time, both the former governor’s and the legislative budgets either cut or provided much more meager increases for most other DDS line items.

More financial information about nonprofit corporate providers, including compensation of executives, can be found at www.guidestar.org.

It’s time to put a priority on state-operated care for the developmentally disabled

Here’s our letter to the Baker administration, asking them to put a priority on state-operated care for the developmentally disabled:

Kristen Lepore

Secretary

Executive Office of Administration and Finance

State House, Room 373

Boston MA, 02133 January 12, 2015

Dear Secretary Lepore:

We are writing to urge you to consider making the funding of state-operated care for the developmentally disabled a priority of the Baker administration.

For too long, state government has been divesting itself of its responsibility to provide care for the most vulnerable of its citizens, and has failed to adequately monitor and control the handover of human services to state-funded corporate providers.

The state’s priority has been to boost funding dramatically to corporate residential providers, in particular, while at the same time slowly starving state-operated care, including state-run group homes and developmental centers, of revenue. This has led to a gross imbalance in the Department of Developmental Services budget. The chart below depicts this imbalance.

As the chart shows, funding to DDS corporate residential providers (line item 5920-2000) rose past the $1 billion mark for the first time in the current fiscal year. The line item was increased by more than $140 million –or more than 16 percent—over prior-year spending in FY 2015 dollars. At the same time, both the former governor’s and the legislative budgets either cut or provided much more meager increases for most other DDS line items.

The state-run developmental center line item (5930-1000) was cut in the current fiscal year by more than 13 percent in inflation-adjusted dollars, while the state-operated group home line item (5920-2010) was raised by less than 7 percent.

We have calculated that if the increase in the provider residential line item had been reduced by just 2.1 percent – to a 14.7 percent increase – as much as $18 million could have been redirected to the state-operated group homes, DDS service coordinators, the Autism Division, Turning 22 program, Respite and Family Supports, and the remaining developmental centers in the state.

But the previous administration was not satisfied even with a $140 million increase in funding for the corporate provider line item. In late November, despite a projected $329 million budget deficit in the current fiscal year, the Patrick administration proposed a supplemental budget increase of $42 million in the provider residential line item. While the administration made more than $200 million in emergency “9C” cuts and proposed additional cuts to address the projected deficit, it included the $42 million in proposed supplemental funding for the DDS corporate residential line item in the same bill (H. 4536) proposing mid-year cuts in local aid and other accounts.

In addition to the erosion of critical state-funded care, the state’s priority of boosting funding to corporate providers has created a poorly monitored system of DDS contractors that has financially benefited provider executives. Our own survey of the DDS provider system has shown that the state has provided between $80 million and $90 million a year to a bureaucratic layer of corporate CEO’s, vice presidents, executive directors, and other executives. At the same time, wages of direct-care workers in provider residences have been flat or have declined in recent years.

State-operated group homes and developmental centers

We believe the misplaced priority on funding of corporate providers ignores the wishes of family members and guardians around the state for more choice and availability in state-operated care. DDS data show that close to 42 percent of the 372 individuals moved out of developmental centers in the state since 2008 were placed in state-operated group homes. Another 45 percent of those residents were transferred, at the request of their families, to remaining developmental centers. Just 13 percent of those individuals went to provider-run group homes.

Yet, since 2008, 157 new provider-operated group homes have been built in the state, according to information provided by DDS. In that time, only 38 new state-operated group homes have been built, and three have been closed or converted to provider-operated homes. DDS has projected that it will build an additional six state-operated group homes, but will close or convert five state-operated facilities to provider residences.

Additional funding is needed for the state-operated group home system to preserve it as a choice for people waiting for residential care in the DDS system.

State-operated developmental centers

As a result of class-action lawsuits dating back to the 1970’s, the State of Massachusetts dramatically improved care in its state-run developmental centers, bringing them to a world-class level of care with dedicated, highly-trained staff. But starting in 2003, the Romney administration and subsequently the Patrick administration began efforts to close the state’s then six remaining developmental centers.

Starting in 2008, the Patrick administration stepped up the closure efforts and shut the Monson, Glavin, Templeton, and Fernald Developmental Centers, in many cases over the strong objections of families and advocates of the residents there. And despite the demonstrated desire of families and guardians for the intensive and high-quality care that the developmental centers provide to the most profoundly developmentally disabled, the developmental center line item has been cut repeatedly since 2008. The current-year DDS budget cut the developmental center line item by more than 13 percent in the current fiscal year alone, as noted.

We hope the Baker administration will consider restoring balance to DDS budget accounts by increasing funding to the developmental center and state-operated group home line items. State-operated care continues to be better monitored than provider operated care; and training as well as pay and benefits provided to staff in state-run facilities continue to be higher than in provider-run residences.

Ultimately, only government is in a position to respond directly to the public interest and to the wishes of families and guardians of the most vulnerable people among us. Federal law recognizes that fact by designating families as the “primary decision makers” in the care of individuals with developmental disabilities [(42 U.S.C. §2001(c)(3)].

Thank you for your consideration.

Sincerely,

Colleen M. Lutkevich Thomas J. Frain, Esq. Edward Orzechowski

Executive Director President President, Advocacy Network

Administration proposing last-minute regs changes that will reduce DDS oversight of providers

As it winds down to its last few weeks, the Patrick administration is set to make changes to two state regulations that we are concerned will reduce state oversight of corporate providers of services to the developmentally disabled and further reduce family involvement and choice in care and services.

