Archive

Committee airs testimony on sexual abuse of the disabled, but offers little indication of its next steps

While members of a legislative committee heard testimony on Tuesday about sexual abuse of the developmentally disabled in Massachusetts, the state lawmakers on the committee gave little indication as to what they plan to do with the information.

COFAR was one of several organizations invited by the Children, Families, and Persons with Disabilities Committee to testify. The committee members asked no questions of any of the three members of COFAR’s panel, who testified about serious and, in one case, fatal abuse of their family members in Department of Developmental Services-funded group homes.

Tuesday’s hearing on sexual abuse in the DDS system. The committee members asked no questions of COFAR’s panel.

COFAR President Thomas Frain, Vice President Anna Eves, and COFAR member Richard Buckley also offered recommendations to the committee, including establishing a registry of caregivers found to have committed abuse of disabled persons, and potentially giving local police and district attorneys the sole authority to investigate and prosecute cases of abuse and neglect.

The hearing drew some mainstream media coverage (here and here); but, while COFAR had alerted media outlets around the state to the hearing, most of the state’s media outlets, including The Boston Globe, did not cover it.

Committee asks no questions

Following the hearing, Frain said he was glad to get the opportunity to testify, but frustrated that the members of the committee seemed to lack interest in what he and COFAR’s other panel members had to say.

“It crossed my mind, were the committee members told not to ask any questions?” Frain said. “How divorced and disengaged is the Legislature that they can hear this testimony and not even have a follow-up question about an agency they’ve voted to fund?”

The hearing was the second since January involving testimony invited by the Children and Families Committee on the Department of Developmental Services system. The general public was allowed to attend, but not permitted to testify publicly before the committee in either hearing. The committee has given no information regarding the scope of its review of DDS.

COFAR has continued to ask for information from the committee as to the full scope of its review, and whether the committee intends to produce a report at the end of that review.

COFAR panel describes abuse and neglect

On Tuesday, Richard Buckley testified about his 17-year quest for answers to his and his family’s questions about his brother’s death in a group home in West Peabody in 2001. Buckley’s developmentally disabled brother, David, had previously been sexually abused in a group home in Hamilton, and was ultimately fatally injured in the group home in West Peabody.

David Buckley received second and third degree burns to his buttocks, legs, and genital area while being showered by staff in the West Peabody residence run by the Department of Developmental Services. The temperature of the water in the residence was later measured at over 160 degrees.

David died from complications from the burns some 12 days later, yet no one was ever charged criminally in the case, and the DDS (then Department of Mental Retardation) report on the incident did not substantiate any allegations of abuse or neglect.

Richard Buckley urged the committee to take action to reform the DDS system. “If nothing is done, the next rape, assault or death, will be on you,” he said. “And we will remember that.”

Buckley also read testimony from another COFAR member, Barbara Bradley, whose 53-year-old, intellectually disabled daughter is currently living in a residence with a man who has been paid by a DDS-funded agency to be her personal care attendant. In her testimony, Bradley said the man initiated a sexual relationship with her daughter, and later brought another woman, with whom he also became sexually involved, to live in the same residence.

Anna Eves discussed the near-death of her son, Yianni Baglaneas, in April 2017, after he had aspirated on a piece of cake in a provider-operated group home. The group home staff failed to obtain proper medical care for Yianni for nearly a week after he aspirated. He was finally admitted to a hospital in critical condition and placed on a ventilator for 11 days.

DDS later concluded that seven employees of Yianni’s residential provider were at fault in the matter. Nevertheless, at least two of those employees have continued to work for the provider, Eves said.

“The systems that are in place are not working and we are failing to protect people with intellectual and developmental disabilities in Massachusetts,” Eves testified. “We have to do better.”

Eves urged the committee to support a minimum wage of $15 an hour for direct care workers, more funding for the Disabled Persons Protection Commission, and passage of “Nicky’s Law,” which would establish a registry of caregivers found to have committed abuse or neglect. Such persons would be banned from future employment in DDS-funded facilities.

Eves also noted that licensing reports on DDS residential and day program providers that she reviewed — including the provider operating her son’s group home — did not mention substantiated incidents of abuse or neglect. She said Massachusetts is falling behind a number of other states, which provide that information to families and guardians.

In his testimony, Frain also urged the committee to support more funding for the Disabled Persons Protection Commission, the state’s independent agency for investigating abuse and neglect of disabled adults. Because the agency is so grossly underfunded, he suggested that the committee consider either “fully funding” the agency or “partnering with the local police and district attorneys’ offices and let them investigate” the complaints.

Frain maintained that staffs of corporate providers, in particular, face pressure not to report complaints to the DPPC, and that the agency, in most cases, has to refer most of the complaints it receives to DDS. That is because the DPPC lacks the resources to investigate the complaints on its own.

Moreover, Frain maintained, the current investigative system is cumbersome. It can sometimes take weeks or months before either the DPPC or DDS begins investigating particular complaints, whereas police will show up in minutes and start such investigations immediately.

Frain also contended that “privatization of DDS services has been at the root of many of these problems.”

Other persons and organizations that testified Tuesday included DDS Commissioner Jane Ryder, the Arc of Massachusetts, the Massachusetts Disability Law Center, and the Massachusetts Developmental Disability Council.

COFAR is continuing to urge the Children and Families Committee to hold at least one additional hearing at which all members of the public to testify publicly before the panel. COFAR has also been trying to obtain a clear statement from the committee as to the scope of its ongoing review of the Department of Developmental Services.

For a number of years, COFAR has sought a comprehensive legislative investigation of the DDS-funded group home system, which is subject to continuing reports of abuse, neglect and inadequate financial oversight.

Gifts of the Sheltered Workshop

Guest post

Note: This post was written and sent to us from Thomas Spellman and Dona Palmer of Delavan, WI. Although all sheltered workshops were closed in Massachusetts as of 2016, we are still pushing for a resumption of work opportunities for clients of the Department of Developmental Services in this state.

As a result, we think Thomas Spellman’s and Dona Palmer’s points about sheltered workshops remain applicable to Massachusetts, just as they are applicable to work opportunities programs provided to developmentally disabled people across the country.

________________________________________________________________________________

Introduction

Before we present the gifts of the “Sheltered Workshop,” let us take a step back and look at the big picture. What we see among Sheltered Workshop participants is a continuum, from mild to severe brain impairment.

While these individuals are all disabled, their NEEDS differ significantly. A major contributing factor is behavior. While behavior is not a disability in and of itself, it can be a complicating factor in the employment of a disabled individual and in their life in general.

While the ability to “work” varies significantly among persons with brain impairment, behavioral issues and physical disability, those persons must do work that is meaningful to them. Whether it is just a smile or it is working for General Motors, the work must be meaningful to the person doing it.

As we all know, each person with a disability (or their guardian) has the right to choose where they “work” and where they live. This is a foundation of the Americans with Disability Act (ADA).

While the right of each person to choose is important, it is EQUALLY IMPORTANT that a variety of work experiences be available that address the varied needs of all of those individuals who are disabled. Sheltered Workshops MUST BE AVAILABLE to those with disability(ies), cognitive impairment, physical challenges and behavioral issues.

A sheltered workshop in New Jersey, which, unlike Massachusetts, has so far kept its sheltered workshops open

We know of the benefits of a Sheltered Workshop because our daughter Rosa has been working at VIP Service, a Sheltered Workshop in Elkhorn, Wisconsin, for fifteen years.

