Archive

DDS report faults provider and charges cover-up in near-fatal, group home food aspiration case

(Update: The Essex County District Attorney’s Office confirmed this morning (October 26) that they have opened a criminal investigation into this matter.)

As The Salem News reported this morning (October 25), an investigation by the Department of Developmental Services of the near death of a developmentally disabled man who aspirated on a piece of cake in his group home concluded that seven employees of the private provider that operated the residence were at fault in the matter.

The scathing report, which is dated September 8, also stated that a high-level employee of the Beverly-based provider, Bass River, Inc., removed key records from the facility concerning the matter and instructed staff not to cooperate with the DDS investigation. The findings have reportedly led to a criminal investigation by the Essex County District Attorney’s Office.

The report was released by the Disabled Persons Protection Commission, an independent agency, which investigates abuse and neglect of disabled individuals, and which had referred the case to DDS to investigate.

In August, we first reported that the staff of the group home had failed to react for nearly a week after the 29-year-old man, Yianni Baglaneas, reportedly aspirated on a piece of birthday cake in the residence on April 9. He was admitted to Addison Gilbert Hospital in Gloucester in critical condition on April 15, and spent 11 days on a ventilator and a week in the Intensive Care Unit at Mass. General Hospital.

Aspirating or inhaling food into the lungs is a particularly serious danger among people with intellectual disabilities.

The DDS report did not identify the Bass River staff or other employees by name, but one of the individuals cited for abuse and neglect is believed to be the group home director, and another is the provider’s residential director who had authority over all of the agency’s group homes.

According to the report, the residential director acknowledged instructing staff of Yianni’s residence not to cooperate with the DDS investigation. The director also acknowledged removing records from the facility. The DDS investigator was subsequently unable to locate key records relating to Yianni’s care.

The DDS report stated that charges of abuse and mistreatment were substantiated in the case because the group home staff was negligent in failing to ensure that Yianni, who has Down Syndrome, regularly used a portable breathing mask at night called a CPAP (continuous positive airway pressure) machine. Based on the input of a medical expert, the report concluded that the failure to use the machine was the cause of the aspiration that led to Yianni’s near-fatal respiratory failure.

A group home staff member did bring Yianni to a nurse practitioner at Cape Ann Medical Center in Gloucester on April 13, four days after he aspirated on the cake. The nurse practitioner diagnosed Yianni’s condition as bronchitis and an upper-respiratory infection. She performed a nebulizer treatment on him and prescribed cough syrup and Mucinex and Robitussin, which are over-the-counter decongestants.

According to the DDS report, the nurse practitioner stated to the staff member that Yianni should be brought back if his condition worsened, but that Yianni was never brought back to the medical center.

The DDS report charged that the group home staff, including the house director, committed mistreatment for failing to ensure that Yianni received the prescribed decongestant medications. And the report charged that the house director committed mistreatment in failing to follow up on recommendations of Yianni’s day program staff on April 14 that the staff seek medical attention for him because he appeared to be very ill.

Yianni’s mother, Anna Eves, said she believes criminal charges should be filed in the case in light of the DDS report. “It’s easy for them (the provider and key staff) to abuse and neglect people in the shadows, and this needs to be brought out into the light of day,” she wrote in an email. “I have felt physically ill since reading this report and reading the absolute disregard for my son’s well being. I cannot believe I ever trusted them at all.”

The DDS report did not address the issue of possible criminal charges, but did recommend that DDS re-evaluate the group home’s license to continue to operate.

Yianni was actually taken to Addison Gilbert Hospital on April 15 by his mother, who had not seen him during the previous week. She met him at a Special Olympics track practice in Gloucester to which he had been brought by a staff member of his group home.

According to the DDS report, Yianni’s Special Olympics track coach stated that Yianni appeared to be extremely lethargic, coughing and having difficulty breathing. Yet no one from the group home informed either the coach or Yianni’s mother that Yianni was seriously ill.

That group home staff member told the investigator that Yianni had been taken to the track practice because the group home was closing for the weekend, and it did not matter how sick he was.

We do not think Yianni’s case is unique in Massachusetts. This morning, I sent an email to the House chair and Senate vice chair of the Children, Families, and Persons with Disabilities Committee, renewing a call we have made for a hearing into issues surrounding oversight of privatized human services. We have called for such hearings by the committee in the past, to no avail.

Alleged obstruction of the investigation

The DDS report described a number of instances of apparent obstruction of the DDS investigation of Yianni’s case.

According to the report, the Bass River residential director acknowledged to the investigator that she removed documents from the group home before the investigator could see them. She also acknowledged to the investigator in an initial statement that she had directed staff in the group home not to cooperate with the investigation. She later changed that statement, according to the report.

One witness told the investigator that he heard the residential director say to a staff member that “there will be consequences” if he cooperated with the investigation.

The report stated that records that could not be found or obtained by the investigator included daily and after-hours shift reports, emails from the time-frame in question, medication-related documents, Yianni’s ISP or care plan reports, and staffing schedules.

Failure to use the CPAP machine

According to the DDS report, Yianni has been diagnosed with sleep apnea, a potentially dangerous condition that is characterized by interrupted breathing during sleep.

The report concluded that seven employees of Bass River were negligent in failing to administer prescribed medication and to ensure that Yianni used his doctor-ordered CPAP machine, and that this failure directly contributed to his “serious, life-threatening medical condition.” That failure “more likely than not caused Yianni to aspirate while eating or sleeping, directly causing the aspiration pneumonia,” the report stated.

In a 180-day period between October 2016 and April, Yianni only used the CPAP mask on 36 days, or 20 percent of the time, according to the report.