We are particularly concerned about a proposed change by the Department of Developmental Services that appears to give DDS providers at least partial say in whether their licenses to operate residential and other programs are renewed. Proposed new language in the regulation (115 CMR 8.00, Certification, Licensing and Support) codifies a process that allows providers to assess their own compliance with state licensing and certification standards. This, to us, seems to sanction a conflict of interest.

Meanwhile, proposed changes to a second regulation (115 CMR 7.00: Standards for All Services and Supports) appear to reduce staffing requirements for group homes and remove the words “rights and dignity” from a discussion about providing residential supports and services to DDS clients. More about those additional changes below.

The rewrite of the licensure regulation adds a new section that refers to both a “self-assessment” done by the provider of its own supports and services and a “targeted review” of the provider by the Department as part of the licensure renewal process. Licenses to operate are normally granted to DDS corporate providers every two years following a survey or inspection of their residences and programs. The following sentence in this new section seems to describe a key aspect of this process:

Ratings from the targeted review and self-assessment [done by both the Department and the provider] will be combined to determine…the licensure levels for the provider. (my emphasis)

Based on this language, it appears as though the provider is expected to be involved in making the decision whether the provider will be granted a full renewal of its license or a conditional license or whether it will receive some other licensure requirement. This seems to defeat the purpose of the licensure process, which should be to provide an outside assessment of the provider’s ability to provide adequate supports and services, and to make licensure decisions that are independent of influence from the entity being licensed.

In particular, the provider will be given the authority to review licensure and certification “indicators” that it was found in surveys not to have met.

DDS licenses and certifies hundreds of nonprofit, state-funded group home and day program providers throughout the state each year. A review by COFAR in 2012 of 30 randomly selected online licensure and certification reports raised a number of questions about the effectiveness of the provider licensure and certification system in general. The review also found that DDS made substantial changes to its licensure and certification procedures based on input from the providers themselves.

Other proposed licensing changes

In addition to the introduction of the self-assessment process, the rewritten licensure regulation adds a requirement that the Department give providers at least 30 days notice of planned licensure visits or surveys of their residences. Currently, there is an advance notification requirement, but there is no timetable for that notice in the regulation. Under the new language, the provider has a month to get ready. Once again, this allowance appears to defeat the purpose of the licensure survey process, which is to assess the ongoing care and conditions in facilities.

If a provider knows a month ahead of time exactly when a two-year licensing survey of its facilities will take place, the provider will have an incentive to bring its facilities into compliance with licensing standards at that particular time, but not necessarily at any other time.

In the same section, the rewrite removes current language stating that notification of the survey must also be given to guardians, family members, individuals, and service coordinators. It seems doubly inappropriate to us that the providers will receive a month’s advance notice of planned survey visits, but guardians and families will apparently no longer be told about those visits. We cannot think of any legitimate justification for eliminating that notification to families and guardians other than a desire to keep them in the dark about the Department’s licensure and provider monitoring efforts.

In addition t0 those changes:

- The rewrite of the licensure regulation removes a statement that the survey team may review the provider’s system for conducting Criminal Offender Record Information (CORI) checks on all persons whose paid responsibilities may bring them into direct contact with individuals served. We do not understand the rationale for removing this common-sense requirement.

- The rewrite removes language stating that in cases in which a provider fails to correct conditions that place residents’ lives in jeopardy, those services will not be licensed or certified until such time as corrective action has been taken. We do not understand the rationale for removing this common-sense requirement either.

- The rewrite also increases the length of term of a “conditional license” granted when there is only “partial achievement” of licensing standards or “critical indicators” from one year to two years. Thus, even if a provider is only able to partially meet licensing standards, the provider will still receive the same two-year term for its license as providers that are able to meet all the standards.

Changes to the Services and Supports regulation

As noted above, DDS is proposing a number of changes to the services and supports regulation, which we are concerned will reduce both group home staffing requirements and rights of DDS clients. Those proposed changes include the following:

- In defining and discussing both Residential and Individualized Home Supports, the rewritten language in this regulation removes the words “rights and dignity” in discussing client outcomes. In one instance, that wording is replaced by language stating that providers “shall operate in a manner that supports positive outcomes for individuals in all of the services and supports offered…”

- In defining Family Supports, the rewrite eliminates the phrase that these supports should “enable the family to stay together.” We cannot think of any legitimate justification for removing that phrase.

- In discussing Staffing Standards, the rewrite removes a reference to providers having sufficient staff with enough training to ensure “quality of life outcomes delineated in the provider’s mission statement…”

- The rewrite of this same section removes a requirement that there be at least two staff persons on duty in homes where three or four individuals live and in which three or more individuals require assistance to evacuate within 2½ minutes. In addition, the rewrite removes a requirement that at least one “overnight awake” staff person be on duty at night in homes in which at least one individual requires assistance to evacuate within 2 1/2 minutes.

- The rewrite adds a section to the regulation that appears to advocate the opportunity of “integrated” or mainstream work opportunities for all persons with developmental disabilities, apparently no matter how low-functioning they are. For instance, the new language states the following: “Integrated, individual employment is the preferred service option and outcome for adults of working age…All individuals are to be encouraged and supported in seeking and securing employment or becoming engaged on a pathway to employment.” (my emphasis)

We believe the Department needs to recognize that there are differences in the levels of ability and achievement potential in different people. The new language in this section reflects an ideological blindness to those differences and does a disservice to all persons with developmental disabilities.