We use the term “Sheltered Workshop,” which in the past was accepted as a very good description of a safe place for people with disabilities to work. As we know, today it clearly is used by some in a derogatory manner, as in “You work at a Sheltered Workshop, and not in the community!! Poor you!”

Gifts of the Sheltered Workshop

First and foremost is the gift that the Sheltered Workshop exists!! (See note above about Massachusetts.) Without its existence, NONE of the rest of the Gifts WILL EVER BE REALIZED by the tens of thousands of disabled individuals who realize some or all of the Gifts every day!!!

Second is that there is WORK to do. While WORK is a human experience, and there is much written about WORK by others, we know from our own experience that WORK is fulfilling. Rosa has said that about the WORK that she has done at VIP.

While a person’s production rate may seem important, the more important issue is accuracy in order for WORK to be of economic value. Is the product that is being completed done exactly the way that it needs to be done? That is a challenge, and in some cases a major challenge to providing work to those who are disabled.

Third is the 1986 amendment to the Fair Labor Act of 1938, which provides for a “Special Minimum Wage” for persons with disabilities.

This is NOT a “Sub-minimum Wage. Sub-minimum Wage is a term that was coined by the National Disability Rights Network to negatively describe the “special minimum wage” as described by Section 14 (c)(A)(5) of the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938 as amended.

New terms such as prorated wages or commensurate wages are used, but it is the CONCEPT and not the name that is critical to the existence of Sheltered Workshops.

The logic underlying the “Special Minimum Wage” is simple and clear. If Rosa produced half what a full-time worker would produce, then she will receive half of the financial benefit for doing that specific job. It may need to be audited from time to time, BUT THERE IS NOTHING THE MATTER WITH the concept.

If we want significant meaningful WORK for people who have mild to moderate brain impairments and or physical impairments, then we MUST HAVE the Special Minimum Wage. If the Special Minimum Wage is ELIMINATED, Rosa and tens of thousands of others whose disabilities limit their ability to work WILL HAVE NO WORK AT ALL.

Fourth is The VARIETY of JOBS that an individual can experience. We have only recently realized the importance of this. Rosa has learned over 100 jobs in the fifteen years that she has worked at VIP. Each of those jobs required her to trust Pam, her supervisor; to listen to Pam, to comprehend what Pam is saying, and when necessary ask Pam for help on how to do something.

Having been with Pam for 15 years, Rosa is proficient at each of those tasks. The hardest thing for her was asking for help. The VARIETY of job experiences has allowed her to grow to become more independent.

It needs to be noted that while some individuals may be able to do a two or three-step assembly job, they may not be able to collate a ten-page letter. Some may be able to put labels correctly on a bottle while others cannot. This variety of JOBS is very, very important to the growth and health of all those who work at a Sheltered Workshop.

Fifth is that besides the variety of jobs, there is the allowance to work at different speeds. It makes no difference in a Sheltered Workshop if an assembly job takes a minute or ten minutes. To know that what you are doing, and the speed that you are doing it, is OK is very important. It is one of those things that one might not see as a Gift, but surely it is.

Sixth is the Stability of the Sheltered Workshop. The schedule stays the same. The workers are the same. There is a place to go to WORK and be with FRIENDS. There is a stability of workers and supervisors. For Rosa and, we assume, many others, KNOWING what tomorrow will bring is VERY, VERY important in their lives. She “implodes” emotionally when the “activities” (as she calls them) of the day are not known.

For Parents and Guardians, KNOWING that the Sheltered Workshop WILL BE THERE WHEN THEY are NO LONGER CAPABLE OF caring for their loved one, is of even GREATER IMPORTANCE! It is to know that the Social Contract to take care of a son or daughter who is disabled WILL BE HONORED by the community of the next generation.

Seventh is Family. For many individuals with disabilities, their personal living situation can be disrupted by a change of ownership of the residential facility that they call home. The “home” can be too expensive or it can be too big or not big enough, and of course it can close. When an individual is forced to change households, they lose that “family,” and so the stability of the people at a Sheltered Workshop becomes their family. As I was preparing this, I realized that Rosa will grieve our deaths with her Sheltered Workshop family.

Eighth is Safety. Both physical and personal safety are priorities at Sheltered Workshops. That extra caution is reassuring to both the workers and their parents and/or their guardians.

Ninth is Friends and Community. What is special about the Sheltered Workshop is that with time, true friendships do develop with both the other workers as well as with the supervisors.

Fifteen years ago, Rosa bonded with Pam, a PAID STAFF member at VIP Services. Rosa has shared with Pam the births of Pam’s girls, hearing the baby stories, and now watching the girls show their goats at the County Fair.

And now Pam has accepted the role of guardian if both of us become unable to be Rosa’s guardian. It is despicable to use the term PAID STAFF in a derogatory manner, which some disability rights individuals do. They imply that because someone is a paid staff member, there is not a real bond.

What is CRITICAL TO UNDERSTAND HERE is that our personal individual associations are part of what defines us as INDIVIDUAL HUMAN BEINGS. These relationships, in large part, will be with OTHERS much like ourselves. These relationships are our very essence. There must be an ACKNOWLEDGEMENT OF THIS MOST BASIC HUMAN FACT.

Tenth is that transportation is made available. A few Sheltered Workshop participants may be able to drive, but the vast majority of workers at Sheltered Workshops need a ride to work. In those cities with bus service and a Sheltered Workshop on the bus line, a few more individuals are able to catch the bus to get to work, but there still are a significant number, who without affordable transportation being provided, will NOT BE ABLE TO WORK.

Eleventh is the Staff. Yes, the staff of the Sheltered Workshop is a gift. Some disparagingly call them PAID STAFF, but they are a group of highly trained individuals giving of themselves in many ways that would not be easy for many of us to deal with on a daily basis. To imply that these tens of thousands of staff members can be replaced in the for-profit workforce now being called “community integrated employment” is beyond absurd.

Twelfth is that Sheltered Workshops allow participants to take extended vacation time, in turn allowing parents who are retired to take longer vacations without endangering their son’s or daughter’s job when they return. Will a Walmart allow a 6-week vacation? That’s the amount of time our family spends in Florida in March and April of each year.

Thirteenth is that Sheltered Workshops are also a backup for those persons who are having a hard time at their public employment place of work. It may be for a few weeks or it may be a permanent change, but it is critical that the Workshops be there. The alternative to not being successful at Public Employment Work CANNOT BE SITTING AT HOME WATCHING TV!!

Thomas Spellman and Dona Palmer can be contacted at tmspell@execpc.com

Advocacy group appears to say persons with even the most profound intellectual disability may not need guardians

We are questioning statements from a leading organization seeking to reduce or eliminate guardianships that imply that a guardian may not be necessary even for some of the lowest functioning people with intellectual or developmental disabilities.

In an email to me on September 27, Dari Pogach, a staff attorney with the American Bar Association’s Commission on Law and Aging, stated that decisions to appoint or terminate guardians “should not be based on diagnosis or condition.”

That statement appears to imply that an individual’s diagnosed level of disability is irrelevant in determining whether that person needs a guardian; and therefore, even the most profoundly cognitively impaired persons may not need guardians.

The ABA Commission is working with the National Center on Law and Elder Rights (NCLER) to replace guardianships with a more informal process called Supported Decision Making (SDM).

