Archive

DDS license staff didn’t appear to notice problems mounting for resident at group home

Timothy Cheeks is a 41-year-old man with Down syndrome who lives in East Longmeadow in a group home managed by the Center for Human Development (CHD), a corporate provider to the Department of Developmental Services.

Since 2017, Tim’s foster mother and co-guardian, Mary Phaneuf, has dealt with a string of problems with Tim’s care at the residence including:

- A lack of proper medical care for Tim, including no documented visits to a primary care physician or dentist for seven years;

- No documented visits to a cardiologist for six years despite Tim’s having been born with a congenital heart defect;

- A failure to treat Tim for two years for back pain and a degenerative back problem, and to fill a prescription for pain medication for him;

- A failure to ensure that Tim was receiving Social Security benefits for at least two years;

- The unexplained removal of Tim from his day program run by the Work Opportunity Center (WOC) in Agawam without informing Mary of that fact; and

- The diversion of food stamp benefits for Tim and at least one other resident of a CHD group home

Despite the seriousness of those issues, an online June 2017 DDS licensure inspection report for CHD on the department’s website does not mention those or similar problems in the agency’s group homes. The licensure report recommended deferring a new two-year license for CHD, but for generally worded reasons such as “medication treatments plans must address all required elements,” and “individuals’ funds and expenditures must be fully tracked.”

There was no indication on the DDS provider licensure report website whether a recommended follow-up review of the provider occurred or what the result was.

COFAR has reached out to DDS and CHD for comment. In an email sent this past Tuesday (July 9) to DDS Commissioner Jane Ryder, I asked whether DDS’s licensure staff takes abuse complaints and investigations into account in drafting licensure reports concerning providers.

In a separate email the same day to CHD President and CEO James Goodwin, I asked whether Goodwin believes his agency has sufficient policies and practices in place to prevent the types of problems Mary Phaneuf is alleging or whether such policies and practices are needed. I also asked whether CHD has policies both to ensure communication with family members and guardians who raise concerns about care, and to ensure that action will be taken to address those concerns.

To date, I have not heard back either from Commissioner Ryder or from Goodwin.

Tim Cheeks with his foster sister Nicole Phaneuf Sweeney

Based on email correspondence between Mary Phaneuf and the former CHD manager of Tim’s group home, it appears that his East Longmeadow residence was inspected in 2017 as part of a two-year, DDS licensure process.

In June, DDS issued a resolution letter in response to a complaint filed by Mary with the Disabled Persons Protection Commission (DPPC). The complaint alleged that Tim had been neglected medically and that his SSI had improperly been allowed to lapse.

The DDS resolution letter also concerned a separate complaint filed by an anonymous reporter that the then house manager had misappropriated food stamp benefits for Tim and another resident.

The DDS resolution letter asked CHD to provide an accounting of Tim’s health care and that of the other resident for the past four years as well as an accounting for $2,000 in food stamp benefits that were allegedly taken from Tim and the other resident.

The DPPC had referred Mary’s complaint to DDS and apparently referred the complaint about the food stamps to the Hampden County District Attorney.

The DDS resolution letter did not dispute any of the problems Mary raised, but said an investigator had concluded that none of the problems constituted a risk of serious harm to Tim. Mary disagrees with that assessment, and has filed an appeal of the resolution letter.

Mary said she wants the public to know about the ongoing issues with her son’s care, and about her frustration in getting DDS and the provider to react to them and provide her with answers to her questions. She would like to see her information investigated by the state Attorney General’s Office, which COFAR has previously reached out to in an effort to persuade the AG to focus on care in the DDS private provider system.

Family had implicitly trusted the system

Mary said that prior to 2017, when she discovered by accident that Tim had been removed without her knowledge from his day program by the then manager of his group home, she had implicitly trusted the system. She thought, for instance, that the group home staff was regularly taking him to doctors’ appointments, particularly given that such visits were part of his care plan or Individual Support Plan (ISP).

When she found out, however, that he had been removed from his day program, she began to question everything the provider staff did or said. She was later to discover, for instance, that while Tim’s 2018 ISP stated that he had been to a dentist in September of that year and a doctor in October, CHD was unable to provide any documentation to back up those claimed visits. She now doubts that many, if any, of those visits actually occurred.

Adopted as a foster child

Tim first came to live with Mary and her family in 1981 as a foster child when he was three years old. At 22, when he became eligible for DDS services, he moved into a group home, and Mary became his co-guardian along with Tim’s birth mother. However, Tim’s birth mother has not been in contact with him, and Mary said she was told by DDS that the birth mother subsequently resigned as co-guardian.

Last year, one of Mary’s daughters, Jessica Szczepanek, became Tim’s health care proxy. Mary would like to make Jessica Tim’s co-guardian.

A 2017 DDS licensure report for CHD describes the provider as “a large, multifaceted organization,” and states that CHD operates throughout western Massachusetts as well as Connecticut.

Untreated back pain

Mary said Tim has complained of severe back pain since 2017; but after being assured by the then CHD house manager that he had been seen by a doctor who suggested it was just a posture problem, Mary discovered that he was sleeping on a “very old” futon mattress without a box spring to support it.

Additionally, she said, she discovered that he was sleeping several nights per week at another CHD residence in Wilbraham, on the Springfield line, where he had to sleep on a couch or the floor. She said she requested that CHD provide him with a proper mattress and box spring, and either purchase a bed for him at the other residence, or stop taking him there overnight.

Shortly after that, she said, she received a statement in writing from the house manager that she had purchased new memory-foam mattresses for Tim for both the East Longmeadow and Wilbraham residences.

But Tim’s back problems continued. And after visiting his East Longmeadow residence in January, Jessica went into his bedroom to look at his mattress that the house manager said she bought for him. There was not a memory foam mattress or box spring in his room, she said. Instead, he still had a futon mattress, and the tag on the mattress was so old that the letters were not legible.

No documented doctor’s appointments for seven years

In a letter sent in January to DDS Area Director Dan Donnermeyer, Mary said that she and Jessica were told the previous fall that a doctor’s appointment had been scheduled for Tim, but that the appointment kept getting rescheduled by the group home management.

In an email to COFAR, Jessica stated that during an ISP meeting last October, the then house manager had told her a physical for Tim had been scheduled for the following month of November. But in November, the house manager said the appointment had been rescheduled by the doctor’s office to late December.

Then, the day before the scheduled December doctor’s visit, the house manager told Jessica there had been “a miscommunication,” and Tim’s appointment had been moved to March 2019.

Jessica then called the doctor’s office directly. The receptionist confirmed that Tim did indeed have an appointment scheduled for March 2019, but that the appointment had only been made one day prior to her call on December 21, and that it was a new-patient visit because Tim had never been seen at that office.

At that point, Jessica wrote, she asked that CHD in December to provide her with documentation of Tim’s last visit to a primary care physician, as well as his last visit to his cardiologist, who he is supposed to be seeing annually for his congenital heart defect.

Mary provided us with CHD’s documentation of a visit to a Dr. Masih Farooqui in Wilbraham in January 2011, which she said was the most recent doctor’s visit that CHD was able to document. She said the most recent visit to a cardiologist for which CHD provided documentation was in 2012.

Despite that, Tim’s ISP documents, which are dated October 2018, contain a claim that his last physical was in September 2018. The 2018 ISP also lists the name of Dr. Farooqui as Tim’s primary care physician. Mary believes the visits claimed in the ISP never occurred.

The 2018 ISP also listed Dr. Farooqui as practicing at the 77 Boylston Street, Springfield, address of Hampden County Physician Associates. COFAR confirmed, however, that Hampden County Physician Associates no longer exists, and that Dr. Farooqui is now on the oncology staff of the Mercy Medical Center in Springfield.

COFAR was unable to reach Dr. Farooqui to confirm the year that he left that primary care practice.

Back pain prescription not filled

Mary said that on January 14 of this year, Jessica brought Tim to an Urgent Care clinic after CHD contacted her to report that Tim was continuing to experience severe back pain. She said she subsequently learned that group home staff had taken Tim to the same clinic a couple of weeks before at the end of December without her knowledge.