DDS has scheduled hearings on the regulatory changes on Wednesday (December 17) at 10 a.m. at the DDS Central Office at 500 Harrison Avenue in Boston, and on Thursday (the 18th) at 10 a.m. in the Northborough Free Library, 34 Main Street, Northborough. Written comments may be submitted by mail to the Office of the General Counsel, DDS Central Office, or by fax to (617) 624-7573 until 5:00 p.m. on Thursday.

We thought there was a state budget deficit

Given that the Patrick administration is projecting a $329 million state budget deficit in the current fiscal year and is seeking to cut millions of dollars in local aid and other accounts, why are they also proposing more than $42 million in additional funding in the current year for corporate providers that contract with the Department of Developmental Services?

While the administration has made more than $200 million in emergency “9C” cuts and has proposed additional cuts, it has filed a supplemental budget appropriation to add $42.5 million to the DDS Adult Long-term Residential (corporate provider) line item. The supplemental funding for the providers, by the way, is listed in the same bill filed by the administration that proposes mid-year cuts in local aid and other accounts.

It’s not as though DDS itself is being spared the funding cuts. As part of the 9C reductions, two DDS line items are being cut: the Community Day and Work line item by $3 million, and Respite Family Supports by $2.5 million.

But the DDS providers are getting multiple funding increases. As of July 1, the administration and Legislature had agreed to raise the provider line item by $159 million from the previous fiscal year, pushing it over the $1 billion mark. The reason for that nearly 20 percent increase in funding in one year was to fully fund higher payment rates to the providers that were agreed to in legislation enacted in 2008 and known as “Chapter 257.”

But even that $159 million increase this year wasn’t apparently enough. The $42.5 million supplemental appropriation now being sought by the administration is supposedly to make up for a continuing shortfall in fully implementing the Chapter 257 rate increases for the providers.

But why make up that Chapter 257 shortfall now while we’re facing a state budget deficit? Chapter 257 has apparently not been fully funded since it was enacted in 2008, so why is it so important to commit $42 million to it now?

Meanwhile, in light of the planned $42 million increase to the providers, the decision to cut at least one of the two DDS programs –Respite Family Supports by $2.5 million — is especially puzzling. Respite care involves short-term, out-of-home supports for individuals with developmental disabilities who live at home. It allows parents and other primary caregivers to handle personal matters, emergencies, or simply take a break. In fact, DDS listed its commitment to supporting families who care at home for developmentally disabled individuals as the third of its top five strategic goals for fiscal 2012 through 2014.

The DDS strategic plan goes on to promise that:

The Family Support account will provide the resources needed to provide vital respite care, in-home skills development, social programs and support groups for parents and siblings.

The administration and Legislature had, in fact, approved a $2.5 million — or roughly 5 percent — increase in the Respite Family Supports account as of the start of the fiscal year on July 1. So taking that increase away now amounts to an effective cut in inflation-adjusted terms in this “vital” program. The fact that the money is being rescinded in the middle of the year effectively doubles the impact of that cut to $5 million on an annualized basis.

The DDS Community Day line item had been increased by $11.8 million from the previous fiscal year, apparently in part to help fund the transfers of people from sheltered workshops to day programs. In addition, the Legislature had approved two reserve funds totaling $3 million to help fund that same transfer from sheltered workshops to day and employment programs.

The mid-year cut in the Community Day account of that same $3 million amount may make some sense given that language was approved in the current-year budget preventing the planned closures of sheltered workshops. If the workshops are going to stay open past this coming June, DDS won’t need the funding they were originally projecting to transfer people to day programs.

But while the Community Day account cut might make some sense, the cut to the Respite Family account seems to make much less sense. And when considered in light of the extra millions going to the providers, the Respite Family cut seems downright cruel.

In fact, we might take this occasion to ask what happened to the additional $80 to $110 million in Medicaid funding from the federal government that was going to be used to “increase community services and decrease institutional settings in Massachusetts?” As the Massachusetts Association of Developmental Disabilities Providers stated, “the activities of DDS comprise a significant part of the base for this (additional Medicaid) award…”

If we have received up to $110 million in additional Medicaid funding this year, why not use that to help solve the budget deficit, and at least prevent cuts to critical programs such as Respite Family care? Moreover, we hope the House and Senate Ways and Means Committees will see fit to put the administration’s proposed $42 million increase in state funding to the DDS providers on hold, at least while we’re dealing with the current budget shortfall.

DDS should not be investigating itself for abuse and neglect in the Perry case, or in any other cases

As Fox 25 news reported earlier this month, the Department of Developmental Services has determined there was not sufficient evidence to charge staff at the Templeton Developmental Center with mistreatment, stemming from the death last year of Dennis Perry, an intellectually disabled man.

Perry, who was 64, died in September 2013 after having been allegedly shoved into the side of a boiler at the developmental center’s dairy barn by Anthony Remillard, a resident of the center, who had a history of violent behavior.

The DDS investigation report and related correspondence, dated in August of this year, termed the behavior of certain staff prior to the alleged assault “inappropriate” and “unprofessional,” and recommended retraining of Templeton personnel. But the report concluded that there wasn’t evidence that the staff could have prevented Remillard’s alleged “spontaneous and unpredictable assault” on Perry.