Under SDM, individual guardians are replaced by teams or “network supporters,” who enter into written agreements with disabled individuals to “help them make decisions” about their care, finances, living arrangements and other areas. The network supporters can include family members, but they can also include corporate service providers, according to the Center for Public Representation, which is pushing for SDM in Massachusetts.

COFAR is concerned that SDM, which is part of a growing effort to reduce or eliminate guardianships, could marginalize family members in decisions made about the care of their loved ones with developmental disabilities. That’s because it is primarily family members who seek to become guardians of incapacitated persons after they reach the legal age of adulthood at 18.

The VOR, a national advocacy organization for people with developmental disabilities, adds that SDM “could weaken protections for those who are the most vulnerable.”

Pogach’s full statement to me was as follows:

The decision to appoint a guardian in the first place, or terminate the guardianship, should not be based on diagnosis or condition, but rather on the person’s ability to make their own decisions, with or without support and to be safe from abuse, neglect and exploitation (my emphasis).

The problem with this statement, in our view, is that it raises a troubling question. If clinicians are not required or allowed to consider an individual’s clinical level of disability, how can they determine what a person’s ability is to make their own decisions? It would seem that in that case, that determination would become totally arbitrary.

Pogach’s statement draws no distinction between levels of intellectual or developmental disability, and appears to imply further that people even with the most severe or profound levels of such disabilities may be capable of making their own decisions about life choices and care without the need of a guardian.

Pogach was a panelist in an NCLER-sponsored webinar on August 22 that discussed efforts by the organization to terminate guardianships in a number of instances involving persons who were elderly or had developmental disabilities. As a member of the webinar audience, I submitted a written comment and a question to the webinar panelists. Pogach’s September 27 email was in response to my comment and question.

In my comment to the webinar panel, I stated that COFAR was concerned that SDM could “marginalize family members who we have found often make the best guardians for persons with intellectual and developmental disabilities.”

I also noted that severe and profound levels of intellectual and developmental disability present very different issues from moderate levels of those conditions, and we did not necessarily see those distinctions made by the webinar panelists.

Finally, I posed the question whether any protections were possible under SDM to ensure that a family member would not be “outvoted” on an SDM team by providers, clinicians and others who may not have the same degree of interest in the wellbeing of the disabled individual.

In her September 27 email in response, Pogach included the following statement:

The purpose of SDM is not to marginalize family members. SDM is predicated on the person being at the center of the decision-making process, and that includes choosing who will act as a (network) supporter. It is also means the person can choose to agree or not to agree with everyone in their supported decision-making network, including providers, clinicians, and family members. (my emphasis)

This response raises further questions and concerns for us. It appears to imply that not only can an individual with an intellectual or developmental disability, no matter how severe or profound, make their own decisions about their care, they can overrule family members and others on their SDM team or network.

While that viewpoint might appear to be simply meaningless if it were to be applied to extremely low-functioning persons, it is nevertheless concerning because it further implies that family members, in particular, should not be making decisions about the care of their developmentally disabled loved ones.

Pogach’s statement added that:

When supported decision-making is working, the person does not follow the majority vote of the (SDM network) supporters. The role of the supporters is to listen, help the person understand their options, and help the person to make their own decision. (my emphasis)

As noted, this viewpoint appears to make no distinction between people who are elderly, for instance, and persons with developmental disabilities, or between high functioning individuals with developmental disabilities and those with severe or profound levels of disability.

The fact that support for SDM has become an ideological position is evident in a statement in a law journal article by Leslie Salzman, a prominent SDM proponent:

Virtually everyone has the ability to participate in the decisions affecting his or her life, with the possible exceptions of persons who are comatose or in a persistent vegetative state. (my emphasis)

For Salzman, it’s apparently more likely than not that even a person in a persistently unconscious state can participate in making decisions about their care.

In an October 1 email in response to Pogach, I stated that we have seen instance after instance in which providers, clinicians, state agency managers, and other professionals have sided with each other and against family members in disputes over care of the individuals in question. The views and concerns of the family members are often dismissed or ignored in these cases, even though it is usually the family that knows the individual best. And, of course, family members are almost always the only people in this group with strong emotional bonds to the individual.

I also noted that the federal Developmental Disabilities Assistance and Bill of Rights Act (PL 106-402) states that “Individuals with developmental disabilities and their families are the primary decision makers regarding the services and supports such individuals and their families receive…” (my emphasis)

No distinction made between family members and professionals as guardians

While abuses in the guardianship system certainly occur, we think the potential for abuse is greater when professional guardians are involved than when family members are guardians. DDS pays attorneys and corporate entities to provide guardianship services to persons in cases in which family members are not available or have been removed as guardians.

As we have reported, there is relatively poor oversight of the professional guardianship system, at least in Massachusetts.

However, while SDM might be seen as a solution to the abuses committed by professional guardians, we are concerned that it may just shift the potential for exploitation from those professional guardians to corporate providers.

These state-funded providers have a direct financial stake in the care of persons with developmental disabilities. As such, including providers in an SDM network establishes a potential conflict of interest. Yet, the Center for Public Representation, a prominent SDM supporter, suggests that an SDM network can include “family members, co-workers, friends, and past or present providers.”

We have also reported that many of the same organizations that are advocating for SDM as an alternative to guardianships, including the Center for Public Representation, have also been involved in efforts to restrict congregate care and promote privatization of care for the developmentally disabled.

In sum, we do agree that significant reforms are needed in the guardianship/probate court system with respect to persons with intellectual and developmental disabilities. But we see that exploitation as being due primarily to rampant privatization and its connection to poor governmental oversight of professional guardians, and not to the appointment of family members as guardians.

SDM could be a viable component of the reform of the current system, provided there is an acknowledgement that SDM is not appropriate or suitable in every instance and that there are persons who simply cannot reliably make their own life choices and will ultimately need to have guardians. In cases in which SDM is determined to be an appropriate option, a way needs to be found to ensure that the family member or members on the SDM network remain the primary decision maker(s) on the network.

I noted to Pogach that the following are some of the additional reforms we have proposed to the system:

- Increased financial oversight of the corporate provider system and the DDS/probate guardianship system.

- Passage of legislation requiring probate court judges to presume that family members are suitable guardians of persons with intellectual and developmental disabilities.

- The provision of free legal assistance to family members and guardians who been barred from contact with their loved ones in the DDS system or who have otherwise faced retaliation from the Department or from providers.

- The provision of free legal assistance to family members whose guardianships are challenged by DDS.

- A policy statement by DDS that the Department will make every effort to comply with the Developmental Disabilities Assistance and Bill of Rights Act, and, in particular, the statement in the law that individuals with developmental disabilities and their families are the primary decision makers.

We’re anxious to hear back from Pogach on this. Unfortunately, the movement to reduce or eliminate guardianshps appears to be yet another area in which ideology is replacing both common sense and scientific, evidence-based policy making. We need to maintain those latter values.

Senator Warren’s concern about payment of subminimum wages to developmentally disabled people is misplaced

Massachusetts Senator Elizabeth Warren has proven to be one of the nation’s most effective advocates for workers and their financial security; but we think she’s wrong in charging that persons with intellectual and other developmental disabilities are being exploited by work programs that pay them a subminimum wage.

Warren is leading an effort in Congress to eliminate waivers that have allowed employers to pay a subminimum wage to disabled persons who are hired by employers in mainstream work settings. Warren alleges that payment of subminimum wages under the so-called 14(c) certificates or waivers is exploitative and discriminatory.