The medical expert told the DDS investigator that without the nightly use of the CPAP machine, Yianni’s breathing would stop while he was sleeping, his heart rate would rise, and his red blood cell count would drop to levels that could be life threatening. In addition, this situation would have affected Yianni’s brain function negatively during his waking hours, causing him to have difficulty chewing and swallowing food and to aspirate on it.

The medical expert determined that Yianni could have either aspirated on food or fluids built up in his throat due to not using the CPAP machine. According to the expert, there is a direct link between sleep apnea and aspiration pneumonia when the apnea is not treated with a CPAP mask.

At least two Bass River employees stated that they were aware the staff were not making sure Yianni used the CPAP machine, but failed to do anything about it.

One staff member stated that on the night of April 9, when Yianni reportedly aspirated on the piece of cake, she had heard him wandering through the house, but she did not direct him back to bed. She also did not see to it that he was wearing the CPAP mask because she knew he would remove it, and therefore, she said, “‘I don’t bother.'”

The report stated that Yianni’s mother became aware that the CPAP machine was not being used based on an internal reporting chip in the machine. As a result, she emailed the Bass River residential director in March, requesting that the group staff make sure to use the machine each night.

The residential director at first told the DDS investigator that she was not aware that Yianni was not using the CPAP machine, but she did not deny that she received his mother’s email and acknowledged that she apparently neglected to follow up on the issue with the group home staff.

The house director acknowledged that she was contacted by an unidentified group home staff member that Yianni was not feeling well and was also told on April 14 by Yianni’s job coach that he appeared to be very ill that day, but she did not follow up with either of these notifications.

The house director also admitted that she falsely told Yianni’s mother on April 13 that Yianni was not ill, but only had allergies. She said that she misled Yianni’s mother about that because she had confused Yianni with another resident.

The report also stated that, according to the staff, the house director, was rarely present in the group home. She told the investigator that she was frequently out at the Bass River office and at meetings, but she was unable to list meetings that would have taken up that much of her time, according to the report.

The report stated that other troubling characteristics of the group home include the fact that none of the staff were scheduled to be awake at night even though Yianni, in particular, was known to wander around at night and to take food from the refrigerator.

In addition, staff who were trained in administering medications, stated that they were only part time and that it was not their responsibility to do so.

Today’s Salem News article noted that Yianni grew up in Rockport and “appeared to thrive and was well-known in the community.” The article stated that a 2005 story in The Gloucester Times described how he had obtained his first job, at Smith’s Hardware, “where he greeted customers with a firm handshake or high-five and sometimes, a hug.” He was later voted king of his high school prom.

As noted, Yianni’s case is not unique. Poor quality care is a serious problem throughout the DDS system, and Yianni’s case is further evidence of that. The Children and Families Committee needs to take the first step in bringing official scrutiny to this system and beginning to suggest needed improvements to it.

State auditor has proposed regs that could weaken the Pacheco Law

The Pacheco Law has over the years been one of the more effective available checks on the runaway privatization of state services.

But the law, which has been the target of continual attacks from privatization proponents, is facing a new challenge, and this time it’s from an unlikely source — the office of State Auditor Suzanne Bump herself.

Bump’s office is charged with overseeing the law, which requires that state agencies seeking to privatize services first make the case to the auditor that doing so will both save the taxpayers’ money and maintain or improve the quality of the services. Given the prominent role her office plays, it isn’t surprising that Bump has been one of the law’s most effective and vocal defenders.

But COFAR is now joining with state employee unions in opposing a number of provisions in a set of regulations, which Bump’s office has recently proposed to govern the continued implementation of the law. Although the Pacheco Law, also known as the Taxpayer Protection Act, has been in effect since 1993, it is only now that the auditor’s office has proposed regulations regarding the law. The comment period on the regulations ends October 31.

We are in agreement with the unions that a number of provisions in the proposed regulations, as they are currently drafted, would appear to make the Pacheco Law less effective in ensuring that when agencies privatize services, they do so for the right reasons.

In recent years, the Pacheco Law has been embroiled in political battles over the privatization of services and functions at the MBTA. The law has also played a more limited, but still contentious, role in the ongoing privatization of human services in Massachusetts.

Last year, Bump’s office approved a proposal under the Pacheco Law to privatize mental health services in southeastern Massachusetts after the for-profit Massachusetts Behavioral Health Partnership (MBHP) claimed it could save $7 million in doing so.

Prior to the auditor’s decision in the MBHP case, we joined the SEIU Local 509 and the AFSCME Council 93 state employee unions in raising concerns about that privatization proposal. We saw some potentially troubling aspects of the proposal that we thought might be realized due to existing loopholes and ambiguities in the Pacheco Law. But we think the solution to that situation should be to strengthen the law, not weaken it.

The first and fourth objections below to the proposed Pacheco Law regulations have been raised by us in written comments sent last week to the state auditor. The second and third objections were raised in preliminary testimony submitted to the auditor last month by SEIU Local 509, and the fifth objection was raised in testimony submitted by AFSCME Council 93:

1. A provision in the proposed regulations would appear to give state agencies an incentive to boost the actual cost of their in-house services if a Pacheco Law review determined that those services should not be privatized.

As part of the review process under the Pacheco law, a state agency seeking to privatize services must demonstrate to the auditor that contracted services would cost less than an In-House Cost Estimate, which is described as “a comprehensive written estimate of the costs of regular agency employees’ providing the subject services in the most efficient and cost-effective manner.”

That requirement lies at the heart of the Pacheco Law because it is meant to ensure that if services are privatized, taxpayers will indeed save money.