Mary said that after doing X-rays at the January Urgent Care visit, the doctor told Jessica that Tim had deterioration of muscle between vertebrae in his back, and that the pain he was experiencing could have been alleviated with physical therapy in 2017 when he first began complaining of back pain.

Mary added that during the previous Urgent Care visit in December, which was also for back pain, Tim was given medication and was prescribed a muscle relaxant. However, she said, CHD later informed her that the manager on duty at the group home never had the prescription filled. This resulted in continuing back pain and spasms for Tim.

Meanwhile, Jessica found out at the January Urgent Care appointment that Tim’s Mass Health coverage had been allowed to lapse for the past two years and that his Massachusetts state ID had also lapsed.

Removal from day program

In May 2017, Mary discovered that Tim had been removed from his day program at WOC without her knowledge or consent and in violation of his ISP. She said she also learned that Tim had been left alone in his group home during the day for the previous two months.

In a lengthy letter of explanation to Mary, dated in June 11, 2017, the then group home manager acknowledged that she had removed Tim from the day program, and apologized for “…my failure to talk with you and get your permission/input/opinion…”

The group home manager’s letter stated that after a sheltered workshop program at WOC was terminated (along with all remaining sheltered workshops in the state as of 2016), the manager found that there was little for Tim to do at WOC. She said she then organized a series of other activities for Tim and planned to enroll him in a “wrap-around” program approved at CHD to replace the WOC program.

Mary responded to the group home manager in an email, saying that she wasn’t taking issue with the reasons the manager had listed in her letter for removing Tim from his day program, but with the fact that she had done it without Mary’s knowledge or consent.

Mary also told DDS that she was later told by a CHD supervisor that the supervisor was unaware Tim had been removed from the WOC program, and that CHD did not have a replacement wrap-around day program as the former group home manager had claimed.

Mary added that, “no one from CHD can tell me where Tim was and who he was with for those two months” during which he was removed from the WOC day program.

Not receiving Social Security funds

In March of this year, Mary discovered that Tim had not received his Supplemental Social Security Income (SSI) since 2017. The federal SSI funds were supposed to be sent to his account managed by the group home. The funding had lapsed due to CHD’s failure to update the Social Security Administration with current information about Tim.

For two years, Mary said, the group home did not receive Tim’s monthly SSI payment of $670 from which Tim was supposed to receive a $100 monthly stipend for his needs. The missed funding over the two years totaled $2,400 that Tim needed for items such as underwear, socks, pants, shorts, sneakers, and a spare set of sheets.

DPPC referred to DDS, which found no risk of serious harm

In March, Mary filed a complaint with the DPPC alleging both neglect and financial abuse in Tim’s CHD group home. Her complaint noted that Tim had not received SSI benefits for at least two years and that he had not been seen by a doctor and had been medically neglected for at least seven years.

A separate complaint from an anonymous reporter stated that $2,000 in clients’ food stamp benefits had been taken from the two CHD group homes in East Longmeadow and Wilbraham. Both complaints appear to have been referred by the DPPC to DDS. The DDS resolution letter, dated June 7, stated that the group home manager had resigned from the group home.

The resolution letter also concluded that there was no indication of serious risk of harm to Tim. However, the letter stated that CHD had been required to respond within 30 days concerning:

- Medical appointments that have not occurred as recommended in the provider’s residences.

- Oversight that exists to ensure proper medical care in those residences.

- An accounting of food stamps taken from group home residents.

Mary filed for reconsideration of the DDS letter, disputing the finding that Tim was not at risk. For years, she noted, he was denied medical attention to monitor a hole in his heart. He was further denied treatment from 2017 to 2019 for his back pain despite having been recently diagnosed with a degenerative back disk.

Mary also contended that Tim’s loss of two years of SSI income had caused him emotional distress due to a shortage of clothing, and that he is due back payment from CHD of at least $2,400.

Mary argued that CHD needs an individual to oversee and manage all Social Security representative payee duties, and needs to ensure renewal of all MassHealth and state IDs for all clients. She further called for a review of licensing of DDS group homes. “How could seven years of missed medical and dental appointments go unnoticed?” she asked.

DDS licensure report doesn’t show any serious problems

DDS most recent online licensure report for CHD, which is dated June 2017, did not note any issues with medical care in the CHD’s residential facilities except to state that medical plans for two residents “did not fully address all required elements.”

The licensure report stated that “the vast majority of individuals in the survey sample were supported to receive timely annual physical and dental examinations, attend appointments with specialists, and receive preventive screenings as recommended by their physicians.”

The licensure report stated that audits had been completed at six 24-hour CHD residential locations, but did not say how many residential locations the provider has in total.

In her June 2017 letter to Mary, the former house manager indicated that Tim’s home was going to be inspected as part of the DDS licensure process. Her letter stated:

…in addition to my normal responsibilities I have been preparing for our licensing process (kind of like an audit) which is incredibly stressful. I was chosen mid May…both of my houses…which prompted me to work 16-hour days for weeks and try to make sure everyone still was busy, happy and having a good life.

DDS has not provided answers to Mary’s questions

Mary said that to date, her questions to DDS about Tim’s care and how his group home was able to be relicensed have gone unanswered. She said that during a May meeting to discuss Tim’s ISP, DDS and provider officials declined to discuss the many issues that she had raised.

“They only wanted to talk about correcting the ISP,” she said. “They all apologized (for the problems), but said ‘all we can do is move forward.'”

But while the officials said the former group home manager had resigned and a new manager was hired, Mary said that new manager quit in the beginning of May, telling her he was not receiving adequate support from the provider or DDS.

It isn’t surprising that DDS doesn’t want to talk about what has gone wrong in Tim’s group home for the past several years. It’s always much easier to say “let’s look forward.” But that is a prescription for continuing to repeat the mistakes of the past, and is, in fact, a tacit acknowledgement that the Department isn’t serious about addressing those problems.

We think the Attorney General’s Office needs to investigate this case and others like it as part of an overall investigation of the DDS group home system. After we met with staff of the AG in May, those officials expressed interest in undertaking such an investigation.

The Legislature’s Children, Families, and Persons with Disabilities Committee, has also done little or nothing that we know of to date to address or examine these issues. We have not heard of any results from two informational hearings that the Children and Families Committee held last year on abuse and neglect in the DDS system.

Massachusetts is a leader on many public policy fronts, but when it comes to care of the developmentally disabled, this state has a lot of catching up to do.

The late Judge Joseph L. Tauro honored at memorial service

The late United States District Court Judge Joseph L. Tauro, who paved the way for improved care for thousands of persons with developmental disabilities in Massachusetts, was honored on June 7 in a memorial service at the Moakley federal courthouse in Boston.

From 1972 through 1993, Judge Tauro oversaw Ricci v. Okin, a combined class-action lawsuit first brought by the late activist Benjamin Ricci over the conditions at the Belchertown State School. The lawsuit resulted in a consent decree that included the then Belchertown, Fernald, Wrentham, Dever, Monson, and Templeton state schools.

![]()

Tauro, who died in November at the age of 87, had visited Belchertown and the other Massachusetts facilities in the early 1970s to observe the conditions first hand. He noted two decades later in his 1993 disengagement order from the consent decree that the legal process had resulted in major capital and staffing improvements to the facilities and a program of community placements.

Together, those improvements and placements had “taken people with mental retardation from the snake pit, human warehouse environment of two decades ago, to the point where Massachusetts now has a system of care and habilitation that is probably second to none anywhere in the world,” Tauro wrote.

Among those attending the June 7 memorial service were former Governor Michael Dukakis, who signed the consent decree in 1975 on behalf of the State of Massachusetts, and Beryl Cohen, the original attorney for the plaintiffs.

Speakers at the June 7 service included U.S. Supreme Court Associate Justice Stephen G. Breyer, Senior U.S. District Judge Michael A. Ponsor, Governor Dukakis, and Major League Baseball Commissioner Robert D. Manfred Jr. Manfred, an attorney, clerked for Tauro after graduating from law school.