We would agree that for disabled people with normal intellectual functioning, payment of subminimum wages is exploitative and unnecessarily discriminatory; but a distinction needs to be made in the case of persons who have intellectual or other developmental disabilities that severely limit cognitive functioning.

In not making this distinction in calling for the elimination of the subminimum wage waivers, Warren is making the same well-intentioned mistake that many people in the advocacy community have made. That mistake is to assume that all developmentally disabled people are exactly the same as non-disabled people in terms of their employment potential and, even more importantly, their employment aspirations.

Those assumptions overlook a number of realities, including the fact that virtually all developmentally disabled persons who are placed in those work programs receive government assistance in some form for residential care, day care, or other services. Unlike non-disabled persons, most, if not all, individuals with significantly impaired cognition are not seeking to support themselves financially through work. They are seeking to occupy their time with activities that are meaningful and satisfying to them.

As the brother of an intellectually disabled person noted to me, his brother has no understanding of the concept of money, and wouldn’t know or be able to appreciate whether he was paid a minimum wage rate or not.

In an April 23 letter to U.S. Labor Secretary Alexander Acosta, Warren and six other senators attempted to link payment of subminimum wages to problems of abuse and poor work conditions in work settings for people with developmental disabilities. The letter cited four instances in which disabled persons were forced to work in sweatshop-like conditions, including a case in Iowa in which intellectually disabled men were working in a turkey processing plant for little or no wages and were subjected to verbal and physical abuse and unsanitary conditions.

But as is the case with abuse or poor conditions in any care-related or work setting, the instances cited in Warren’s letter appear to be the result of poor governmental oversight of those programs. Those problems could have been avoided or could be rectified with proper oversight. The problems were not necessarily the result of payment of subminimum wages.

Moreover, citing isolated instances of abuse in specific work settings doesn’t prove it is a problem in all work settings. In fact, we have not heard of any instances of such exploitation or abuse occurring in sheltered workshops or other work activity programs in Massachusetts.

We have made a number of attempts to contact Warren about this issue. I left separate voicemail messages since Monday of this week with Warren’s Washington and Boston Senate offices. On Monday, I also posted what was essentially this blog post on her website contact page, and asked if she or her staff would respond. To date, I’ve gotten no response and no call back.

The unfortunate impact of the effort to prohibit employers from paying subminimum wages to developmentally disabled people is that rather than paying them higher wages, most employers choose not to employ them. So the end result is that these disabled individuals miss out on satisfying and meaningful ways to occupy their time.

As we have reported, DDS data show that the number of developmentally disabled persons being placed in integrated or mainstream employment paying at least the minimum wage in Massachusetts has been steadily dropping in the past few years.

During Fiscal Year 2016, a high of 509 clients in the Department of Developmental Services system newly started working in mainstream jobs. That number dropped to 127 clients entering integrated employment during Fiscal 2017, and to a net increase of only 98 clients during Fiscal 2018.

We are assuming that demand for these mainstream jobs remains high, possibly in the thousands. That there was a net increase of less than 100 developmentally disabled persons in integrated employment in Fiscal 2018 appears to show that the administration has been unable to find jobs for people who want them.

Promises in closing sheltered workshops haven’t been kept

In 2014, the administration of then Governor Deval Patrick began closing sheltered workshops in Massachusetts that provided developmentally disabled persons with piecework activities because those facilities supposedly segregated those persons from their non-disabled peers and paid them less than minimum wage. The Baker administration followed that same policy, ultimately closing all remaining workshops as of the fall of 2016.

The plan of both administrations was to provide training to those former workshop participants and place them in mainstream workforce settings along with supports that would help them to function in those settings.

We expressed concerns at the time, however, that the workshop closure policy was being pursued without knowing, among other things, whether sufficient jobs existed in the private sector for all of those former workshop participants and others who want jobs.

Unfortunately, our concerns have proved to be well founded. Instead of being placed in mainstream or integrated jobs, the vast majority of the former sheltered workshop participants have ended up in DDS-funded Community Based Day Supports (CBDS) programs, which offer little or no work opportunities, and have left many of those people frustrated and bored.

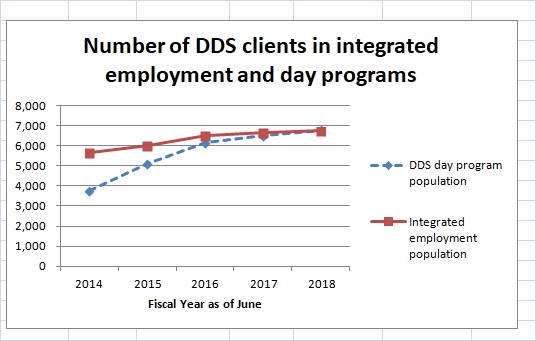

DDS data also show that the DDS day program population increased by 81% from Fiscal 2014 through 2018 in Massachusetts while integrated job placements increased by only 19%. The chart below reflects this trend and illustrates the fact that the total day program population in the DDS system has caught up with and even surpassed the total number of departmental clients in integrated employment since Fiscal 2014.

Barbara Govoni, the mother of one former sheltered workshop participant, is continuing to advocate for legislation that would allow for the return of piecework activities in her son’s CBDS program.

Direct care workers are the ones who are exploited

Ultimately, Senator Warren’s concern about exploitation is misplaced. It is not the developmentally disabled who are exploited by subminimum wages. Rather, it is the people who are hired by DDS-funded providers to care for them who are usually the victims of systematic exploitation in this field.

As we have noted, direct-care workers in the DDS system, who do have to work in order to feed themselves and their families, are the ones who Senator Warren and other advocates for the disabled should be concerned about.

When direct-care workers are underpaid, it is not only they and their families who suffer, but the very people who depend on their services who suffer as well from substandard care. Paying developmentally disabled people less than minimum wage as part of their work programs doesn’t harm them. Paying their caregivers less than a living wage does.

Connecticut has moved ahead of Massachusetts on direct-care worker wages

It apparently took the threat of a major strike, but the Connecticut Legislature passed a bill and the Connecticut governor signed it earlier this year to raise the minimum wage of direct-care workers in that state’s Department of Developmental Services system to $14.75 an hour, starting January 1.

A similar effort fell short last year in Massachusetts when a budget amendment to raise direct-care wages to $15 was killed in a budget conference committee in the Massachusetts Legislature.

While Governor Charlie Baker signed separate legislation in June to raise the minimum wage across the board in Massachusetts to $15, that wage level won’t actually be reached until 2023. The minimum wage will rise to only $12 next year, whereas it will be close to $15 in Connecticut for human services workers as of January 1.

It seems that even though legislators and the administration of Governor Dannel Malloy in Connecticut are equally as tolerant of runaway privatization as they are here in Massachusetts, the Connecticut Legislature and governor have shown a greater recognition that increased privatization has resulted in low wages for direct care human service workers, and that low wages have had a negative impact on services.

In May, after the Connecticut Senate voted overwhelmingly in favor of setting the minimum direct-care wage at $14.75, Malloy made a statement that we have yet to hear Governor Baker make:

“For far too long,” Malloy said, “the people who provide care to our most vulnerable neighbors have been underpaid for their critical work.”

In fairness to Baker, Malloy made that statement only after 2,400 employees of nine corporate provider agencies in Connecticut voted in April to authorize a strike that was set to begin in early May. The workers in Connecticut are represented by the SEIU 1199 New England union.