The proposed regulations appear at first glance to bolster that cost-saving purpose in stating that if the work is retained in-house after a Pacheco Law review, the state agency is expected make sure the actual work stays within the In-House Cost Estimate.

But the regulations then go on to state that if the agency fails to keep the actual in-house costs down, the agency may issue another request for bids or reopen negotiations with the contractor that would have been the successful bidder under the earlier request for bids.

This provision in the regulations is not in the language of the Pacheco Law itself. And rather than ensuring that costs of in-house services would stay below the In-house Cost Estimate, we think the provision might actually have the opposite effect.

That is because the penalty on the agency for failing to keep the in-house costs down is actually something that the agency would consider to be beneficial to it, i.e. the agency would now be free to privatize the service. It could either issue another request for bids or reopen negotiations with the contractor that lost out to the state employees in the previous review by the auditor.

The regulations do not state that a subsequent review by the auditor would be required under the Pacheco Law if the agency decided to reopen negotiations with the contractor.

In any event, the same state agency that filed under the Pacheco Law to privatize a service would be allowed to keep getting further bites of the privatization apple if it failed to keep in-house costs under control. Thus, this provision would appear to give the agency an incentive to allow in-house costs to rise or even to actively boost those costs in order to do what it wanted in the first place – privatize the service.

Further, there is no provision in the proposed regulations that would require the agency to restore the in-house provision of the service if the service were privatized and the agency was unable to keep the contracted service costs from rising. Thus, our concern is that this provision in the proposed regulations may actually encourage higher costs of both contracted and in-house services rather than serving, as the Pacheco Law intended, to keep those costs low.

2. The proposed regulations appear to weaken provisions in the Pacheco Law that are meant to ensure continuing quality of services.

The Pacheco law, as noted, requires that in addition to demonstrating a cost savings, a state agency seeking to privatize services must demonstrate to the auditor that the quality of the services provided by the private bidder will equal or exceed the quality of services done by state employees.

The proposed regulations state that the agency’s privatization proposal must include a Written Scope of Services that relies on one or more of six performance measures including quality, timeliness, quantity, effectiveness, cost and/or revenue.

Those enumerated performance measures are not in the actual language of the Pacheco Law. But that’s not the problem. The problem lies in the “one or more” statement regarding the performance measures.

As SEIU Local 509 notes, the regulatory provision implies that an agency could choose just one of the performance measures listed in the Written Statement of Services and ignore the rest, and still potentially be certified by the auditor as having satisfied the requirements of the statement.

For instance, a company might provide services that are provided in just as timely a manner as they are provided by state employees, but that does not mean that the private company will provide the services as effectively as state employees or provide the same quantity of services as the state employees provide.

We agree with Local 509 that the regulations should be reworded to require the vendor to demonstrate that it will either equal or exceed all six of the performance measures in the Written Statement of Services.

3. The proposed regulations fail to ensure that contractors will not cut wage rates or health benefits of staff after the contract is renewed.

Under the Pacheco Law review, an outside contractor’s proposed bid to privatize a service must specify a minimum level for wages and health care benefits for its employees.

However, the Pacheco Law does not require a new review by the auditor when a privatization contract expires after five years, and is renewed. As a result, the SEIU and COFAR have raised the concern that a contractor that wins a contract under the Pacheco Law could cut its wage rates and health benefits once the contract was renewed at the end of its minimum five-year term.

According to the SEIU, the Pacheco Law, however, is written in such a way that regulations could be drafted that would require the contractor to maintain existing wage levels and health care benefits when the contract is renewed. The regulations, as drafted, however, do not address that potential outcome.

As the SEIU noted, the language in the regulations related to minimum wages and health insurance benefits of a successful bidder for privatized services avoids stating that these requirements continue on after the expiration of the original privatization contract.

We raised a concern along with the SEIU last year in the mental health service privatization case that the Baker administration was interpreting the Pacheco Law to allow MBHP, the for-profit company, to cut its proposed wage rates within roughly a year after starting to provide those services and potentially to pocket the extra profits. Citing that and other issues, the SEIU ultimately appealed auditor’s approval of the privatization case to the state Supreme Judicial Court, which upheld the auditor’s position.

The SEIU later noted that neither the auditor nor the SJC addressed the concern about potential cuts in wages and benefits under renewed contracts. We believe the regulations should state that a contractor cannot attempt to evade the intent of the Pacheco Law by reducing wages and benefits of employees when the contract expires or is renewed.

4. The proposed regulations require the In-house Cost Estimate to include equipment depreciation, which inappropriately reflects a sunk cost

The proposed regulations state that in determining the in-House Cost Estimate as part of a privatization submission to the auditor, the state agency must consider equipment depreciation, among other things, as a direct cost of in-house services.

The regulations state that depreciation is a calculated cost based on the acquisition cost of equipment or other assets plus transportation and installation costs.

It would seem that requiring depreciation to be included in the In-house Cost Estimate would make it easier for the contractor to beat that cost estimate. At the same time, an acquisition cost is a sunk cost. As such, we do not believe it is relevant in any price comparison going forward.

As Investopedia notes in an article on sunk costs, a sunk cost is:

… a cost that cannot be recovered or changed and is independent of any future costs a business [or public agency] may incur. Since decision-making only affects the future course of business, sunk costs should be irrelevant in the decision-making process. Instead, a decision maker should base her strategy on how to proceed with business or investment activities on future costs.

It seems to us that the acquisition cost of a piece of equipment is a cost that cannot be recovered or changed and is independent of any future costs the agency may incur. More importantly, the depreciation expense associated with an asset cannot be avoided in the future through the privatization of a service.