Also attending the service were Ed and Gail Orzechowski, advocates for persons with developmental disabilities. Ed Orzechowski’s 2016 book, You’ll Like it Here, chronicled the life of the late Donald Vitkus, a survivor of the Belchertown school.

In March, as Ed Orzechowski received the 2019 Dr. Benjamin Ricci Commemorative award from the Department of Developmental Services, he credited three men with improving the lives of persons with developmental disabilities in Massachusetts — Benjamin Ricci, Beryl Cohen, and Judge Tauro.

Ed Orzechowski (left) with former Massachusetts Governor Michael Dukakis, who signed the 1975 consent decree in the landmark Ricci v. Okin lawsuit overseen by Judge Tauro.

Gail Orzechowski, an advocate for the developmentally disabled (left), with Beryl Cohen, the attorney for the plaintiffs in the 1972 class action lawsuit, Ricci v. Okin. Gail’s sister, Carol, is a former resident of the Belchertown School.

A written remembrance of Judge Tauro in the memorial service program.

COFAR asks state attorney general to take a more active role in protecting the developmentally disabled

COFAR members met last week with officials in the state Attorney General’s Office to raise concerns about an apparent lack of focus by the state’s chief law enforcement agency on abuse and neglect of persons with developmental and other disabilities.

While Attorney General Maura Healey’s office has lately taken an active role in scrutinizing and penalizing operators of nursing homes that provide substandard care to elderly residents of those facilities, the same cannot be said of her office when it comes to investigating corporate providers of group homes for the developmentally disabled.

In March, Healey announced a series of settlements totaling $540,000 with seven nursing home operators for violations of standards of care and conditions in those facilities. In light of the attorney general’s actions and the substantial media coverage that resulted from them, COFAR asked Healey’s office for records of similar fines, settlements or penalties levied against Department of Developmental Services providers from Fiscal 2015 to the present.

In response, the AG provided records of just two cases in which penalties were imposed on DDS providers. In one case in 2017, a provider, the Cooperative for Human Services, Inc., was required by the AG to pay $19,000 in restitution to employees who had been denied overtime payments, and to pay a $4,000 fine to the state.

In the second case in 2018, Triangle, Inc. was required to donate $123,500 to charities for having paid less than the minimum wage to participants in a former sheltered workshop, without having a proper minimum wage waiver. The provider was also required to pay $6,500 to the AG’s Office to cover administrative costs.

So, that’s seven actions taken by the AG totaling more than half a million dollars against nursing home providers in just one month, versus two actions totaling $153,000 taken against DDS providers in the past five years.

Moreover, the larger of the two actions against the DDS providers was for paying subminimum wages to sheltered workshop participants — something that is seen as a problem only by opponents of sheltered workshops themselves.

As we’ve said many times, we see the real wage problem as the failure to pay adequate compensation to direct-care workers in the DDS system. That is an issue that the AG should be investigating, along with the excessive salaries paid in many cases to provider executives.

Investigating abuse and neglect

As for investigating abuse and neglect in the DDS system, the AG appears to have done nothing at least since Fiscal 2015. (We had originally asked for a list of penalties and other actions taken against DDS and its providers going back to Fiscal 2000. The AG responded that that request was overly broad in time and scope. As a result, we narrowed the request to DDS providers since Fiscal 2015.)

Certainly, the AG’s Office doesn’t present the only option for oversight of the DDS system. The Disabled Persons Protection Commission (DPPC) might be viewed as the most logical state agency to investigate abuse and neglect. That agency received more than 11,800 calls alleging abuse in Fiscal 2018 — a 74% increase from Fiscal 2010.

But with only four investigators on its staff, the DPPC is unable to investigate more than a tiny fraction of those calls, and must refer the vast majority of them to the Departments of Developmental Services and Mental Health, and the Massachusetts Rehabilitation Commission. As we have noted, those agencies face a conflict of interest in investigating abuse and neglect within their own systems.

The state Legislature should also be exercising investigative oversight of the DDS system; but the last major report from a legislative committee on abuse and neglect in facilities run by DDS and its providers was done in the 1990s.

Partly under prodding from COFAR, the Children, Families, and Persons with Disabilities Committee did hold two informational hearings last year on abuse and neglect of DDS clients. But it is unclear that the Committee intends to follow up on those hearings or even whether the hearings were, or are, part of a larger review.

The Children and Families Committee has never responded to questions from COFAR about the scope of its review, if any, of DDS. On Monday, I sent yet another email to the chief of staff of Representative Kay Khan, the House chair of the committee, asking what the status currently is of the committee’s review, and whether any additional hearings are planned. I haven’t yet received a response to that message.

AG officials acknowledge they could do more

In last week’s meeting with the AG officials, COFAR President Tom Frain, who called in; Vice President Anna Eves, and I raised concerns about the general lack of oversight of the privatization of care of the developmentally disabled in the state, and the high level of abuse and neglect as well as financial mismanagement in the system.

The three officials from Healey’s office — Jonathan Miller, chief of public protection and advocacy; Mary Beckman, chief of healthcare and fair competition; and Abigail Taylor, assistant attorney general for child and youth protection — acknowledged that the AG hasn’t done much in recent years in terms of oversight of the DDS system; but they said there may be opportunities for them to do more. Beckman said DDS clients fit within the AG’s purview, which is to protect vulnerable populations.

While none of the three officials were specific about what the AG could or might do, Miller talked about looking at “potential tools in our toolkit.”

The AG’s dual role

Beckman acknowledged that the AG’s Office is hampered in its oversight efforts by its dual roles as both a law enforcement and investigative agency, and as the state’s lawyer.

In fact, as the state’s defense attorney, the AG has consistently taken the state’s side in disputes since 1990’s over the closures of DDS state-run developmental centers and the expansion of the privatized group home system.

Nevertheless, the AG has penalized DDS providers, at least in the two instances cited above, so it clearly has the authority to do so. The key will be whether there is any follow-up by the AG’s Office to the general statements made in last week’s meeting with us.

It is unfortunate that despite the many state agencies with the authority and responsibility to investigate the care and conditions of people with developmental and other disabilities in Massachusetts, those persons appear to have fallen through the cracks in that system.

Somehow that large collection of institutional resources has not been enough to get the job done. In the case of the AG’s Office, we think the resources have so far been misdirected. We hope the Office will correct that.

DPPC’s public presentation of data on abuse is unclear

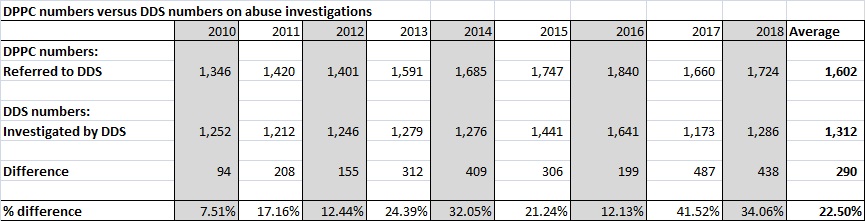

After a lengthy series of inquiries from COFAR, the state Disabled Persons Protection Commission (DPPC) has acknowledged that data in its annual reports on abuse in Massachusetts do not necessarily reflect the actual number of cases that it investigates or refers for investigation.

In letters in response to an April 12 order by the state’s public records supervisor to clarify to COFAR how the DPPC reports its data, a DPPC official said that the numbers listed in the DPPC’s annual reports of both “abuse reports” and “investigations” are not necessarily based on separate occurrences of alleged abuse. Those numbers are based instead on the number of calls or “intakes” that the DPPC receives from witnesses or other reporters.

As a result, the DPPC’s data “may be “inflated” because the agency’s “current method of data extraction can produce duplications when multiple intakes are received on the same incident,” according to Andrew Levrault, the DPPC’s assistant general counsel. Levrault said the agency’s database was “undergoing a redesign process, and this is one of the features we are hoping to improve.”