Clearly hoping to avert that strike, the Malloy administration proposed raising the minimum wage for human services workers to $14.75 an hour and providing a five-percent raise for workers earning more than $14.75 an hour effective January 1.

The Malloy administration’s proposal, which was endorsed by the SEIU union and ultimately signed into law, applies to 19,000 union and non-union caregivers that staff some 170 group homes and other nonprofit agencies that receive Medicaid funding in Connecticut, according to The Connecticut Mirror.

As Connecticut Senate President Pro Tempore Martin Looney noted:

The work (those caregivers) do is among the most important in our state in terms of humanity. If we are to consider ourselves a humane and caring society, at long last we should begin at least to recognize the value of that work.

In Massachusetts, SEIU Local 509 helped organize a five-day strike for a living wage in July at CLASS, Inc., a DDS-funded day program provider based in Lawrence. The workers there were getting paid about $13 an hour and wanted a $1 increase. The company was offering an increase of only 40 cents.

The president of CLASS, meanwhile, was making about $187,500 a year, according to the state’s online UFR database.

In July, workers at CLASS, Inc. reached a settlement with management to raise the workers’ wages by 60 cents an hour. That would still leave the average worker there well below what direct-care workers will be earning in Connecticut.

The Massachusetts strike, moreover, didn’t have the impact on legislators and other policy makers here that the threat of the Connecticut strike apparently did in that state. Thus far, it isn’t apparent that there is any political will in Massachusetts to raise the minimum wage of direct-care workers to Connecticut’s level.

That is concerning because five years is a long time to wait for the minimum wage for direct-care workers to reach $15. Due to inflation alone, that $15 will be worth less to Massachusetts workers in 2023 than it would be if they were to receive it starting this January.

Our September newsletter questions the Children and Families Committee’s role in investigating DDS

Each issue of our newsletter, The COFAR Voice, tends to have a theme that units most of the articles.

The theme running through the September issue, which we posted last week on our website, has to do with questions about the role of the state Legislature’s Children, Families, and Persons with Disabilities Committee in investigating care and conditions in the Department of Developmental Services system.

That role that the committee is playing is, to say the least, unclear. As the newsletter notes, the committee appeared to open its review of DDS last January when it scheduled an informational hearing on abuse and neglect in the DDS system. But while numerous family members and guardians of DDS clients showed up, ready to share their accounts of their experiences with the system, they weren’t permitted to testify during the public hearing.

State Senator Joan Lovely, Senate chair of the Children and Families Committee (left), and Barbara Govoni.

The committee invited only DDS Commissioner Jane Ryder and Nancy Alterio, executive director of the Disabled Persons Protection Commission, to testify publicly. Members of the public were allowed only to submit written testimony.

As we have noted to the committee, written testimony alone is limited in its accessibility to others and therefore in its impact and ability to inform the public at large.

As of late August, the committee was planning to hold a second hearing, but even then — seven months after the initial hearing — no decision had been made as to whether members of the public would be allowed to testify in public before the panel.

It’s unclear why the committee is so reluctant to allow public testimony on these critically important issues. In fact, we see no basis at all for that reluctance.

Also unclear, even at this juncture, is the scope of the committee’s overall review. We have not gotten an answer from the committee co-chairs when we have asked for specifics on that scope.

We have long sought a legislative investigation of the DDS-funded group home system, which is subject to continuing reports of abuse and neglect and inadequate financial oversight. Is the Children and Families Committee really interested in undertaking a comprehensive investigation? No clear answer to that question has been forthcoming.

We also raise questions in the September newsletter about the committee’s decision in June to effectively kill a bill that would have provided work opportunities for clients of DDS-funded day programs. To be fair, that decision was made amid continuing confusion over federal and state rules governing those work activities.

In mid-August, Barbara Govoni, a COFAR member who proposed the work opportunity bill, and I met with Senator Joan Lovely, Senate chair of the Children and Families Committee, to discuss the legislation, the DDS review, and related issues. We are hoping to continue to work with the committee to clear up the confusion over the work opportunity issue and to help get new legislation enacted and passed in the coming legislation session, which starts in January.

We have also offered on a number of occasions to provide information to the committee about care and conditions in the group home system.

Other important stories in our September newsletter concern:

- The decision by the state’s Public Records supervisor to uphold the secrecy of virtually all reports done by the Disabled Persons Protection Commission, and

- How direct-care workers at two DDS-funded day program agencies won at least partial victories in their fight for adequate wages and working conditions,

and more.

You can find the new newsletter on the home page of our website and on our newsletters page. Please check it out.

Has the Globe just shown a newfound, if inadvertent, support for the Pacheco Law?

Although we are an advocacy organization that focuses on human services, we have at times waded into the ongoing controversy over the operation of the MBTA in Boston.

The reason for that has to do with a now decades-long debate over privatization of public services and the implications of the Pacheco Law in that regard.

On Sunday, The Boston Globe reiterated its support for the privatization of T functions with an editorial that defended the current contracted operation of the T’s problem-plagued commuter rail system.

As a supporter of privatization, the Globe has, in recent years, been at the forefront of the long-running criticism in political and journalistic arenas of the Pacheco Law. But in calling on Sunday for a cost-benefit analysis prior to any proposed move to bring the T’s commuter-rail system in house, it seems to us that the Globe is also endorsing, if inadvertently, the principles and intent of the law.

The Pacheco Law requires state agencies seeking to privatize existing operations to do a cost-benefit analysis that demonstrates that the cost of privatizing the service would be lower than continuing to do the service in-house, and that the quality of service would be equal or better if it were privatized.

The Pacheco Law, which was enacted in 1993, has been a lightning rod for political criticism and controversy over the years. Much of the state’s political establishment and prominent journalistic institutions have been harshly critical of it.

We have supported the law because we see it as providing a potentially important layer of oversight and analysis in the ongoing privatization of services for the developmentally disabled in Massachusetts.

In a 2011 editorial, the Globe called the Pacheco Law “an affront to common sense,” and charged that it was allowing public employee unions to place their “demands” above “the obligation to run government efficiently.”

But in its editorial on Sunday, the Globe actually put forth an argument that appears, without directly admitting to it, to endorse the precepts of the Pacheco Law. In criticizing calls by Democratic candidates for governor for in-house operation of commuter rail when the current contract with Keolis expires in 2022, the editorial states:

Whoever is in charge in 2022, though, here’s a suggestion: Since in-house management is an idea that refuses to die, [and I would add, so is privatization, for that matter!] the state should ask the T to submit a plan showing what it would entail. If nothing else, that would clarify for the public the costs and benefits, and bring some specifics to what is now little more than a vague applause line for Democrats. (my emphasis and insertion in brackets)

That is exactly what the Pacheco Law calls for when state agencies seek to privatize services. What the Globe is calling for is the same type of cost-benefit analysis, only in reverse — from privatized services to in-house. To me, it actually sounds like a good idea.

The Sunday editorial further states that while the state “can definitely do a better job with commuter rail after its current contract with Keolis expires in 2022…the goal of better service, not adherence to ideological precepts, should guide the next governor.” (my emphasis)

Agreed, and that is also the goal of the Pacheco Law, which is to ensure better service and lower cost rather than privatizing based on ideological precepts.