Say an agency buys a van to transport clients as part of a service that it wants to privatize. Once the van is purchased, it’s a sunk cost even if that cost is depreciated for accounting purposes over the useful life if the vehicle.

As we understand it, the purpose of the Pacheco Law is to compare contractor bids with in-house costs that are considered likely to be avoided in the future if a service is privatized. As the auditor’s Guidelines for Implementing the Commonwealth’s Privatization Law (June 2012) state:

When determining the potential cost savings associated with the contracting out of a service, the appropriate in-house costs to use in the comparison are the avoidable costs (P. 13). (my emphasis)

Even if the agency privatizes the service for which the van is used, the sunk cost incurred in purchasing that van cannot be avoided even if the agency might avoid the cost of directly paying the driver, for instance.

The Pacheco Law itself does not specify which costs must be considered in calculating the in-house cost of providing services other than stating that those costs should include, but not be limited to, pension, insurance, and other employee benefit costs. For that reason, we believe that equipment depreciation costs should not be included in developing the In-House Cost Estimate.

5. The proposed regulations fail to define “permanent employee,” and therefore provide a loophole for circumventing the Pacheco Law

Both the Pacheco Law and the proposed regulations define a “Privatization Contract” that is subject to the law as an agreement “…by which a non-governmental person or entity” provides services that are “substantially similar to” services provided by “regular employees” of the agency.

The problem here is that the law itself doesn’t define the term “regular employee,” and the regulations do not make things much clearer. In fact, the regulations simply state that a “regular employee” is a “permanent employee.” The regulations do not offer any further definition of “permanent employee.”

AFSCME Council 93 notes that the definition of “regular employee” as simply a “permanent employee” creates a potential loophole that could allow agencies to privatize services without a Pacheco Law review.

In fact, it appears that is exactly what happened earlier this year. AFSCME claims the lack in the Pacheco Law of a clear definition of a “regular employee” allowed the state Department of Conservation and Recreation to privatize parking fee collections at state beaches without a Pacheco Law review because the work supposedly involved short-term seasonal workers and not permanent employees.

AFSCME points out, however, that the DCR’s short-term workers are hired on a regular schedule each year in the same way as the department’s long-term seasonal employees who are covered by a collective bargaining contract.

Moreover, even though the contractor chosen by DCR sweetened the privatization deal by offering the department an upfront payment of $1.2 million, AFSCME stated that the privatization deal was still projected by the department to cost taxpayers $500,000 more than keeping the service in-house.

We support AFSCME’s suggestion that at the very least, the regulations should define regular or permanent employees as including any state or public higher education worker covered under a collective bargaining agreement.

In sum, we support the auditor’s efforts to clarify the Pacheco Law as much as possible through the issuance of regulations. We would just urge the auditor to make the changes that we and the unions are suggesting in this case.

Things ‘sliding backwards’ for two men after closure of their sheltered workshops (an update)

Makeshift solutions that were adopted in recent months to help two men cope with the closures last year of their sheltered workshops have not been successful, members of their families say.

“It’s sliding backwards,” Patty Garrity, the sister of Mark Garrity, said in an interview last week. She said a paper shredding experiment that was tried with Mark in March worked only temporarily. Mark soon lost interest in the activity and is bored in his day program, which replaced his sheltered workshop.

In a separate day program, Danny Morin’s temporary work came to an end a few months after it began. In addition, the clients in Danny’s program are now scheduled to be moved into smaller, separate day programs, and Danny’s mother is concerned he could be separated from his long-time girlfriend, another client in his program. The director of the program said that clients’ preferences would be considered in the relocation decisions.

While sheltered workshops were operating for both Mark Garrity and Danny Morin, piecework was always available and both men were satisfied and fulfilled by it, their family members say.

Barbara Govoni, Danny Morin’s mother, is trying to interest state lawmakers in her idea to reintroduce steady piecework activities in day programs for those who desire it. Govoni has proposed legislative language that would require the state to provide a “supportive work environment” to disabled persons who “cannot be comfortably be mainstreamed into a vocational community setting.”

In May, we first reported on the impact of the closures of their sheltered workshops on Mark and Danny and their families.

We noted that paid piecework and assembly work that had been given to Mark and Danny to do in their sheltered workshops were taken away last year and replaced by day program activities that they couldn’t relate to. In each case, their provider agency managed to come up with a makeshift solution to the problem that allowed the men to continue doing work similar to what they had done before.

Now it appears that those makeshift solutions haven’t solved the underlying problems created by the workshop closures for the two men and potentially others.

Sheltered workshops may have closed prematurely in Massachusetts

All sheltered workshop programs were closed in Massachusetts as of last summer as a result of requirements by the federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) that developmentally disabled people work in “integrated employment” settings in which a majority of the workers are not disabled.

But while sheltered workshops have been deemed “segregated” settings because they are offered solely to groups of developmentally disabled persons, many clients and their families and guardians have argued that the programs provide fulfilling, skill-building activities and do not preclude community integration. Moreover, it is not clear that the CMS has necessarily required the shutdown of all sheltered workshops.

In Massachusetts, the Baker administration and former Patrick administration claimed they had no choice but to close all of the workshops in the state, or else the federal government would bring a lawsuit against them. But many other states have apparently not acted in the haste that Massachusetts did in shutting the programs down. Last year, DDS Commissioner Elin Howe, who has since retired, stated that Massachusetts was one of the first states in the country to close all of its workshops.

Paper shredding activity for Mark Garrity didn’t last

At the Road to Responsibility (RTR) day program in Braintree, which Mark Garrity attends, Mark was frustrated for months after his sheltered workshop at the site was closed in September of 2016. Piecework activities that Mark enjoyed doing came to an end and were replaced by nature walks, cooking classes, and a money management class, none of which interested Mark.