We are not in a position to second-guess the conclusions of the DDS report. But this case once again raises the question whether it is appropriate for DDS, in effect, to investigate itself in abuse and neglect cases.

Due to legal loopholes, which I’ll discuss below, DDS itself investigates all cases of abuse and neglect of persons over 60 with developmental disabilities who live in long-term care facilities operated or contracted by the Department. As a result, the Department’s investigation of Perry case and its handling of it raise numerous questions.

By way of disclosure, Thomas Frain, president of COFAR’s Board, is representing Perry’s family in legal action against the state in the incident. I haven’t consulted Attorney Frain in writing this post, other than to ask him for a copy of the DDS investigation report.

Among the questions raised by the Perry case that don’t appear to have been considered in the DDS report are: Was it appropriate for Remillard to have been admitted to the Templeton Center in the first place, and was the overall level of supervision at the Templeton Center adequate? The DDS report didn’t even appear to consider whether the level of supervision of Remillard himself was adequate. The report merely examined the actions of staff caring for Remillard in the moments prior to, and during, the alleged assault.

For instance, the DDS report noted that a Templeton staff member had “sat” on Remillard because he wouldn’t get up from a nap just before the alleged assault of Perry occurred, and told him he would not be given a sandwich if he didn’t cooperate. There was a reference to a staff person “flicking” some water at Remillard as well.

The DDS report, which was based on statements taken from staff, stated that Remillard laughed in response to the staff person’s actions, got up and went to a bathroom to change his shoes. Then, on his way with a staff member to the an exit door in the dairy barn, Remillard suddenly spun around and shoved Perry, who had been standing nearby, toward the boiler, causing him to hit his head and fall to the floor. The staff stated that Remillard’s action was so unexpected and sudden that there was nothing they could do to prevent it.

That may all be perfectly true, but in focusing entirely on the actions of staff immediately prior to the alleged assault, the DDS report missed the potentially more important questions noted above. The report did note that Remillard had a history of criminal assaults and threats, including threatening with a dangerous weapon and threatening to blow up a school, and had a pending arson charge against him when he was admitted to Templeton. While at Templeton, he was verbally abusive toward staff and had assaulted staff members, according to the report. So, why not examine some questions that go beyond just what the staff at the time of the alleged assault did or didn’t do?

As we have pointed out many times, Templeton is one of several state-run facilities that have been either closed or significantly downsized in recent years, and the declining level of staffing and supervision in these facilities has been a source of concern. It’s not surprising that DDS, which is heavily invested in closing and downsizing these facilities, would not want to examine any potential negative impacts of that downsizing.

For reasons like that, we have long argued in favor of providing more funding and resources to the Disabled Persons Protection Commission (DPPC), an independent agency, to investigate abuse and neglect complaints. The DPPC, however, has been given such a limited budget and resources by the administration and Legislature that it is forced to refer most of the complaints it receives to DDS for investigation. The DPPC is further prevented by statute from investigating allegations of abuse or neglect of individuals over the age of 60.

Because Perry was over 60, the DPPC referred the investigation of his assault to both DDS and the Executive Office of Elder Affairs, according to a DPPC official whom I emailed about the case. The EOEA itself is prohibited by statute, however, from investigating abuse cases involving elderly persons in long-term care facilities such as developmental centers and group homes.

The result is that DDS has become, by default, the only agency with authority to investigate cases such as that of Perry in which an elderly person with an intellectual disability is allegedly abused in a long-term care facility.

The DPPC tried to rectify that situation as long ago as 1992. A May 1994 directive from the then secretary of elder affairs expressed support for a bill filed that year by the DPPC that would have allowed the DPPC to investigate reports of abuse of elderly persons living in facilities operated or contracted by DDS. The directive noted that similar legislation had failed to pass in the previous two years. The 1994 bill wasn’t enacted.

A DPPC official said this week that the agency filed a bill again in 2000 that would have given it the authority to investigate abuse of elders in DDS facilities. That bill failed as well, and the agency hasn’t tried again since. It seems fairly clear that the DPPC realized it was going to get nowhere with legislation that would give it more investigatory authority at the expense of DDS.

For years, the DPPC has asked for more resources to enable it to hire more investigative personnel. In our view, it has been DDS itself that has lobbied the Legislature against the DPPC’s common-sense recommendations to increase its investigative authority and resources, and has fought to keep the DPPC’s budget as low as possible. It appears to be a political turf issue as far as DDS is concerned.

In the meantime, it appeared earlier this year that the Legislature’s Children, Families, and Persons with Disabilities Committee might step in and take an independent look at the Perry case and the issues surrounding it. Last January, we received a notice from the office of Representative Kay Khan, House chair of the committee, that the committee was planning an oversight hearing on the Perry case. But despite a subsequent inquiry that we made to the committee, we never received any additional information about such a hearing.

On Monday, I emailed both Khan and her staff, and Senator Michael Barrett, committee Senate chair, and his staff, asking whether an oversight hearing on the Perry case is still planned and, if not, why it had been cancelled. To date, I’ve received no response to those queries.

When Big Brother (thinks he) knows best about the developmentally disabled

It can be frustrating when government administrators take it upon themselves to tell citizens what is in their best interest, and that includes telling them what is in the best interest of their family members with developmental disabilities.