Levrault also stated in an email that the DPPC’s data may be “deflated” in some other instances.

The DPPC undertakes investigations of alleged abuse and neglect of adults under 60 with disabilities in Massachusetts, and supervises additional cases that it refers for investigation to the Departments of Developmental Services (DDS) and Mental Health (DMH) and to the Massachusetts Rehabilitation Commission (MRC). As such, the DPPC’s data are relied on by policymakers, researchers, journalists, and others as important indicators of the quality of life of persons with disabilities.

In light of the critical role that the DPPC plays, it is vital that data and other information that the agency publicly provides about the care and conditions of persons with disabilities be accurate and presented in a clear and straightforward way.

Levrault said that in contrast to the DPPC, DDS, to which the DPPC refers most of its cases for investigation, does report data based on the actual number of cases it investigates.

The differences between the DPPC and DDS in reporting abuse data make it difficult to compare that data, not only among agencies in Massachusetts, but potentially between Massachusetts and other states. COFAR has been attempting to analyze aggregate data on abuse and abuse investigations done by the DPPC, DDS, and other agencies.

The DPPC’s most recent online annual report for Fiscal Year 2017 states that the agency received 11,395 “abuse reports” that year, and that of that number, 2,571 “investigations” were assigned to investigators from the DPPC, DDS, DMH, and the MRC.

In his May 1 letter, Levrault stated that:

…the 2,571 investigations listed in the Fiscal Year 2017 Annual Report specifically refers to investigations of 2,571 intakes.

Levrault stated in the email that a single intake may refer to one or more occurrences of alleged abuse, or conversely, that “multiple intakes” may refer to a single occurrence of alleged abuse.

As a result, it appears that while the DPPC annual report listed 2,571 “investigations” in Fiscal 2017, it is unlikely that that number represents the number of investigations that were actually undertaken by the DPPC and by DDS, DMH, and the MRC. Similarly, the 11,395 abuse reports listed in the annual report for that year may or may not represent the actual number of alleged occurrences of abuse that were reported to the DPPC.

In a comparison of data from both the DPPC and DDS, COFAR found that the number of abuse intake calls referred by the DPPC to DDS for investigation each year from Fiscal Year 2010 to 2018 was, on average, 22.5% higher than the number of cases that DDS reported investigating. (See chart below created from data from both agencies.)

Those differences appear to be due to the differences in the ways that the DPPC and DDS report the data.

The accuracy of the DPPC’s data reporting is certainly a problem that can be corrected if and when the agency redesigns its database. It raises a question, however, as to why the DPPC has not made it clear in its annual reports as to what the data reported in them actually represents.

Yet, we have already seen that the DPPC is highly resistant to public disclosure of its investigative reports, and is pushing for legislation that would wrap a tighter cloak of secrecy around its records.

In failing to be clear about the meaning of its published data, the DPPC has not been transparent or straightforward about the scope and nature of the problem of abuse and neglect in Massachusetts.

The DPPC is the only independent agency available when family members or others discover abuse and neglect in the DDS system. Without the DPPC, the best option for reporters of abuse would be to dial 911. Yet the DPPC is an agency that needs to place a higher value than it currently does on the public’s right to know.

Legislators and the media should be concerned about secrecy in investigations of abuse of persons with disabilities

A bill in the state Legislature, which would draw an ever-tighter cloak of secrecy around investigative reports on abuse and neglect of persons with disabilities in Massachusetts (H.117), appears to be going relatively unnoticed on Beacon Hill and by the media.

Section 17 of the bill would effectively exempt all investigative reports and records of the Disabled Persons Protection Commission (DPPC) from public disclosure. Under the section, the DPPC’s records could be kept entirely secret even if all personal information in them were redacted.

At a certain point, laws and other initiatives that are ostensibly enacted or undertaken to protect privacy cross the line into secrecy and provide a curtain for agencies to hide behind. That is what we think is happening with Section 17 of this bill.

The DPPC is the state’s only independent agency charged with investigating allegations of abuse and neglect of adults under the age of 60 with developmental and other disabilities. Without access to the agency’s investigative reports, the public will have much less understanding, not only of the scope and nature of the problem of abuse and neglect, but what the DPPC and other agencies are doing about it.

Overall, H.117 and its counterpart in the Senate (S.53 ) propose making a number of changes to the DPPC’s enabling statute that seem helpful, such as replacing the term “disabled person,” with “person with a disability.” That latter term avoids the stigma associated with describing an individual totally in terms of their disability.

COFAR member Richard Buckley (left) and Vice President Anna Eves testify Tuesday at the State House about abuse and neglect of the developmentally disabled. At the hearing, COFAR offered testimony against proposed DPPC secrecy language in Section 17 of H.117.

However, Section 17 is not at all innocent, in our view. It would add language to the DPPC’s enabling statute stating that the agency’s records containing confidential or personal data “shall not be public records.” (my emphasis)

That proposed language is not needed to protect the personal privacy of victims of abuse and neglect or others involved in those investigations. The DPPC’s enabling statute currently states that the DPPC should disclose “as little personally identifiable information as possible.” That language gives the DPPC the discretion to protect the privacy of all parties involved.

The presumption of the state’s Public Records law is that all state governmental records are public documents unless they are explicitly exempted from disclosure by statute, or they fall under an exemption to the Public Records law itself.

At a legislative hearing this past Tuesday on H.117 and other bills concerning abuse of persons with disabilities, DPPC Executive Director Nancy Alterio touted the anti-stigmatizing aspects of H.117, but did not mention Section 17. Both Anna Eves, COFAR’s vice president, and I testified before the Children, Families, and Persons with Disabilities Committee against the section.

The committee members didn’t ask us any questions about our objection. We may have caught them by surprise about it.

The House and Senate versions of the bill were filed by Representative Sean Garballey and Senator John Keenan.

In February, Garballey got back to me and said he wasn’t aware of the implications of the Section 17, and would ask the DPPC about it. He said he agreed with us that the enabling statute should not completely restrict the disclosure of the DPPC’s records.

The chief of staff for Sen. Keenan was more noncommittal about the bill, but also said she would look into and ask about our concerns.

The mainstream media don’t seem to be paying attention this year

On March 21, I emailed Boston Globe Editor Brian McGrory, laying out our concerns in detail and asking whether the Globe might take a position against the language in Section 17. To date, McGrory has not responded to that or to a subsequent email I sent about the bill on April 5 and again on April 8 to The Globe and other news organizations around the state.

The New England First Amendment Coalition published our email to mainstream media outlets on its blogsite on April 8. But we have gotten little or no response from the rest of the media either.

Our media list includes current editors and other staff on 24 newspapers, including the Globe and Herald; major chains such as the North of Boston Media Group; the Associated Press, the State House News Service; CommonWealth Magazine; major Boston television news outlets; and NPR radio affiliates WBUR and WGBH.

The Globe in the past has taken strong stances in favor of the public disclosure of state records. In 2015, the paper organized coordinated editorials among several media outlets criticizing the state’s Public Records supervisor for rulings allowing the withholding of records from public disclosure by state agencies.

The Globe’s 2015 editorial maintained that the state’s criminal-records law, in particular, “was never intended to open up a memory hole to conceal unflattering information about the police.”

That is similar to the argument we have made in seeking to obtain investigative records from the DPPC. And now, Section 17 would make that cloak of secrecy even more opaque.

DPPC heading in the direction of the Elder Affairs office

Unfortunately, with the introduction of Section 17 in H.117, it appears that the DPPC is seeking to emulate the Executive Office of Elder Affairs (EOEA), which investigates abuse and neglect of persons 60 and older. The EOEA’s enabling statute does state that the agency’s records are not public.

On its website,the DPPC states that the reason for the non-public records provision in H.117 is to make the DPPC’s enabling statute conform to the EOEA’s statute in order to give persons with developmental disabilities “the same safeguards provided for the records of elders.” (Please note that the bill numbers on the DPPC website appear to be from the prior legislative session.)