After COFAR contacted DDS about Mark’s situation in early March of this year, RTR staff found a paper shredding activity for Mark to do. The activity received verbal approval from the DDS southeast regional director, who determined that it was in compliance with federal regulations.

The paper shredding seemed at first to be a good solution for Mark, and he even got paid for it. But Mark’s sister, Patty Garrity, said that Mark soon sensed a lack of structure and purpose in the activity. Mark is also sometimes asked to use the copy machine and to take the copied documents to staff offices; but Patty says that activity usually occupies only a few minutes of his day.

“I think he’s bored,” Patty said. “Every day I would pick him up and ask how’s it going with the shredding. It didn’t hold his interest.”

Patty said that despite the fact that funding was earmarked to pay Mark for doing the paper shredding, he recently stopped doing it. “Now he’s unproductive, and it’s not fair to him,” she said.

RTR officials have said that they did recently offer Mark an employment opportunity at a company outside of his day program; but Patty did not approve that offer for Mark, contending that Mark is not a suitable candidate for outside or mainstream employment. She said he is not able to produce at a rate that employers require in paying a minimum wage.

While his sheltered workshop was operating, Mark was paid by the piece, so the rate at which he was able to produce was not an issue. Moreover, jobs at the sheltered workshop would rotate. Mark was constantly busy then, Patty said, but now he is chafing under the lack of structure.

In addition, Mark appears to fall outside of at least one work category that still exists at his day program for clients who have been determined to be unable or too high-risk to function in the community outside the program. While those clients have been given work to do each day folding t-shirts, Mark has not been offered that work because he has not been ruled unsuitable for community interaction.

“They’re (the RTR staff) trying to do the best they can,” Patty said, “but the people are bored.”

Work at Work Opportunity Center site is intermittent

At the Work Opportunity Center day program in Agawam which Barbara Govoni’s son, Danny, attends, some piecework has been available intermittently from a company that is located in the same building in the center.

The company, Millennium Press, used to supply piecework activities to the Work Opportunity Center when the Center operated as a sheltered workshop. Now the company rents a portion of the Work Opportunity Center’s building.

The work offered by the Millennium Press to clients of the Work Opportunity Center since the closure of the sheltered workshop complies with federal regulations because non-disabled people also work for that company. Danny Morin and other clients of the Center signed an agreement to be paid a sub-minimum wage for doing the work.

However, Barbara said that the Millennium Press work is not steady. Danny and other clients in the Center were kept busy recently for three to four months putting stickers on envelopes and boxes for the company, but they finished ahead of schedule, she said, and the work came to an end.

Pushing for legislation to bring back workshop activities

Govoni has been trying to interest legislators and her congressman in filing legislation at either the federal or state level that would ensure the legality in Massachusetts and potentially other states of a steady supply of piecework activities for persons who desire them. She met last week with state Representative Brian Ashe, a Democratic legislator who represents her hometown of Hampden, to discuss her proposal.

Such legislation would be similar to language that was inserted in the state budget in Fiscal Years 2015 and 2016 that stated that sheltered workshops would remain open for those who wanted to remain in them. Unfortunately, that language did not prevent the Baker administration from closing all remaining sheltered workshops last year.

Govoni’s proposed legislative language would require the state or states (if her language was enacted by Congress) “to provide a supportive work environment, separate from the mainstream community, to enhance productivity, safety and self-esteem.” The language states that the separate work environment is not meant to exclude “other forms of integration or inclusion.”

We emailed Ashe’s legislative aide last month with our support of Govoni’s proposed legislation, but have not heard back. Govoni said Ashe told her he would bring her idea to the attention of “the proper legislative committee” in the Massachusetts Legislature.

Clients at the Work Opportunity Center will be split into groups

Govoni said the clients in her son’s day program will be split into three groups and that each group will be sent to a different day program location based on where they live. She was told at first that the decisions on the new locations would not be based on any existing preferences the clients had expressed such as preferences for maintaining relationships they may have formed in the Agawam center.

DDS regulations state that the Department must provide services that promote “self‑determination and freedom of choice to the individual’s fullest capability.” If clients are being moved to different locations without regard to their personal preferences, it would appear that they are not being allowed to exercise self-determination or freedom of choice in that respect.

Bob MacDonald, executive director of the Work Opportunity Center, said that after discussing the issue with DDS, he has received clarification that the relocations should take client preferences into account. MacDonald said each relocation decision will take into consideration 1) where the individual lives, 2) the “consumer’s preference,” and 3) the recommendation of the individual’s clinical care (ISP) team.

Without discussing specific people, MacDonald said that if two clients are known to have a relationship or a preference for staying together, that would or should be taken into consideration in the relocation decision.

We hope that Representative Ashe and others in the Legislature will make a sincere effort to promote legislation that will ensure the restoration of steady and meaningful work activities for those in DDS day programs that desire them.

Even if someone believes that DDS-centered work activities tend to segregate or exploit those individuals (and we don’t believe that to be the case), we think everyone should respect the wishes of those individuals and their families and guardians who want to engage in those activities. That is what self-direction and freedom of choice are all about.

Developmentally disabled man nearly dies after group home fails to respond to severe food aspiration symptoms

Yianni Baglaneas, who has Down syndrome, had a great time at a Special Olympics bowling tournament in Peabody on April 9, the day after his 29th birthday.

But later that night in his group home, he apparently aspirated on a piece of birthday cake and nearly died of pneumonia almost a week later because the staff in the residence allegedly did not react to his constant coughing.