It’s particularly frustrating when the state and federal governments tell people that they know best where their family members should or should not live.

For instance, the folks at the federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) have determined that farm-based residential programs are not good for developmentally disabled people. Also bad are residential schools for the developmentally disabled, group homes on the grounds of a private developmental or Intermediate Care Facility (ICF), and group homes located in “close proximity” to each other.

Both CMS and the Massachusetts Department of Developmental Services have decided that all of those types of residential settings “isolate” the participants from the “broader community.” But while the feds are not banning those particular settings outright, the state DDS, in a new policy, appears to be proposing to do just that. According to the DDS policy, residents of “noncompliant programs” will be given “the opportunity to move to a compliant setting” or else face possible dis-enrollment from the HCBS program.

It doesn’t appear to matter that the participants may greatly enjoy living on a farm, for instance, or that they may derive many important skills from farm programs that improve their self-care, receptive and expressive language, learning, mobility, self-direction, and capacity for independent living. It doesn’t matter either that their families and guardians may value those skills highly and consequently value those programs themselves.

It also doesn’t appear to matter that thousands of people in Massachusetts are waiting for residential and other care options, and that eliminating potential options, as CMS and DDS are doing, is only going to make that situation worse.

CMS issued a new regulation earlier this year that states that the residential settings they have identified as isolating may not qualify for Medicaid funding that is specifically earmarked for “home and community-based services.” In “guidance” provided on the regulation, CMS criticized residential farm programs, in particular, because “an individual generally does not leave the farm to access HCBS (Home and Community Based Services) or participate in community activities.” CMS said similar things in the guidance document about residential schools for people with developmental disabilities, and about other programs that “provide multiple types of services and activities on-site.”

In its new policy based on the CMS regulation, DDS states that it will not fund or support new residential settings such as farmsteads, “gated or secured communities,” residential schools, settings that “congregate a large number of people with disabilities for significant shared programming and staff,” or even new group homes with more than five residents.

DDS has scheduled public forums on its policy and a “transition plan” to comply with the CMS regulation on November 6 at 6 p.m. at Massachusetts Bay Community College in Wellesley, and November 12 at 10:30 a.m. at Westfield State University in Westfield.

It is not clear what evidence CMS has to make the claims that people in farm-based and other congregate care programs are not provided with access to community activities. The federal agency’s guidance offers no citations or backup information or studies to support its claims.

Moreover, even if it were true that on most residential farms and in other programs providing “multiple services” that the residents are not regularly taken into the community, wouldn’t it make more sense to require that those programs periodically take participants into the community than to effectively ban the programs altogether? Isn’t that throwing the baby out with the bath water? CMS acknowledged that it received many comments about how valuable and therapeutic those farm programs, in particular, are.

By the same token, CMS appears to be ignoring evidence that there is often little or no community integration by residents of small group homes. Yet, even CMS isn’t willing to prohibit Medicaid funding for farm programs, residential schools, or multiple group home settings outright. In contrast to the Massachusetts DDS, CMS has stated that it will subject so-called isolating programs to “heightened scrutiny,” which may result in continuing to fund them if a state makes the case that the settings do not have institutional qualities.

CMS, in fact, specifically rejected the idea of banning group homes with more than a set number of residents. In responses posted on the Federal Register to public comments on the proposed regulation, CMS stated that it had previously proposed defining institutional care based on the number of residents living in a facility, but that:

…we were persuaded by public comments that this was not a useful or appropriate way to differentiate between institutional and home and community-based care. As a result, we have now determined not to include or exclude specific kinds of facilities from qualifying as HCBS (home and community based services) settings based on the number of residents in that facility (my emphasis).

CMS also noted on the same Federal Register site that the goal of its new Medicaid regulation:

… is not to take services from individuals, or make individuals move from a location where they have always lived… The goal of this regulation is to widen the door of opportunity for individuals receiving Medicaid HCBS… to have a choice in how, when, and where they receive services; and to remove unnecessary barriers and controls. (My emphasis).

So CMS states that its goal is to give people choices and NOT to make people move from a location where they have always lived; but the Massachusetts DDS has made it their goal since the Patrick administration came into office to move people away from where they’ve always lived. It’s evident from the language of the DDS policy and from DDS’s own actions over the past several years that the choices of individuals and their families and guardians do not signify here. For instance, only corporate provider-run settings are routinely offered by DDS as options for people seeking residential care.

Yet while the Massachusetts DDS is going beyond what CMS apparently intended in moving to eliminate available options for residential care, CMS has given the states the latitude to do so. As Tamie Hopp of the VOR, a national advocacy organization for the developmentally disabled, noted, states have “incredible discretion in terms of how they operate their Medicaid programs.”

In a publication, VOR contends that the new CMS regulation “continues to demonstrate an ideological bias against disabled people who find friendships and benefits from living together and accessing services and amenities ‘under one roof.'” VOR further suggests that:

…if CMS determines some settings to be too ‘institutional’… it is likely that states will realize higher costs to accommodate transitions to likely smaller, scattered settings where economies of scale will not be realized. Quality of care and access to specialized services may also be affected, exacting an untold cost on affected individuals.