The editorial contends that:

…the T doesn’t have — and never has had — the in-house ability to operate the commuter lines itself, and dumping the commuter rail system directly into an already overburdened agency risks disruption. It could also raise thorny union issues, probably raising labor costs. And there’s no reason to expect running the commuter rail in-house would result in better service. (my emphasis)

Maybe not, but in-house operation of commuter rail might actually result in cost savings.

We reported in 2015 that the annual cost to the MBTA of contracting for commuter rail services had risen by 99.4 percent since 2000, compared with a 74.9 percent increase in the annual cost of the agency’s in-house bus operations, according to cost information we compiled from public online sources.

Finally, the Globe editorial suggests that rather than bringing management of commuter rail in house, the T should consider offering the next contractor “a longer-term deal, to better align the incentives of the contractor and the state and potentially bring in private-sector money for capital investments.”

I would note here that long-term contracts are not necessarily better deals for the state or consumers. It is difficult if not impossible to project financial risks over long periods of time. As a result, long-term contracts tend to have provisions that protect private contractors from those risks while transferring the risks to the public.

Also, private investments for capital improvements must be repaid by taxpayers and riders, and those deals can be very expensive to the public. Often there is little transparency in the terms and provisions of private investment arrangements in public infrastructure.

All of these are reasons why the Pacheco Law is necessary and important to the continued efficient and effective operation of government. The law provides for an open and detailed analysis and discussion of costs and benefits when public and private services and functions come together.

Confusion reigns over employment of the developmentally disabled in Massachusetts

When it comes to the crucial issue of employment of people with developmental disabilities in Massachusetts, the policies of both the federal government and the Baker administration appear to be unclear, confusing, and to contain a number of contradictions.

Yet, neither the Baker administration nor the Massachusetts Legislature, in particular, seem to be showing much interest in clearing things up.

Consider these facts:

- Although the Patrick and Baker administrations stated that they were closing all sheltered workshops in Massachusetts in order to place developmentally disabled people in so-called “integrated” or mainstream work, those mainstream jobs have proven to be difficult for many, if not most, of those people to find.

- An unknown number of former sheltered workshop participants, some of whom do not want mainstream work, have been left without work of any kind in their Department of Developmental Services-funded day programs.

- It is unclear what work arrangements are considered by both the federal and state governments to be legal. In one case, DDS has resorted to a creative, if jerry-rigged arrangement under which a developmentally disabled man has been placed on the staff of his day program so that he can continue to do piecework there in compliance with federal rules.

Barbara Govoni (right) with state Senator Joan Lovely, Senate chair of the Children, Families and Persons with Disabilities Committee, this week. The Committee did not approve a bill Govoni proposed that would ensure work opportunities for her son and other developmentally disabled persons. But Lovely says she wants to work with Govoni on the issue.

Let’s look at each of these issues a little more closely:

Integrated work is apparently still unavailable for many who want it in the mainstream workforce

In 2014, the administration of then Governor Deval Patrick began closing sheltered workshops that provided developmentally disabled persons with piecework activities because those facilities supposedly segregated those persons from their non-disabled peers and paid them less than minimum wage. The Baker administration followed that same policy, ultimately closing all remaining workshops as of the fall of 2016.

The plan of both administrations was to provide training to those former workshop participants and place them in mainstream workforce settings along with supports that would help them to function in those settings.

We expressed concerns at the time, however, that the workshop closure policy was being pursued without knowing, among other things, whether sufficient jobs existed in the private sector for all of those former workshop participants and others who want jobs. We also expressed concern that the Legislature wasn’t following through with funding needed for training.

Since 2014, data appear to have borne out our concerns.

DDS data provided to us last month show that despite the workshop closures, smaller and smaller numbers of people have actually entered the integrated or mainstream workforce in Massachusetts since Fiscal 2016. During that fiscal year, a high of 509 clients in the DDS system newly started working in mainstream jobs. That number dropped to 127 clients entering integrated employment during Fiscal 2017 and a net increase of 98 clients during Fiscal 2018.

We are assuming that demand for these mainstream jobs remains high, possibly in the thousands. That there was a net increase of less than 100 developmentally disabled persons in integrated employment in Fiscal 2018 appears to show that the administration has been unable to find jobs for people who want them.

Fiscal years 2015 and 2016 were apparently the years in which most of the population of the sheltered workshops left those programs and in which most of the increases in integrated employment programs took place. The problem is that the numbers of clients entering integrated employment in those years were much smaller than the numbers entering DDS-funded day programs.

Overall, the DDS day program population increased by 81% from Fiscal 2014 through 2018 while integrated job placements increased by only 19%. The chart below reflects this trend and illustrates the fact that the total day program population in the DDS system has caught up with and even surpassed the total number of departmental clients in integrated employment since Fiscal 2014.

Source: DDS

When we asked DDS for any records indicating whether the Department is having a problem providing suitable work opportunities for those who want them, DDS referred us to two policy documents dated 2010 and 2013. But those documents obviously do not provide any information about the situation today.

One of those policy documents is the Department’s 2010 “Employment First” policy statement, which called for “integrated employment as a goal for all” DDS clients. The policy statement also called for a “consistent message” and an “infrastructure including prioritizing and directing of resources, that supports this effort.” (my emphasis)

To date, however, neither a consistent message nor an adequate infrastructure appear to exist to support that goal of universal integrated employment.

The DDS’s 2013 document, titled “Blueprint for Success,” stated that it was the Department’s goal to close all remaining sheltered workshops as of June 30, 2015. (The last workshops were closed a little more than a year later.)

The title page of the Blueprint states that the document was prepared by DDS and by the Massachusetts Association for Developmental Disabilities Providers (ADDP) and the Arc of Massachusetts. Both the ADDP and the Arc are largely supported by DDS-funded providers, which have benefited from higher DDS funding for the day programs to which most of the former sheltered workshop participants have been transferred.

Some DDS Employment First website links don’t work

In response to our request for documents and information, DDS also referred us last month to its Employment First website. It isn’t apparent, however, that the website contains any information that indicates whether or not it is difficult for developmentally disabled persons to find mainstream employment.

In one case in which I clicked on the website and then went to the “Career Planning” section under the “Resource Library,” a link to a “Career Planning Guide” took me to an error page. Another link to a “Guide to Person-Centered Planning for Job Seekers” took me to a page with generic advice on seeking employment, but no information on current job prospects for people with developmental disabilities in Massachusetts.

Under a link called “Program Development and Management,” I clicked on another link labeled “Ensuring Excellence in Community Based Day Supports,” and got another error page message.

Barbara Govoni and Patty Garrity, two of the more active family members of former sheltered workshop residents, both said they had never been referred to the website by DDS.

Legislative committee kills work opportunities bill

Last year, state Representative Brian Ashe of Longmeadow filed a work opportunity bill (H. 4541) at the request of Govoni, the mother of Danny Morin, a former sheltered workshop participant. The bill would have required optional work activities in DDS-funded day programs for up to four hours a day.

Govoni is concerned that Danny has been provided with few activities that are meaningful to him after his workshop closed in 2016, and misses the steady work that the workshop provided. She terms this lack of available work opportunities for Danny and others a human rights issue.

But Govoni’s bill was referred to the Children, Families, and Persons with Disabilities Committee, which effectively killed the measure in June by sending it to a study. Earlier this week, Govoni and I met with state Senator Joan Lovely, the committee’s Senate chair, to discuss the bill among other DDS issues.