But that only raises further concerns for us about the potential secrecy of the EOEA’s records.

As noted, the enabling statute of the EOEA, M.G.L. c. 19A, s. 23, explicitly states that departmental records containing confidential information are not public. The EOEA statute goes even further, giving the Elder Affairs Department the authority to actually destroy investigative records about abuse allegations if the department finds that the allegations are unsubstantiated. This seems to us to be bad law and not one that the DPPC should be emulating.

The DPPC’s regulations go further than the enabling statute in exempting records from disclosure

While the DPPC’s regulations explicitly state that the DPPC’s records are not public , the agency’s enabling statute, as noted, says only that the DPPC should disclose “as little personally identifiable information as possible.”

The DPPC’s regulations go further in shielding the agency’s records from public disclosure than does the enabling statute, and we think the regulations should therefore be changed to conform to the enabling statute. H.117, however, would do the opposite by making the statute conform to the regulations.

We hope The Globe and other media outlets in Massachusetts wake up to the threat this bill poses to transparency in state government. The DPPC receives tens of thousands of allegations of abuse and neglect each year, and “screens in” several thousand of those for investigation.

It is already extremely difficult to obtain those records from the DPPC even in redacted form. H.117 would make it virtually impossible to obtain those records, and would move state government that much further away from operating with openness and transparency.

DPPC ordered to clarify its abuse reporting system following data inflation admission

In the wake of an acknowledgement by the Disabled Persons Protection Commission (DPPC) that some of the data it had provided COFAR on abuse may be inflated, the state’s public records supervisor has ordered the agency to clarify the nature of the data it publishes.

The April 12 decision by Public Records Supervisor Rebecca Murray is in response to an appeal filed by COFAR after the DPPC stated that it was unable to provide data on the actual number of “abuse allegations” the agency receives each year and the number of such allegations that are substantiated by investigations.

In emails in March, Andrew Levrault, DPPC assistant general counsel, stated that spreadsheet data on abuse complaints and investigations, which the DPPC had previously provided to COFAR, “may be inflated.” He later stated, in a response to COFAR’s appeal, that the DPPC’s data may be “deflated” in some other instances.

Levrault said that the probable data inflation occurred because the agency does not track actual abuse allegations, but rather tracks abuse “intakes,” which are calls made to the agency. He said there may be “multiple” intake calls for each allegation, and that the DPPC is unable to “extract” the number of actual allegations that the agency receives.

Levrault’s statements appear to leave it unclear whether data listed in the DPPC’s annual reports accurately represents the number of abuse allegations or incidents that the agency is informed of or investigates. Levrault did claim in an email that the numbers in the annual reports are not inflated.

In her April 12 decision, Murray stated that while the DPPC has noted that it cannot extract data by allegation, “the DPPC did not clarify whether it could produce the data to back up the numbers DPPC uses to draft its Annual Reports.”

Murray noted that COFAR has questioned “how it is possible that DPPC is able to report the number of abuse reports and number of investigations, if it cannot extract that data from its database. I find that DPPC must clarify this.”

In an email on March 14, Levrault acknowledged deficiencies in the DPPC’s abuse tracking system. He stated that:

…our current method of data extraction can produce duplications when multiple intakes are received on the same incident. The database is undergoing a redesign process, and this is one of the features we are hoping to improve.

Later, in an April 8 response to COFAR’s records appeal, Levrault stated that when compared to the record keeping system used by the Department of Developmental Services (DDS), to which the DPPC refers many of the abuse complaints it receives:

… the DPPC’s figures may be elevated in some instances, and may be deflated in others–depending on the nature of the comparison.

Yet, when asked by COFAR, also on March 14, whether the numbers of “abuse reports” listed in the DPPC’s annual reports are therefore likely inflated, Levrault replied that the numbers in the annual reports “are not inflated. They are consistent with our long-standing statutory reporting requirements, which mandate that we report the ‘number of claims of abuse.’ (emphasis in the original)

Levrault did not explain how it could be the case that the DPPC is able to report accurate or non-inflated numbers in its annual reports if the agency is unable to track or extract data on abuse allegations, and tracks only data on intakes.

The DPPC’s most recent annual report for Fiscal Year 2017 states that the agency received 11,395 “abuse reports” that year, and that it had “screened in” 2,571 of those reports for investigation by the DPPC itself and other agencies.

The annual report stated that the same number of 2,571 “investigations” was assigned to investigators from the DPPC, the Department of Developmental Services, the Department of Mental Health, and the Massachusetts Rehabilitation Commission, and that those investigators had completed 1,866 of those investigations.

It is unclear whether the 11,395 “abuse reports” cited in the 2017 annual report is a reference to intakes or to allegations. However, given that the annual report refers to 2,571 of those 11,395 abuse reports as representing “investigations,” it would appear that the number 11,395 does refer to actual allegations.

If, however, it is the case that the spreadsheet data provided to COFAR by the DPPC is inflated, it would render that data virtually useless in attempting to determine the number of abuse allegations that agency receives and investigates each year.

However, Levrault also stated in a separate email on March 14 that:

Each intake received by the DPPC is assigned a separate case number. If the DPPC receives multiple intakes involving the same allegation and the allegation meets the DPPC’s jurisdiction, then the intakes will be combined for investigation. Moving forward, the DPPC case would then be identified by the combined intake numbers. (my emphasis)

That statement by Levrault appeared to imply that the agency does, in fact, keep documentation on the number of abuse cases that it either investigates or refers to other agencies for investigation.

As a result, COFAR asked the DPPC on March 15 for the number of abuse allegations and investigations resulting from intake reports that the DPPC had “combined for investigation.” When Attorney Levrault responded that the DPPC had no responsive records to that request, COFAR appealed the matter to the state’s Public Records Supervisor.

DDS does track abuse allegations

As noted, Levrault stated in his April 8 response to COFAR’s appeal that unlike the DPPC, DDS does have the capability of tracking individual abuse allegations or cases. The DPPC refers the majority of the abuse complaints it receives to DDS for investigation.

COFAR has previously reported that the DPPC actually has a lower abuse-allegation caseload per investigator than DDS, and that the DPPC has substantiated a higher percentage in recent years of the allegations it has investigated itself than has DDS.

In reporting those percentages, COFAR was assuming that the DPPC was consistent in reporting the number of allegations it was investigating itself, and the number of allegations that DDS was investigating.

In the past year, we have been battling with the DPPC over the transparency of the agency’s investigative policies. We think our latest appeal concerning the data the DPPC publishes underscores the need for a major review and overhaul of those policies and procedures.

Mother pushes for medical training bill after her son dies following a seizure

Maureen Shea’s son, Tommy, had just returned on June 7, 2017, from a two-week stay in a hospital to his staffed studio apartment.

Tommy, who was 33, had an intellectual disability and was subject to epileptic seizures while asleep. His bedroom was equipped with an audio and visual monitor that could alert the staff so that the staff could make sure during a seizure that Tommy didn’t roll over face-down — a position that can prevent breathing.

Maureen Shea (right) talks with COFAR Vice President Anna Eves prior to a hearing by the MDDC last week on legislative proposals this session concerning the developmentally disabled. Shea is pushing for a bill that would ensure that residential facility staff are adequately trained to use medical equipment needed by the facility residents.

Maureen and her daughters were concerned that the residential staff did not regularly check the monitor’s batteries and that they had not been adequately trained in how to position the device. But provider managers had repeatedly assured Maureen that the staff were being trained and were knowledgeable about Tommy’s medical equipment.

On June 8, 2017, Maureen received a call from the residential supervisor to come to the residence immediately. When she arrived, the police were there. They told her that Tommy had died and that he had been found face-down on his bed. The batteries in the monitor were later found to be dead.

Last week, Maureen recounted her experience at a hearing held by the Massachusetts Developmental Disabilities Council (MDDC) on bills concerning persons with developmental disabilities. The bills have been filed in the new 2019-2020 legislative session.