For some, this is really all about cutting Medicaid programs and diverting Medicaid funding to corporate providers, who are being encouraged to operate more and more widely dispersed, and smaller, group homes. The corporate providers in Massachusetts are apparently fine with all of this. In fact, DDS notes in its transition plan that it consulted with “a small stakeholder group (including providers, advocates and participants/family members).” The usual advisors to DDS are listed in the transition plan, including the Arc of Massachusetts and The Association of Developmental Disability Providers (ADDP).

It may just be that the people who are truly isolated in institutions are the folks working at CMS and the Massachusetts DDS, who appear to have little idea of how things work in the real world. Someone needs free them from their ivory towers!

You can help by sending your comments on DDS’s policy to their email address at HCBSWaivers@MassMail.State.MA.US. You can also write to: HCBS Waiver Unit, 1 Ashburton Place, 11th Floor, Boston, MA 02108. Comments must be submitted by November 15.

Why we won’t be at the bill signing at Fenway Park

Tomorrow, Governor Patrick will be at Fenway Park for the ceremonial signing of three pieces of legislation that are intended to make major changes in the care and services for the developmentally disabled in Massachusetts.

Many advocates will be there, but many if not most of those in attendance will be corporate providers to the Department of Developmental Services, who played key lobbying roles in the drafting of each piece of legislation last spring. As a result, as we have pointed out, each of these new laws (because Patrick signed them for real in August) is flawed in a major way.

There really is no reason to celebrate unless and until changes are made in the laws, so we won’t be at the event tomorrow. In a nutshell, here are the problems with the laws:

1. National Background Check law: The law authorizes national criminal background checks for persons hired to work in an unsupervised capacity with persons with developmental disabilities. It will ultimately require that both current and prospective caregivers in the DDS system submit their fingerprints to a federal database maintained by the FBI. Those requirements are long overdue, but they will be further delayed under the new law.

The fingerprint requirements will not be phased in under the law for all current employees in the system until January 2019, and will not take effect for new employees until January 2016. Another provision in the new law that raises questions appears to allow employees to be hired before the results of their background checks are obtained.

COFAR and the VOR, a national advocacy group for the developmentally disabled, sent a joint message to lawmakers this week that states: “Much harm can be done to vulnerable people due to the delayed implementation and the ambiguous language that we hope was not the intent of the Legislature.”

When COFAR contacted the Legislature’s Judiciary Committee last summer to ask why the committee had approved the delays and the ambiguous provision in the new law’s requirements, a staff member referred us to Johnston Associates, a Beacon Hill lobbying firm. A member of the firm said providers and some other advocates had pushed for the delays. No one could or would give us an answer as to why language was inserted that appears to allow the hiring of employees before their background checks are done.

2. The ‘Real Lives’ law: This legislation had been pushed for years on Beacon Hill by the providers. The stated intent of the measure is to introduce “person-centered planning” into the DDS care system by allowing each DDS client to “direct the decision-making process” and manage their own “individual budgets” for care.

In the wake of criticism earlier this year from COFAR, legislators removed a provision from the bill, which would have named the Association of Developmental Disabilities Providers and the Arc of Massachusetts to a board that would advise DDS in developing the person-centered planning system. Another provision that was thankfully removed would have established a “contingency fund” to compensate providers that lose funding when clients move out of their residential facilities.

But the new law still raises a number of concerns, including providing what appears to be only a limited role for guardians and family members in the person-centered planning process. The law also introduces a central role in the process for vaguely defined “financial management services” and other privately run entities.

In a joint statement this week, the VOR and COFAR called on legislators to “ensure that vulnerable individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities have the support of legal guardians, when appointed, rather than financial managers or independent facilitators” in undertaking person-centered planning.

The joint statement also urged legislators to add a provision to the law ensuring that persons seeking DDS services would have an explicit choice among a range of care options and settings, including state-operated facilities and group homes, provider-operated homes, shared living arrangements, and home-based care. State-operated care is often not presented as an option to people seeking DDS residential services. Those persons are instead presented only with the option of corporate provider-operated residential care.

3. The DDS eligibility expansion law: This legislation is intended to fill a major gap in DDS care in Massachusetts by extending eligibility for services to people with autism and two other specified disabilities known as Prader-Willi Syndrome and Smith-Magenis Syndrome.

Until the enactment of this law, DDS had restricted eligibility for DDS services to people with “intellectual disabilities,” as measured by a score of approximately 70 or below on an IQ test. That left out many people with developmental disabilities, including autism, even though those conditions may severely restrict an individual’s ability to function successfully in society. If those people score higher than 70 on an IQ test, they are routinely denied services.

However, in specifying three developmental disabilities that make individuals eligible for DDS services, the new law necessarily leaves out other conditions that often result in many of the same types of functional limitations, such as Williams Syndrome, spina bifida, and cerebral palsy. The new law was the product of closed-door negotiations among legislators, administration officials, and selected advocacy organizations.

In addition to changing that eligibility standard, the new law establishes a permanent new autism commission and authorizes the establishment of tax-free, individual savings accounts to pay for a variety of DDS and other services. The commission will consist of 35 members, including legislators, administration officials, the Arc of Massachusetts, and advocates from autism advocacy organizations. There are no seats on the commission for any advocates of state-run care for the developmentally disabled.

The VOR and COFAR urged legislators this week to make changes in the law “to better identify and serve eligible individuals in need of services and supports.”

In sum, while these new laws have many well-intentioned supporters, major changes are needed in each piece of legislation to enable it to fulfill its purpose and prevent it from doing more harm than good. It is not yet time for everyone to pat themselves on the back as will no doubt be happening tomorrow at Fenway Park.