Lovely said the employment bill was filed late in the two-year legislative session. She noted there was little time to analyze the implications of the bill, so the committee decided to send it to a study. The problem with that is that no one in the Legislature actually does such studies. Sending a bill to a study is a euphemistic expression used for killing a bill.

But Lovely said the committee is concerned about the work opportunity issue, and said the committee has been in touch with DDS about it. One proposal being discussed is to hire an ombudsman in the Department who would help individuals and families locate existing day programs that offer work opportunities.

Another proposal under consideration is to establish new work opportunities programs in existing day programs without making such work opportunities a legislative requirement of DDS.

But it isn’t clear that DDS really is working to establish those programs or whether the Department even considers work activities in day programs to be legal.

A staff member for Representative Ashe said she was told by DDS officials that the Department is essentially hamstrung by federal rules that prevent DDS day programs from offering any work activities because such activities can only be offered in “integrated” settings.

DDS tries creative approach to comply with federal requirements

Despite that, we have heard of recent cases in which arrangements have been made to provide work activities in DDS day programs. Patty Garrity’s bother, Mark, is one of those cases.

As we reported last year, Mark, like Danny Morin, was bored in his day program after it had ceased operating as a sheltered workshop. He wasn’t interested in the classes on painting, cooking, or money management that had replaced the piecework he had enjoyed doing.

In March of 2017, Mark’s day program found paper shredding work for him that DDS determined was in compliance with federal rules.

Ashe’s aide queried DDS about Mark’s case and was told that in order to allow Mark to do the paper shredding work under the new federal rules, the provider agency running his day program has actually placed him on its staff and is paying him minimum wage. As a result, Mark is now considered to be working in an integrated setting.

Ashe’s aide told us that Mark’s work arrangement is considered a “unique circumstance.”

Federal rules regarding integrated employment are unclear

The problem with unique arrangements such as Mark’s, however, is that they don’t necessarily solve problems involving larger groups of people. And it may even be questionable whether Mark’s arrangement was actually necessary.

Despite what DDS told Ashe’s legislative aide, it does not appear clear that the federal rules strictly forbid work activities in day programs such as Mark’s.

In an informational bulletin issued in 2011, the federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) stated that federal Medicaid funding will not cover “vocational services delivered in facility based or sheltered work settings, where individuals are supervised for the primary purpose of producing goods or performing services.”

That would appear to preclude at least some work activities in DDS day programs. But it seems possible that what the CMS bulletin refers to as “pre-vocational services” do allow for at least certain work opportunities in those settings, although the guidance, as usual, is vague. It also isn’t clear which types of work activities DDS recognizes as pre-vocational services and which it considers vocational.

The CMS bulletin offers a rather vague and clunky definition of pre-vocational services as:

…services that provide learning and work experiences, including volunteer work, where the individual can develop general, non-job-task-specific strengths and skills that contribute to employability in paid employment in integrated community settings. (My emphasis).

The bulletin does state that persons doing pre-vocational activities can be paid for those activities “in accordance with applicable Federal laws and regulations.”

The bulletin implies that these pre-vocational work opportunities can be provided in “fixed-site facilities,” which we think would include DDS day programs, although this again is not clear. Also, the bulletin states that these work opportunities must occur “over a defined period of time,” which implies that the individuals are ultimately expected, as the bulletin says, to be placed in permanent integrated employment. Once again, the “defined period of time” isn’t defined!

It’s also unclear to us what the CMS bulletin means in stating (above) that while pre-vocational services can include “work experiences,” they must provide the person with “non-job-task-specific strengths and skills.” Does that mean that the individual can do work but can’t do specific tasks?

It seems that the paper shredding activity that Mark Garrity is doing could be considered a “work experience.”

As a result, it seems possible that when Govoni’s bill is refiled, as we hope it will be in the next legislative session in January, the bill should specify that all DDS day programs be required to offer pre-vocational activities to anyone who requests that.

When Govoni and I met with Senator Lovely, Lovely agreed that the current rules governing work opportunities are confusing and need to be clarified.

The federal and state models are ‘one size fits all’

The CMS bulletin recognizes that work is vitally important to people with developmental disabilities in the same way it is important to non-disabled persons. As the bulletin notes:

Work is a fundamental part of adult life for people with and without disabilities. It provides a sense of purpose, shaping who we are and how we fit into our community.

Yet, after that acknowledgement, the CMS bulletin appears willing to ensure that fundamental part of life only for those who agree to work in the mainstream workforce. The bulletin states:

…Because (work) is so essential to people’s economic self sufficiency, as well as self esteem and well being, people with disabilities and older adults with chronic conditions who want to work should be provided the opportunity and support to work competitively within the general workforce in their pursuit of health, wealth and happiness.

Neither the federal government nor the Baker administration in Massachusetts appear to recognize that at least some persons with the most profound levels of disability are not able to participate in the mainstream workforce.

The CMS bulletin states the following:

All individuals, regardless of disability and age, can work – and work optimally with opportunity, training, and support that build on each person’s strengths and interests. Individually tailored and preference based job development, training, and support should recognize each person’s employability and potential contributions to the labor market.`(my emphasis)

The DDS Employment First policy referred to above appears to go even further in that regard, stating that:

It has now been clearly demonstrated that individuals who were previously considered unemployable in integrated community settings can work successfully. Even for those individuals with the most significant level of disability, through careful job matching and support design, employment has been shown to be a viable option. (my emphasis)

These statements are unsupported by the evidence. That is probably why neither statement provides any evidence to support its claims.

Recently, however, the federal government proposed changes at least to rules that prevent developmentally disabled persons from working for less than the minimum wage.

We hope to work with the Baker administration and the Legislature to find ways to penetrate and clear up this dense thicket of confusion and contradictions that has grown up in the past several years over the vital issue of work for the developmentally disabled.

We hope Govoni’s work opportunity bill is enacted in the next legislative session. In the meantime, legislators, advocates, and policymakers need to get together to clarify and agree on what can and should be done.

Direct-care human services workers fight inch by inch for better wages and conditions

Two ongoing cases involving human services workers are illustrative of the challenges those workers face in getting decent wages and working conditions, particularly in privatized facilities funded by the state.

In both cases, the SEIU Local 509 human services union has either represented the workers or has tried to organize them to join the union.

In an interview, Peter MacKinnon, the president of the local, discussed the cases and the implications they have for care throughout the Department of Developmental Services system.

Earlier this month, workers at CLASS, Inc., a DDS-funded day program provider based in Lawrence, engaged in a five-day strike at the facility for a living wage.

MacKinnon said that although the CLASS strike ended on July 13, the contract dispute had not been resolved. The workers there are getting paid about $13 an hour and wanted a $1 increase. The company is only offering an increase of only 40 cents.

The president of CLASS made about $187,500 a year in Fiscal Year 2017, according to the state’s online UFR database. The CFO made $132,900 that year.

Last month Gov. Baker signed a bill into law that would establish a $15 an hour living wage as of 2023.

In a second ongoing case, the National Labor Relations Board filed a complaint against Triangle, Inc., another DDS day program provider, over allegations that the provider had fired some of its workers for trying to organize a vote to join the SEIU.

MacKinnon said that Malden-based Triangle recently agreed to a settlement of that case under which the fired workers will be either reinstated or provided with financial compensation, and a vote to unionize will be held early next month. He said the union is satisfied with the settlement.