Maureen and her family have proposed one of those bills. It would require that when a disabled individual is discharged from a hospital to a residential facility, a licensed medical professional from the facility must review and acknowledge the full requirements of the hospital discharge plan regarding any life support or other medical equipment. The medical professional must then advise the residential staff about those requirements.

That bill (SD 1176), which was filed by Senator Patrick O’Connor, Maureen’s state senator, is one of several legislative priorities for COFAR as well. At the MDDC hearing, we presented those priority bills, including a measure to make information about care in the DDS group home system more available to the public. We’ll have more information on those bills in our next post.

Staff was required to check monitor

As of early June 2017, Tommy had spent two weeks in a hospital for treatment of chronic vomiting due to migraines. Maureen was nervous about his return to his apartment because he had had four epileptic seizures in his sleep during the year and a half he had been living there.

Tommy’s Individual Support Plan (ISP)stated in a number of places that staff would check his monitor every day, Maureen said. She and her daughters waited 11 months for the results of the autopsy, which concluded that Tommy had died of cardiac arrest with epilepsy as a contributory cause.

Maureen said that prior to Tommy’s death, she had to enlist the Disability Law Center to represent her in an effort to force the program staff provider to agree to provide a van for Tommy’s transportation with a non-smoking driver. He had life-threatening asthma.

Tommy’s case recalls that of Yianni Baglaneas

Unfortunately, the apparent failure of the group home staff in Tommy’s case to check his seizure monitor recalls the case of Yianni Baglaneas, the son of Anna Eves, now COFAR’s vice president. Yianni nearly died in April 2017 after aspirating on a piece of cake in a group home in Peabody.

An investigation by the Department of Developmental Services found that the staff of Yianni’s group home had failed to to ensure that he regularly used a portable breathing mask at night called a CPAP (continuous positive airway pressure) machine. Based on the input of a medical expert, the report concluded that the failure to use the machine was the cause of the aspiration that led to Yianni’s near-fatal respiratory failure.

Family members all-too-frequently find that they must take the lead in trying to ensure that their loved ones are safe and well cared for in the system; but when providers and the Department itself aren’t willing or able to match that diligence, the outcomes are too often tragic.

We hope the Legislature’s Children, Families, and Persons with Disabilities Committee will act favorably on Maureen’s bill and ensure that it moves toward passage. The Committee also needs to continue its investigation of the DDS system, which was begun a year ago, and which does not appear up to now to have made much progress.

Ultimately, DDS needs to cooperate fully with the legislative investigation and show it is committed to fixing the system. Passage of Maureen’s bill is one of many steps that need to be taken by the Legislature in the meantime.

New data provide more evidence that the DPPC should do all abuse investigations

New data provided by the Massachusetts Disabled Persons Protection Commission (DPPC) and the Department of Developmental Services (DDS) raise further questions about the ability of DDS, in particular, to adequately investigate cases of abuse and neglect within its system.

As such, we think the data provide yet a further reason to place all investigative resources and functions within one independent agency — the DPPC.

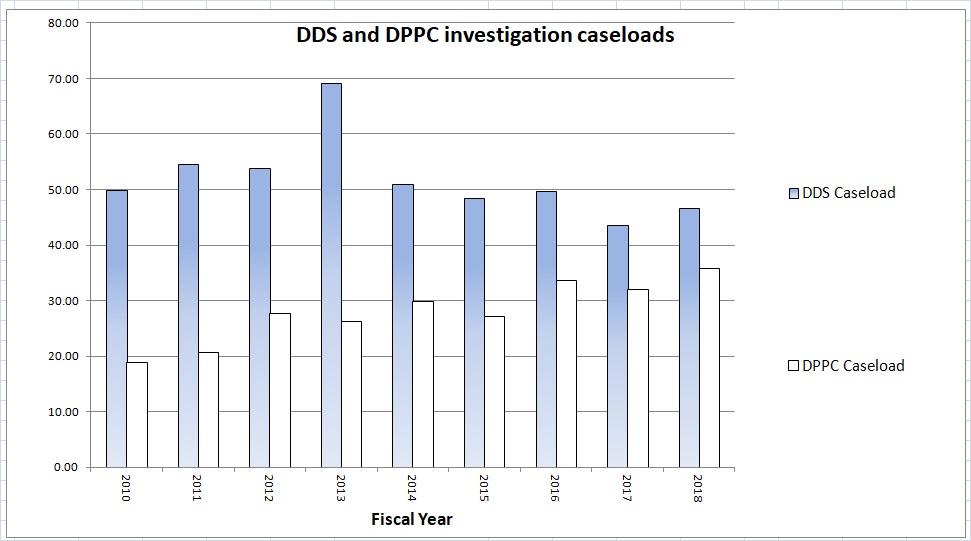

The latest data, received under Public Records Law requests to both agencies, show that not only does the DPPC have fewer abuse investigators than does DDS, but the DPPC investigators themselves appear to have lower caseloads than do their counterparts at DDS.

Yet, the DPPC is the state’s sole independent agency charged with investigating abuse and neglect of disabled adults. As we have reported, the DPPC is so poorly funded that it has to refer most of the complaints it receives to DDS and other service-providing agencies to investigate.

The caseload data comes on top of previous data we received showing that the DPPC investigators tend to find that a higher percentage of abuse allegations have merit than do their counterparts at DDS. Given the DDS caseloads are higher than the DPPC’s, it appears possible that DDS investigators aren’t able to do investigations as thoroughly DPPC investigators.

The latest data obtained from DDS and the DPPC also show that the number of substantiations of abuse allegations in general has been dropping in investigations done, particularly by DDS.

DDS’s main function is to manage and oversee care to the intellectually and developmentally disabled through a network of both state-operated and corporate provider-operated group homes and other facilities. Because of that, DDS appears to face a conflict of interest in investigating allegations of abuse and neglect in its own system.

Higher DDS caseloads

The chart we created below shows the consistently higher average caseloads that DDS investigators have had compared with the DPPC’s investigators, although the DPPC’s caseloads have been rising in recent years.

Between Fiscal 2010 and 2018, DDS’s yearly caseload has averaged 51.9 abuse investigations per investigator, while the DPPC’s average caseload has been 27.9. (DDS has employed an average of 31.4 abuse investigators each year while the DPPC has employed an average of 4.6 investigators each year in that time frame.)

Source: DPPC and DDS data

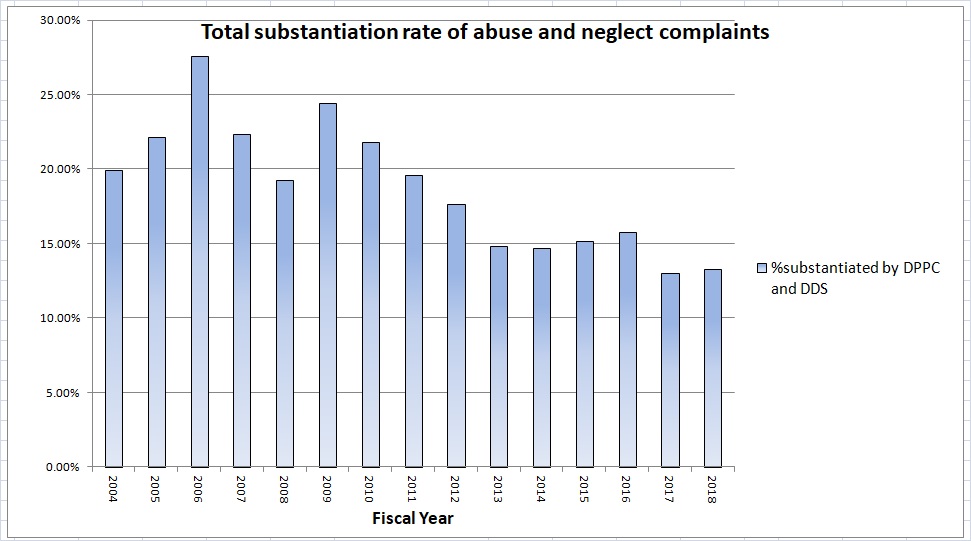

Based on the DPPC’s data, our second chart below depicts the dropping abuse substantiation rate each year for both the DPPC and DDS.