Heavily redacted state reports raise more questions than answers in sudden deaths of DDS clients

More than three years after the sudden death of a former resident of the Templeton Developmental Center, we have received a report on the matter from the state Disabled Persons Protection Commission, which found that the resident had adequate care and services at the time of his death and that there was no evidence he had been neglected or abused.

But the report is so heavily redacted that it is difficult to determine whether a number of specific questions and allegations that had been raised about the person’s care were actually investigated. It is also unclear why it took nearly two years for the DPPC to provide us with the report, which was completed and approved by a supervisor in the agency in November 2012.

The former Templeton Center resident died on July 24, 2011, four days after he was transferred to a state-operated group home in Tewksbury. The cause of death was reportedly a blood clot in his lung.

This was one of three cases we heard about in 2011 and 2012 in which clients of the Department of Developmental Services, each of whom happened to be a man in his 50’s, died suddenly after being transferred from developmental centers to state-run group homes operated by Northeast Residential Services, a division of DDS. A second case was that of a former resident of the Fernald Developmental Center, who died on July 6, 2011, after having ingested a plastic bag in a Northeast Residential Services group home in which he was living in Tyngsborough.

In that second case, a DPPC report concluded that there was a lack of adequate supervision of the man by his caregivers, although the investigative agency was unable to determine whether the man had ingested the plastic bag while he was in the group home or his day program or was being transported between the two. That report was also so heavily redacted that it left numerous questions about the incident unanswered for us, including whether the man’s care plan may have been significantly changed after he left the Fernald Center.

In a third case, a 51-year-old resident of a Northeast Residential Services home in Chelmsford died of acute respiratory failure on February 7, 2012, after having been sent back to his residence twice by Lowell General Hospital. That man had formerly lived at the Fernald Center as well. We have just requested that report from the DPPC.

While it is of course disturbing that three DDS clients would die suddenly in a relatively short span of time in the same regional group home system, we have no information to indicate that staff in any of the Northeast Residential Services homes were at fault in any of the deaths. These cases may in fact raise more questions about the DPPC’s investigation and reporting procedures than they do about care in DDS-run group homes.

In the case of the man who died of a blood clot four days after leaving Templeton, we raised questions at the time whether the stress of the move may have contributed to his death, or whether there was a medication error or other care issue involved. It was also unclear whether staff familiar to the man while he was at Templeton was available to accompany him to his new residence in Tewksbury. Moreover, we noted that DDS may not have had uniform policies or procedures in place as to whether familiar staff should accompany transferred residents to their new locations.

The DPPC report found that the man had direct-care staff available 24 hours a day and nursing staff “as needed” in his group home, and that there was no evidence that any medication error had occurred.

I have written to the DPPC to ask why it took so long to release the report on the former Templeton resident’s death. I had requested a copy of the report by letter on October 31, 2011. The report is dated as having been completed on November 1, 2012, and as having been approved by a DPPC supervisor that same day. It was mailed to us with a cover letter, dated September 17, 2014.

In contrast, the report on the July 2011 death of the former Fernald resident who ingested the plastic bag, while also heavily redacted, was dated March 29, 2012, and provided to us in May of 2012.

The former Templeton resident’s guardian, who was also his niece, told me after his death in July 2011 that her uncle had had a blood clot in his leg about a year before the move from Templeton (deep venous thrombosis), but the problem had been cleared up. She said he had been put on a blood thinner called Coumadin, but that she later found out that he was taken off that medication while he was still at Templeton. She said she was never consulted about the decision to take him off the medication. The guardian said that other than the instance of thrombosis, her uncle had only minor health problems. He had worked every day in the dairy barn at Templeton.

While most of the discussion in the DPPC report on the issue of the former Templeton resident’s medication appears to have been redacted, there was a statement in the report that “all necessary medications were continued,” and that a review of documentation from July 19 through the day of his death on July 24, 2011, “indicates no medication error occurred.” Due to the redactions, however, it could not be determined from the report which medications the DPPC considered to be necessary. There was no mention in the unredacted portions of the report of any allegation that the Coumadin had been discontinued.

The guardian had also told me the staff from the group home had spent about a week at Templeton with her uncle prior to the move, but she was not sure whether any familiar staff from Templeton accompanied him during the actual transfer to the new residence. The unredacted portions of the DPPC report were not clear concerning this potential allegation either.

According to the DPPC report, the man’s move from Templeton to the Northeast Residential group home had been planned, and staff from both facilities attended the planning meetings. The resident was actively involved in choosing the new residence and visited it along with familiar staff and family prior to moving there, the report stated.

In discussing the circumstances of the man’s death, the DPPC report stated that he had left his bedroom at 9:15 on the morning of July 24, 2011, and had indicated he was not feeling well. Three staff members responded immediately. The man became short of breath and then unresponsive, so CPR was initiated immediately and 911 was called. CPR was continued until the arrival of paramedics, who continued it while the man was transported to a hospital by ambulance. He was pronounced dead at 9:47 a.m.

The March 29 DPPC report on the death of the man who ingested the plastic bag also leaves many questions unanswered about his care, including whether the man’s Individual Support Plan (ISP) had been changed in a significant way after he left the Fernald Center, and whether his level of supervision in the group home was less than the level he had received while at Fernald. There is an indication in the report that the man’s ISP was changed in September 2010, apparently after he moved to the group home, to remove “target (presumably inedible) items” from mention in the plan. Much of this discussion, however, was redacted in the report.