“It was like Yianni was drowning while surrounded by people, and no one gave him a hand,” his mother, Anna Eves, said.

Aspirating or inhaling food into the lungs is a particularly serious danger among people with intellectual disabilities, and caretakers are normally trained to take measures to prevent it from happening and to recognize the symptoms when it does happen.

However, the staff of the group home in Peabody run by Bass River, Inc., a Beverly-based provider to the Department of Developmental Services, allegedly failed to take Yianni to a doctor for three days while his coughing continually got worse. In addition, a nurse practitioner at the Cape Ann Medical Center, who finally saw Yianni, apparently misdiagnosed his condition as bronchitis.

Yianni Baglaneas (center) at his Special Olympics bowling tournament on April 9. Hours later, he aspirated on a piece of cake in his group home.

The nurse practitioner prescribed cough and cold medicine for Yianni and sent him back to his group home. She did not do a chest x-ray even though his blood oxygen level was low and his white blood cell count was high, indicating the presence of an infection due to the aspiration.

It was two days after the doctor’s office visit that Anna, who had no idea of the seriousness of her son’s condition, saw him for the first time since the bowling tournament. She was so concerned about how ill he looked that she took him to Addison Gilbert Hospital in Gloucester where he was immediately admitted in critical condition. That was on April 15, six days after he had apparently aspirated on the piece of cake.

No one from the group home had informed Anna or her husband of Yianni’s worsening condition during that week. The house director had only emailed Anna at one point that Yianni was being taken to the doctor with a cough and a runny nose, and later told her the doctor said her son was suffering from allergies.

“I will never forget the ICU doctor telling me he was in critical condition and asking me if I wanted him to do everything he could to save his life,” Anna said. A nurse told her that her son had been hours away from dying when he was admitted to the hospital.

COFAR emailed Larry Lusignan, executive director of Bass River, Inc., to ask whether he would comment on the case and whether his agency was taking steps to better train staff in how to recognize and react to symptoms of aspiration pneumonia and other illnesses among group home clients.

Lusignan declined to comment, stating in a reply email that “…issues of confidentiality prevent me from disclosing information of any kind regarding our service delivery to individuals, or even the identification of any individuals served.”

Anna said the episode has made her “distraught about the level of abuse and negligence that happens in group homes in Massachusetts.” She said she has begun looking for other parents “to join with to shine a spotlight on this and change things so that these things stop happening.”

COFAR has long sought a state investigation of group home conditions in Massachusetts – particularly in privatized group homes. Abuse and neglect in the DDS system is a topic that now and then appears on the political agenda, but rarely attracts sustained legislative attention.

In 2013, after The New York Times and The Hartford Courant both ran separate series on abuse and neglect in privatized group homes in their respective states, Senator Chris Murphy of Connecticut called for a federal investigation of deaths and injuries in privatized care. But Murphy later appeared to back off his call for a comprehensive federal review.

“The bottom fell out”

Anna Eves described her son as a “sweetheart of a guy” and a beloved figure in his hometown of Rockport. He was so popular in high school that he was named the school’s prom king, and he attended graduation and received a standing ovation there even though he didn’t receive a diploma.

But the “bottom fell out” of his care after he turned 22, his mother says. That was when his eligibility for special education funding ended and he became eligible for DDS services.

For several years after turning 22, Yianni lived at home with his parents. But even though he is nonverbal, he wanted independence and was lonely after most of his siblings moved away to start their lives, his mother said. He was excited when in June 2016, he moved into the DDS-funded group home operated by Bass River.

But after what happened in April, less than a year into his residence in the group home, his parents have taken him back home.

A timeline of inattention

Anna had to piece together what had happened to her son in April by talking to caregivers, doctors, and others. She filed a complaint with the Disabled Persons Protection Commission (DPPC) on April 17, and was still waiting as of today (August 23) for the results of the investigation of the matter. That investigation was actually referred by the DPPC to DDS.

Based on Anna’s account, we have pieced together the following timeline of events involving her son before and after he developed symptoms of apparent aspiration:

Saturday, April 8: Yianni’s 29th birthday. He spent most of the day with his parents.

Sunday, April 9: Yanni’s parents took him to a Special Olympics bowling tournament in Peabody. He showed no sign of illness.

Back in his group home later that night, Yianni is believed to have aspirated on a piece of birthday cake, which he had gotten out of bed to eat. His roommate, who had made the cake, was concerned about him.

Anna said her son has had a history of putting too much food in his mouth and not chewing it sufficiently before swallowing. She said the group home staff was aware of that. Yet, to his mother’s knowledge, no one in the group home was aware that he had gotten the cake out of the refrigerator that night.

Monday and Tuesday, April 10 and 11: Yianni was continually coughing in his group home. His roommate, who is verbal, was worried enough that he told his mother he thought Yianni was very sick and that it had been caused by the cake he had made. But no one from the group home apparently made that connection, took any action, or called Yianni’s parents.

Wednesday, April 12: Yianni was sent as usual to his day habilitation program in Beverly, run by EMARC, a DDS provider. He was coughing so much that the day program nurse sat with him at lunch because she was afraid he was going to choke on his food. The nurse reportedly later suggested to the Bass River group home staff that Yianni be taken to a doctor, but the nurse did not arrange for that herself.

Anna said the nurse later changed her story and told her Yianni had been coughing only moderately at his day program.

Thursday, April 13: Anna received an email that morning from the group home director, stating that Yianni had woken up that morning not feeling well and that he was being taken to see a nurse practitioner at his doctor’s office that afternoon.

The email from the house director said that Yianni had congestion, a cough and “a bit of a runny nose,” so Anna was not overly concerned. The email did not indicate that Yianni’s coughing had been going on for days or that it was getting worse. It was the first time anyone in the group home had sent any message to Anna that week indicating that her son was not well.