According to the data, the annual percentage of abuse allegations that have been substantiated by DDS and the DPPC dropped from a high of 28% in Fiscal 2006 to about 13% in Fiscal 2018. The conclusion we draw from this particular data is that funding to both agencies for investigations has been increasingly inadequate.

The DPPC’s higher abuse substantiation rate since Fiscal 2012

The data going back to Fiscal 2004 show that the DPPC began consistently substantiating a higher percentage of abuse allegations than DDS starting in Fiscal 2012. There were three years between Fiscal 2004 and 2011 in which DDS substantiated a higher percentage of allegations than did the DPPC.

There don’t seem to be clear reasons for either the relatively higher abuse substantiation rate by the DPPC or the dropping substantiation rate by DDS, in particular, although, as noted, one reason might be DDS’s relatively high caseloads.

The DPPC’s policy to reserve more serious cases for itself

It’s possible that the DPPC has had a higher abuse substantiation rate because the agency has tended to reserve what might be considered the most serious abuse cases to itself, and that those more serious cases would be more likely to be substantiated than would the less serious cases assigned to DDS.

At first glance, a policy document we received from the DPPC on assigning cases would seem to support that theory. The policy lists a number of instances in which the DPPC assigns more serious cases to itself provided that it has the resources to do so.

But the DPPC policy is dated 1998. There doesn’t seem to be a clear pattern of abuse substantiations from either the DPPC or DDS that lines up with the policy or its revisions in 2013 and 2016.

DDS says DPPC substantiation data misleading

In a response earlier this month to our questions, DDS maintained that the data we used from the DPPC doesn’t reflect the true abuse substantiation rates for DDS.

The DDS response included a lengthy explanation for why this is so, but the gist of the explanation seems to be that the DPPC data doesn’t account for all of the cases that DDS investigates, and that the DPPC counts the cases differently than DDS. We don’t think, however, that any such differences would affect the overall results of our analysis because we used the DPPC’s substantiation-rate data for both the DPPC and DDS, and we are assuming that the DPPC has been consistent in how it accounts for the cases investigated by both agencies.

The DDS’s conflict of interest

As we’ve stated, the data point toward the logic of having all abuse investigations done by one independent agency. The current system under which abuse investigations are done by separate agencies makes no sense, and leads at the very least to the perception that the investigations done by DDS are not thorough and cannot be relied upon.

As we reported in our January 2004 issue of The COFAR Voice, the DPPC itself issued a position statement at that time charging that DDS (then the Department of Mental Retardation) and other state agencies were “vulnerable to pressures that could compromise the integrity of their investigative findings (in abuse cases).”

Filing legislation to place in investigative resources solely within the DPPC

We will share our findings regarding the DPPC and DDS investigation data with the Legislature’s Children, Families, and Persons with Disabilities Committee. We hope these findings will concern them as much as they concern us.

We are also seeking to file legislation in the current legislative session to place all resources for abuse and neglect investigations within the DPPC, and to place all DDS provider licensure and monitoring resources within an independent state Office of Quality Assurance.

The Children and Families Committee initiated a review of the DDS system in January of 2018 and called in the DDS commissioner and DPPC executive director on two occasions last year to testify about abuse and neglect in the DDS system. Both officials insisted the system is functioning smoothly and offered no suggestions for changing it.

The families in our organization know that the system isn’t fine and it isn’t running smoothly. The Children and Families Committee, however, has not allowed those family members and guardians to testify publicly about their experience with the system.

We hope things finally begin to change in the new legislative session, which just started this month, and that the Legislature will begin to take concrete steps to protect the developmentally disabled in this state from abuse and neglect.

A clear starting point would be to give the DPPC, the state’s independent abuse investigation agency for the disabled, the necessary tools and authority to do the job.

DDS lags independent DPPC in abuse substantiations

Although the state Department of Developmental Services investigates far more abuse allegations of the developmentally disabled in Massachusetts than does the independent Disabled Persons Protection Commission (DPPC), DDS found a lower percentage of the allegations to have merit than did the DPPC between Fiscal Year 2015 and the present, data provided by the DPPC show.

While the DPPC is technically the lead state agency in investigating complaints of abuse and neglect of the disabled in the state, the agency is so poorly funded that it is forced to refer most of the complaints it receives to DDS and other agencies to investigate.

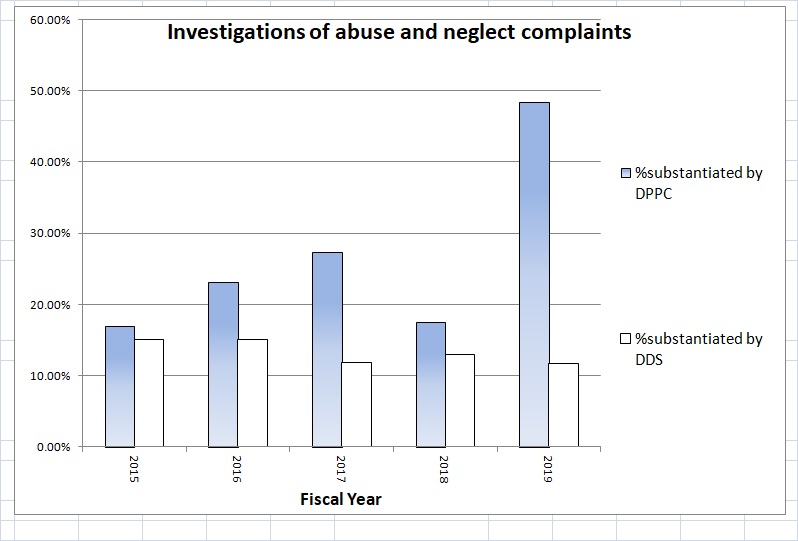

As the chart below shows, the DPPC “substantiated” an average of 22.7% of the abuse allegations that the agency itself investigated from Fiscal Year 2015 through 2019. During that same time period, DDS substantiated an average of only 13.6% of the allegations that the Department itself investigated.

The chart is based on the DPPC data, provided to COFAR under a Public Records Law request.

When allegations of abuse are substantiated, DDS and its corporate providers of care are usually required to take corrective measures, which can include providing training, changing procedures, and barring alleged abusers from further employment in the system. The DPPC has a separate State Police Detective Unit that refers some of the allegations to local district attorneys offices for separate criminal investigation and prosecution.

The DPPC, which was established in 1987 as an independent agency to investigate allegations of abuse and neglect of adults with intellectual and other disabilities, had only four investigators on its staff (not counting the State Police Unit) as of Fiscal Year 2017, according to its latest online annual report. Despite that, the agency received more than 11,000 reports of abuse of the disabled that year, according to the annual report.

According to the DPPC data, the agency itself investigated an average of only 144 abuse complaints per year between Fiscal Years 2015 and 2018, the last year for which complete data were provided. During that same period, the DPPC referred an average of 1,743 complaints per year to DDS to investigate.

But while DDS does have more investigative resources than the DPPC, DDS’s main function is to manage and oversee care to the intellectually and developmentally disabled through a network of both state-operated and corporate provider-operated group homes and other facilities. As such, DDS appears to face a conflict of interest in investigating allegations of abuse and neglect in its own system.

The DPPC data for Fiscal 2019 are only partial so the percentage of substantiated cases between the DPPC and DDS may not vary as widely as of the end of the year as they appear to do now. But there seems to be a pattern going back to Fiscal 2015 that verifies concerns we’ve raised that DDS has an incentive to downplay complaints of abuse and neglect in its own facilities, whether they are state or provider-operated.

The DPPC doesn’t appear to want to talk with us. Neither Nancy Alterio, the executive director of the agency, or anyone else there has agreed to several requests for an interview.

Apparently, very little has changed since 2004 in the relationship between the DPPC and DDS except that prior to at least that year, DPPC officials were willing to state publicly that DDS was compromised in investigating abuse within its own system.