The man reportedly had a history of ingesting foreign objects, a condition known as pica. However, even what was apparently the word “pica” was redacted throughout the report.

It is understandable that public health and human service agencies have a desire to protect the privacy of individuals in their care or their jurisdiction. But it often seems that the desire to redact or withhold information goes much farther than necessary and fails to protect the public’s right to know about these cases. In our view, the two DPPC reports discussed here fall into that latter category. We believe much of the redacted information in both cases could have been made public without compromising either of these individuals’ privacy in any way.

The questions raised about the care and services that were investigated in these cases are important ones. Something seems to be wrong when investigative and other agencies withhold key facts about cases like these and end up being the only ones who know those facts.

DDS policy will disperse people and care

A new Patrick administration policy statement on care and services for people with developmental disabilities states that its intention is to enable people to lead “fully integrated lives” in the community.

But the statement, which was issued on September 2 by the Department of Developmental Services, would appear to take us further down a path of dispersal and isolation of people in the DDS system.

Among other provisions, the policy states that DDS will limit the number of people living in new group homes to five or fewer. Individuals who continue to live in “non-compliant” residences could be dis-enrolled from the Department’s Medicaid-funded programs, the policy states.

In setting the five-person limit, the policy goes even further than a new Obama administration regulation on Medicaid-funded, community-based care on which the state policy is supposedly based. The Massachusetts policy even bans new programs that provide farm-based residential care to people with developmental disabilities, and further appears to ban new residential programs that provide recreation or other programs to groups of disabled people.

All of those programs and services are apparently too “institutional” for the Patrick administration, which apparently believes that any setting that serves more than five disabled people automatically “isolates them from the broader community.”

Massachusetts DDS Commissioner Elin Howe signed the policy, which states that it is based on the new federal rule issued by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), which sets new standards for providing Medicaid funding to community-based providers. But while the Massachusetts policy is supposedly based on the CMS rule, the CMS specifically rejected a proposal to specify the number of people who are allowed to live in community-based facilities.

In responses to comments about its proposed rules, the CMS stated that while they initially proposed a limit on the number of people who can live in group homes and still qualify for Medicaid funding, they were persuaded by public comments that “this was not a useful or appropriate way to differentiate between institutional and home and community based care.”

The DDS policy is not as draconian as that of the highly ideological National Council on Disability, which has determined that any facility housing four or more people is “institutional” in nature and should be shut down. Nevertheless, one has to ask why the Patrick administration would set a limit on the number of people who can live in new group homes when even the federal administration, which strongly favors community-based care, has determined that such a limit is not useful or appropriate.

As was the case with sheltered workshops, the Patrick administration has shown itself to be more ideologically opposed to state-run and congregate care than the federal government. It seems to us DDS’s policies on sheltered workshops and community-based care will only further disperse people and services, and ironically, further isolate them. While advocates of deinstitutionalization have long argued that community-based care is intended to reduce isolation, the opposite appears to be occurring.

Other troubling aspects of the new DDS policy on community-based care stem from its statement that DDS will not license, fund or support new residential settings with “characteristics that isolate individuals from the broader community.” That’s fine in itself, but the policy goes on to say that those isolating characteristics are to be found in:

- “Settings that have limited, if any, interaction with the broader community.”

But what does limited interaction mean and who judges it? The policy doesn’t define this. In fact, we often hear complaints from family members and guardians that small group homes provide for virtually no interaction with the broader community. In this sense, we have always considered that larger, congregate facilities provide more of a sense of community, almost by definition, than do many group homes.

- “Settings that use or authorize restrictions that are used in institutional settings.”

What restrictions? The policy gives no further information on this.

- “Farmsteads or disability-specific farm community (sic).”

Why the ban on farmsteads? Farm-based programs have been found to be highly conducive to treatment and well-being of developmentally disabled individuals. Last year, I wrote a post on the SAGE Foundation blogsite about three successful farm-based programs, each of which provides a range of treatment, crafts, and other programs and services to people with either developmental disabilities or mental illness. Many of these farm programs were founded by parents frustrated by the lack of services available to people with autism, in particular.

- “Gated or secured communities for people with disabilities.”

The DDS policy provides no further information on this.

- “Settings that are part of or adjacent to a residential school.”

This provision is a troublesome aspect as well of the CMS rule. How does being adjacent to a residential school somehow makes a residential setting institutional?

- “Multiple settings co-located and operationally-related that congregate a large number of people with disabilities for significant shared programming and staff.”

This appears to limit many potentially effective programs and ideas. I’ve written about two of these ideas to develop residential services and programs for a larger number of people in both community and developmental-center settings. Given the large number of people waiting for care and services in Massachusetts and other states, it makes sense to consider these proposals.

DDS should be looking, as noted, at ways to serve people who are waiting for care. As the Massachusetts Developmental Disabilities Council pointed out in its 2014 state plan, Massachusetts is lagging behind other states in funding and providing care and services for people with developmental disabilities.

The Developmental Disabilities Council described “limited options due to a lack of adequate resources” for adults entering the DDS system. In light of all of that, we fail to understand why the Patrick administration has issued a policy that will only further limit options available to people with developmental disabilities.