The house director added that the medical appointment was at 1:30 p.m. and that she would update Anna with the results. A staff member did finally take Yianni to his primary care doctor’s office at the Cape Ann Medical Center in Gloucester.

Anna said she learned that the group home staff member told the nurse practitioner falsely that Yianni had started coughing only that day. The nurse practitioner took a blood sample, but did not do a chest x-ray.

According to Anna, the blood test showed a high white blood cell count consistent with an infection, and a potentially low blood oxygen level of 90. She said the blood oxygen level should be 99 or 100.

The nurse practitioner diagnosed Yianni’s condition as bronchitis and an upper-respiratory infection. She performed a nebulizer treatment on him and prescribed cough syrup and Mucinex and Robitussin, which are over-the-counter decongestants. Despite the results of the blood test and the low blood oxygen count, the nurse determined that Yianni could return to his residence.

Anna said she later learned that the group home staff had removed her name and phone number as her son’s primary medical contact and substituted the group home phone number without her permission even though she is her son’s legal guardian. As a result, no one at the medical center had any means of contacting her regarding her son.

That same afternoon, Anna said, the house director called her, but it was actually by accident. The director had meant to call Yianni’s roommate’s mother. But Anna pressed her during the phone call about her son’s doctor’s visit. The house director appeared to be rushed, she said, and told her only that her son had allergies.

Friday, April 14: The group home director took Yianni as usual to meet with his job training coach at Community Enterprises, Inc., a DDS provider, in Salem. The job coach later told Anna she was alarmed at how sick Yianni appeared. However, the job coach did not take any action or contact anyone about him at the time.

Saturday, April 15: A group home staff member dropped Yianni off at a Special Olympics track practice in Gloucester. His parents were there to meet him, and it was the first time they had seen him since Sunday, April 9, the day after his birthday.

Anna said that when she first saw the group home staff member at the Special Olympics event, her son was in the bathroom. “She (the staff member) didn’t say anything,” Anna said. “She just handed my husband, James, his overnight bag and drove away.” When her son emerged from the bathroom, Anna said, she and her husband were shocked at how ill he appeared. “He was coughing and his eyes were sunken,” she said. A Special Olympics coach approached her and said her son did not appear well enough to participate in the practice.

Anna took her son home and tried to give him lunch, but he wouldn’t eat. Then she looked into his overnight bag and saw the Mucinex for congestion. “I thought he just had allergies, but when I saw the Mucinex, I thought right away something was not right.” At that point, Yianni appeared lethargic and didn’t want to move.

Anna thought about calling an ambulance, but then drove him to the emergency room at Addison Gilbert Hospital in Gloucester. There, his blood oxygen was measured at 50, which is not compatible with long-term survival. His right lung was completely filled with fluid. He was admitted directly to the ICU in critical condition.

Monday, April 17: Yianni was placed on a ventilator on which he would remain for 11 days. Anna called the group home in the morning and left a voice message that Yianni was in the hospital ICU in critical condition on a ventilator with severe pneumonia.

Yianni in the ICU at Addison Gilbert Hospital in Gloucester

Tuesday, April 18: The group home director returned Anna’s call from the previous day. “She said she heard Yianni was sick and was sorry to hear it,” Anna said.

Anna said she asked the house director why she had not informed her during the previous week that her son was sick and why she had told her falsely that he only had allergies. She said the director responded by saying she didn’t know why she had not told her the truth about the situation. She said the director then said to her, “’It’s all my fault.’”

Thursday April 20: Larry Lusignan, executive director of Bass River, Inc. called Anna “to ask what happened,” she said. She said she told him her son would not be returning to the group home and that she had made arrangements to pick up his belongings from the residence. She said Lusignan never acknowledged any wrongdoing.

Sunday, April 23: Yianni was moved from Addison Gilbert to the ICU at Mass General Hospital.

Sunday, April 30: Yianni was moved out of the ICU at Mass General and into the hospital’s Respiratory Acute Care Unit.

Anna said that Yianni spent about a week in the Respiratory Care Unit at Mass General and then spent about three weeks at Spaulding Rehabilitation Hospital.

Thursday, May 25: Yianni was released from Spaulding Rehab and went home to his parents’ house in Rockport.

The ordeal is not over for Yianni. Anna said she was told it could take six months to a year for him to fully recover. His parents are not sure, in fact, that he will ever completely recover. Since his hospitalization, he has continued to need an inhaler and gets out of breath from walking. He needs to sleep at night with supplemental oxygen.

Anna is not sure what is next for her son or what type of residential care would be appropriate for him. “He’ll be home with us until I am 100 percent confident in any placement,” she said.

We think Yianni might be a good candidate for a state-operated group home in which the staff is more highly trained than is largely the case in privatized residences. As we have noted, however, the administration appears to be phasing out state-operated residential options for people.

We hope this case will demonstrate the continuing need for state-run residential programs and that it will lead to better training of staff in all DDS residential facilities. Unfortunately, however, incidents like this seem to continue to happen with regularity in the DDS system.

We would also hope this case will finally spark a hearing by the Legislature’s Children, Families, and Persons with Disabilities Committee into issues surrounding oversight of privatized human services.

The August issue of The COFAR Voice is now online

The August issue of our long-running newsletter, The COFAR Voice, is now online. You can find it here.

The latest issue is chock full as usual of the kind of insightful and informative reporting on issues relating to developmental disabilities that you will find nowhere else.