The January 2004 issue of The COFAR Voice noted that the DPPC had issued a position statement charging that DDS (then the Department of Mental Retardation), the Department of Mental Health, and other state agencies were “vulnerable to pressures that could compromise the integrity of their investigative findings (in abuse cases).”

There have been instances, the DPPC statement noted, in which information contained in investigative reports had been altered “to absolve the service-providing agency from liability.”

The DPPC statement added that among the reasons that the DPPC should conduct abuse investigations internally were that it would lend integrity to the investigation process and would provide a “political safety valve” to other agencies, whose own investigations might otherwise be branded as “whitewashes.”

The DPPC statement even compared the investigations of abuse by service-providing agencies to the recent sex abuse scandal within the Catholic Church in which the system had “closed its eyes to its failings and attempted to protect itself by protecting the wrongdoers within it.”

Thomas J. Frain, COFAR’s president, is also quoted in the 2004 article, as saying, “DMR is dependent on these providers for services and is going to be very reluctant to sanction them for either poor service or abuse. We need an independent organization like the DPPC to do this.”

Seeking additional information

Last week, we asked the DPPC for additional data, including:

- The number of investigators employed by DDS and the DPPC to investigate complaints of abuse from Fiscal Year 2004 to the present.

- Any written agreements between the DPPC or DDS or written policies or guidelines that concern the process of determining which abuse complaints are assigned for investigation by the DPPC and which complaints are assigned for investigation by DDS.

We have also asked both the DPPC and DDS for comment on the data showing a higher percentage of substantiation of abuse complaints by the DPPC. So far, we have not heard back from either agency on that question.

And we’ve asked the DPPC whether they stand by the agency’s statement prior to 2004 that the agency should have the resources to conduct all abuse investigations internally. We’ve asked DDS as well whether they agree that the DPPC should conduct all abuse investigations.

We’ll be back here to report on the answers we get from each agency. It’s certainly possible that the DPPC and DDS will provide a reason we haven’t thought of as to why the abuse substantiation rates differ between each agency. (We would note that the overall percentage difference between 2015 and the present appears to be large enough that it is likely not due to chance alone.)

Whatever that reason given, if a reason is given, for the difference in the substantiation percentages might be, we’ll report it. But the perception of a conflict of interest remains in having the DDS investigate its own system. Thirty-one years after the creation of the DPPC, that needs to be changed.

Committee airs testimony on sexual abuse of the disabled, but offers little indication of its next steps

While members of a legislative committee heard testimony on Tuesday about sexual abuse of the developmentally disabled in Massachusetts, the state lawmakers on the committee gave little indication as to what they plan to do with the information.

COFAR was one of several organizations invited by the Children, Families, and Persons with Disabilities Committee to testify. The committee members asked no questions of any of the three members of COFAR’s panel, who testified about serious and, in one case, fatal abuse of their family members in Department of Developmental Services-funded group homes.

Tuesday’s hearing on sexual abuse in the DDS system. The committee members asked no questions of COFAR’s panel.

COFAR President Thomas Frain, Vice President Anna Eves, and COFAR member Richard Buckley also offered recommendations to the committee, including establishing a registry of caregivers found to have committed abuse of disabled persons, and potentially giving local police and district attorneys the sole authority to investigate and prosecute cases of abuse and neglect.

The hearing drew some mainstream media coverage (here and here); but, while COFAR had alerted media outlets around the state to the hearing, most of the state’s media outlets, including The Boston Globe, did not cover it.

Committee asks no questions

Following the hearing, Frain said he was glad to get the opportunity to testify, but frustrated that the members of the committee seemed to lack interest in what he and COFAR’s other panel members had to say.

“It crossed my mind, were the committee members told not to ask any questions?” Frain said. “How divorced and disengaged is the Legislature that they can hear this testimony and not even have a follow-up question about an agency they’ve voted to fund?”

The hearing was the second since January involving testimony invited by the Children and Families Committee on the Department of Developmental Services system. The general public was allowed to attend, but not permitted to testify publicly before the committee in either hearing. The committee has given no information regarding the scope of its review of DDS.

COFAR has continued to ask for information from the committee as to the full scope of its review, and whether the committee intends to produce a report at the end of that review.

COFAR panel describes abuse and neglect

On Tuesday, Richard Buckley testified about his 17-year quest for answers to his and his family’s questions about his brother’s death in a group home in West Peabody in 2001. Buckley’s developmentally disabled brother, David, had previously been sexually abused in a group home in Hamilton, and was ultimately fatally injured in the group home in West Peabody.

David Buckley received second and third degree burns to his buttocks, legs, and genital area while being showered by staff in the West Peabody residence run by the Department of Developmental Services. The temperature of the water in the residence was later measured at over 160 degrees.

David died from complications from the burns some 12 days later, yet no one was ever charged criminally in the case, and the DDS (then Department of Mental Retardation) report on the incident did not substantiate any allegations of abuse or neglect.

Richard Buckley urged the committee to take action to reform the DDS system. “If nothing is done, the next rape, assault or death, will be on you,” he said. “And we will remember that.”

Buckley also read testimony from another COFAR member, Barbara Bradley, whose 53-year-old, intellectually disabled daughter is currently living in a residence with a man who has been paid by a DDS-funded agency to be her personal care attendant. In her testimony, Bradley said the man initiated a sexual relationship with her daughter, and later brought another woman, with whom he also became sexually involved, to live in the same residence.

Anna Eves discussed the near-death of her son, Yianni Baglaneas, in April 2017, after he had aspirated on a piece of cake in a provider-operated group home. The group home staff failed to obtain proper medical care for Yianni for nearly a week after he aspirated. He was finally admitted to a hospital in critical condition and placed on a ventilator for 11 days.

DDS later concluded that seven employees of Yianni’s residential provider were at fault in the matter. Nevertheless, at least two of those employees have continued to work for the provider, Eves said.

“The systems that are in place are not working and we are failing to protect people with intellectual and developmental disabilities in Massachusetts,” Eves testified. “We have to do better.”

Eves urged the committee to support a minimum wage of $15 an hour for direct care workers, more funding for the Disabled Persons Protection Commission, and passage of “Nicky’s Law,” which would establish a registry of caregivers found to have committed abuse or neglect. Such persons would be banned from future employment in DDS-funded facilities.

Eves also noted that licensing reports on DDS residential and day program providers that she reviewed — including the provider operating her son’s group home — did not mention substantiated incidents of abuse or neglect. She said Massachusetts is falling behind a number of other states, which provide that information to families and guardians.

In his testimony, Frain also urged the committee to support more funding for the Disabled Persons Protection Commission, the state’s independent agency for investigating abuse and neglect of disabled adults. Because the agency is so grossly underfunded, he suggested that the committee consider either “fully funding” the agency or “partnering with the local police and district attorneys’ offices and let them investigate” the complaints.

Frain maintained that staffs of corporate providers, in particular, face pressure not to report complaints to the DPPC, and that the agency, in most cases, has to refer most of the complaints it receives to DDS. That is because the DPPC lacks the resources to investigate the complaints on its own.

Moreover, Frain maintained, the current investigative system is cumbersome. It can sometimes take weeks or months before either the DPPC or DDS begins investigating particular complaints, whereas police will show up in minutes and start such investigations immediately.

Frain also contended that “privatization of DDS services has been at the root of many of these problems.”

Other persons and organizations that testified Tuesday included DDS Commissioner Jane Ryder, the Arc of Massachusetts, the Massachusetts Disability Law Center, and the Massachusetts Developmental Disability Council.

COFAR is continuing to urge the Children and Families Committee to hold at least one additional hearing at which all members of the public to testify publicly before the panel. COFAR has also been trying to obtain a clear statement from the committee as to the scope of its ongoing review of the Department of Developmental Services.

For a number of years, COFAR has sought a comprehensive legislative investigation of the DDS-funded group home system, which is subject to continuing reports of abuse, neglect and inadequate financial oversight.