We published a blog post in March noting that Triangle had received $10.2 million in revenue in Fiscal 2017, including $6.9 million in funding from DDS, according to the state’s online UFR database. Coleman Nee, the Triangle CEO, was listed on the UFR database as having received $223,570 in total compensation in Fiscal 2017. That may not have covered an entire year with the agency.

That year’s tax filing listed six executives as making over $100,000 at Triangle.

MacKinnon noted that human services workers:

…do some of the hardest work in the human service field, and these are folks who are getting paid the least…When you have pay that low and work that difficult, it causes difficulties in retaining and recruiting staff.

Both COFAR and the SEIU have reported on the huge disparity in pay received by provider executives and direct-care workers in the DDS system. We reported in 2012 that workers for DDS-funded providers had seen their wages stagnate and even decline in recent years while the executives running the corporate agencies employing those workers were getting double-digit increases in their compensation.

In January 2015, a larger COFAR survey of some 300 state-funded providers’ nonprofit federal tax forms found that more than 600 executives employed by those companies received some $100 million per year in salaries and other compensation. By COFAR’s calculations, state taxpayers were on the hook each year for up to $85 million of that total compensation.

Nevertheless, much of the mainstream media still does not appear to understand this dynamic. The Lawrence Eagle Tribune quoted a spokesperson for CLASS, Inc. three days after the CLASS, Inc. strike began as saying the state had reduced rates to the providers to pay workers.

In fact, as the SEIU has reported, a 2008 law known as Chapter 257 enabled human services providers in the state to garner some $51 million in net or surplus revenues (over expenses) in Fiscal 2016. Yet, while raising wages of direct-care workers was a key goal of Chapter 257, those workers were still struggling to earn a living wage” of $15 per hour as of 2016, according to the SEIU.

The SEIU report, which got minimal news coverage, noted that Chapter 257 helped boost total compensation for CEOs of the corporate providers by 26 percent, to an annual average of $239,500.

The struggle to make headway in bringing about better pay and conditions for human services workers is a painstaking one. “If you want to attract and retain qualified experts in direct care, you need education, training, and in some cases advanced degrees, so you have to compensate these people fairly,” MacKinnon noted. “The old adage that a bad boss is the best organizer really holds true.”

MacKinnon said Local 509 now represents about 6,700 human services workers in Massachusetts working for about 40 providers of DDS and the departments of Mental Health, Children and Families, and Elder Affairs. That’s a good number, but still only a small fraction of the providers out there.

Next month, we’re scheduled to meet with state Senator Joan Lovely, the Senate chair of the Legislature’s Children, Families, and Persons with Disabilities Committee. Among the messages we hope to convey in the meeting are that the Legislature needs to get involved in helping fight for better pay and conditions for those caring for some of the most vulnerable members of our society.

Questions remain as key disabilities committee kills work opportunities bill

The Legislature’s family and disabilities rights committee has rejected H. 4541, a bill intended to ensure that developmentally disabled individuals get work opportunities in their state-funded day programs.

A staff member of the Children, Families, and Persons with Disabilities Committee said the committee understands many people cannot find those work opportunities and is therefore discussing other possible ways of providing for them. But details regarding the policies being considered by the Children and Families Committee are sketchy, and the committee hasn’t yet responded to written questions about those ideas.

Barbara Govoni, the mother of a developmentally disabled man, had pushed for months for passage of H. 4541, which would have established optional work activities in DDS-funded day programs for up to four hours a day.

Many people in community-based day programs funded by the Department of Developmental Services have not been able to find such work since all sheltered workshops were closed in Massachusetts in 2016.

H. 4541 had been referred to the Children and Families Committee in May, and the committee effectively killed the measure last month by sending it to a study. With formal business in the current two-year legislative session ending on July 31, any similar legislation will have to be re-filed next January and go through the legislative process all over again.

It isn’t clear what the committee’s objections were to H. 4541. We’ve noted that some committee members appeared to have some misconceptions about the bill, including the idea that it would bring sheltered workshops back to the state.

In fact, the bill would have simply provided work activities for individuals who continued to desire those activities in their day programs, and who either could not or did not want to work in “integrated” or mainstream work settings. As we have reported, many of these people miss the work they used to do in their sheltered workshops, and are unable to relate to most day program activities that replaced that work.

At the same time, it appears that some DDS-funded day programs are, in fact, continuing to offer work activities to some residents. It’s not clear how many such programs currently exist.

A legislative aide to Representative Kay Khan, House chair of the Children and Families Committee, said earlier this week that the committee had been in touch with the Department of Developmental Services about the work opportunity issue, and that one proposal discussed was to hire an ombudsman in the Department who would help individuals and families locate existing day programs that offer work opportunities.

Funding remains a question

Another proposal under consideration by the Children and Families Committee and DDS is to establish new work opportunities programs at additional day programs without making such work opportunities a legislative requirement of DDS.

No details are yet available, however, on the scope of the Children and Families Committee’s or DDS’s proposals. Also unknown is how funding would be appropriated for an expansion of existing work opportunities programs, and what the amount of that funding might be.

The Legislature, unfortunately, has previously shown a reluctance to fund job training and other programs as part of the effort to replace sheltered workshop programs with “integrated” or mainstream work opportunities for DDS clients.

The administration of then Governor Deval Patrick and the Legislature had set up a DDS line item in Fiscal 2015 to fund job training and other programs to help transfer clients from sheltered workshops into mainstream employment. That line item was initially funded with $1 million and was raised to $3 million the following year.

For Fiscal 2017, current Governor Charlie Baker, with the support of the DDS corporate providers, had proposed boosting the job development line item to $7.6 million; but the Legislature wouldn’t agree to the higher funding.

As of Fiscal 2018, the job development line item was eliminated and all funding for those efforts was transferred to the overall DDS Community Based Day and Work line item. It would seem the case needs to be made that additional funding is now needed for the day and work line item to fill the gap in work opportunity programs.

The solution needs to be comprehensive

Robin Frechette, an aide to Representative Brian Ashe, who filed H. 4541 on Govoni’s behalf, said she believes the Children and Families Committee co-chairs and other committee members “understand there is a gap in services to a particular group of individuals who are not able to work out in the community, and it needs to be addressed.”

But Frechette expressed a concern that simply having an ombudsman direct individuals whose day programs don’t offer work opportunities to different day programs that do offer those opportunities could be disruptive to those individuals. She also said she was concerned that there may be few such programs available in the western part of the state where Barbara Govoni and her son live.

Earlier this week, we sent email queries to both the Children and Families Committee co-chairs and DDS to try to find out more about the proposals under consideration.

We have asked for records from DDS on the number of work opportunity programs that currently exist in DDS-funded, community-based day programs, and the number of work opportunity programs that DDS plans to establish.

We are also asking for the number of DDS clients who have been placed in “integrated employment” or mainstream workforce jobs and the number of DDS clients in community-based day programs since Fiscal 2014.

And we have asked DDS for its assessment as to whether there is a problem in providing suitable work opportunities for people in the DDS system who desire it, and whether some DDS clients are unable to function in mainstream work sites.

In addition, we’ve asked the co-chairs of the Children and Families Committee what the committee’s specific objections to H. 4541 were.

Despite the rejection of H. 4541, the opportunity remains for state legislators and policy makers to address the critical work opportunity problem facing developmentally disabled people across the state in an effective way. We hope those legislators and policy makers will make a serious commitment to finding a workable solution; but we know from experience that deeds will be more important than words in that regard.