Articles in the issue include:

- Payments to professional guardians by DDS are characterized by a lack of transparency and accountability: A COFAR investigation

- The number of residents in state-operated group homes appears to be dropping in Massachusetts as funding for those critically important facilities continues to be cut.

- A developmentally disabled woman continues to be kept in isolation by DDS, and the media won’t report it.

- Nearly a year after the last sheltered workshops were closed in Massachusetts, two families are struggling with a new system that is confusing and is providing their loved ones with less meaningful activities.

- A Harvard researcher is helping to lead a major, multi-center study of the links between Down syndrome and Alzheimer’s disease.

- John Sullivan and Roland Charpentier, two tireless advocates for the developmentally disabled, have left us.

You can also find a link to the August newsletter on our website at www.cofar.org.

Living wage in Massachusetts suffers a setback

In an apparently little-noticed setback to the effort to raise the minimum wage in Massachusetts, the legislative conference committee on the state budget rejected a living wage for direct-care workers in human services earlier this month.

The conference committee tossed out language that would have required corporate human services providers to boost the pay of their direct-care workers to $15 per hour.

That language had been proposed by Senator Jamie Eldridge and had been adopted in the Senate budget, but it wasn’t in the House budget, so it went to the conference committee. The conference committee chose not to include Eldridge’s language in its final budget even though the inclusion of the language would not have affected the budget’s bottom line.

In a press release issued in May when the Senate adopted his measure, Eldridge termed a $15-per-hour wage for direct-care workers “part of a growing movement to provide a living wage to every worker in Massachusetts.”

An aide to Eldridge said last week that the direct-care wage boost had been requested by SEIU Local 509, the state-employee union that represents human services workers. The aide said, however, that Eldridge had no immediate plans to file legislation to keep the momentum going for that living wage.

We have urged Senator Eldridge to keep the living wage movement going. In the human services arena, the lack of a living wage for direct-care workers appears to be closely related to the rapidly increasing privatization of care.

As state funding has been boosted to corporate providers serving the Department of Developmental Services and other human services departments, a large bureaucracy of executive-level personnel has arisen in those provider agencies. That executive bureaucracy is suppressing wages of front-line, direct-care workers and is at least partly responsible for the rapidly rising cost of the human services budget.

Ironically, a key reason for a continuing effort by the administration and Legislature to privatize human services has been to save money. However, we think that privatization is actually having the opposite effect.

In May, the SEIU released a report charging that major increases in state funding to corporate human services providers during the past six years had boosted the providers’ CEO pay to an average of $239,500, but that direct-care workers were not getting a proportionate share of that additional funding. As of Fiscal 2016, direct-care workers employed by the providers were paid an average of only $13.60 an hour.

Eldridge’s budget language stated that providers must spend up to 75 percent of their state funding each year in order to raise the wages of their direct-care workers to $15 per hour.

While the conference committee enacted deep cuts in DDS and other state-run programs as a result of a growing projected budget deficit, the Senate language on direct-care pay would have only required that providers direct more of the funding they were already getting from the state to their direct-care workers.

The SEIU’s report on the compensation disparity confirmed our own concerns in that regard. A survey we did in 2015 found that more than 600 executives employed by corporate human service providers in Massachusetts received some $100 million per year in salaries and other compensation.

Along those lines, we are concerned that the ongoing privatization of human services is having a devastating impact on state-run programs, particularly within DDS. As we recently reported, funding for critically important state-run programs, such as state-operated group homes and service coordinators, is being systematically cut while funding is rapidly boosted to corporate providers.

This additional disparity in human services funding is resulting in the elimination of choices to individuals and families in the system and perpetuating a race to the bottom in care.

There appear to be few if any people in the Legislature who are questioning the runaway privatization of human services much less who are willing to buck the trend. An effort to require providers to offer a living wage to their direct-care workers would be a start in that direction.

We hope Senator Eldridge will continue to push for the direct-care living wage, and that he and others will begin to examine the connections that exist between low wages for direct-care workers and the ongoing, unchecked privatization of human services.

DDS not commenting on future of state-operated group homes as FY ’18 funding is sharply cut

In the wake of a projected state budget deficit, Governor Baker and the Legislature have approved their deepest cuts yet in funding for state-operated group homes and other programs managed by the Department of Developmental Services.

Yet funding for privatized group homes will still increase by tens of millions of dollars under Baker’s final Fiscal Year 2018 budget, although that increase will be somewhat less than what Baker had originally proposed.

The cuts in Baker’s final budget for Fiscal 2018, which began July 1, include a $10.5 million reduction in funding for the state-operated group homes and a $2.2 million reduction in the DDS administrative account, which funds critically important service coordinators. The state-operated group homes are the hardest hit of any DDS funding account.

We have previously reported that the administration and Legislature appeared to have placed a priority on funding privatized DDS services. The final Fiscal 2018 budget may provide the sharpest indication yet of that priority, which is reflected in the chart below. The chart shows final appropriations since Fiscal 2012 for key DDS privatized and state-run program line items.

In January, when Baker submitted his Fiscal 2018 budget to the Legislature, he proposed $59.9 million in additional funding for privatized DDS group homes, while at the same time proposing a $1.8 million cut in the state-operated group home account.

The House and Senate initially largely rubber-stamped Baker’s DDS budget plans. Then, in early July, a House-Senate conference committee, working behind closed doors, recommended a cut more than five times deeper for the state-operated group homes — $10.4 million.

The governor’s final budget went even further, cutting state-operated group home funding by $10.5 million for Fiscal 2018. That amounts to a $15.6 million cut when adjusted for inflation.

Meanwhile, the governor’s final budget only moderately reduced the increase Baker had initially proposed for the privatized group home system — lowering that proposed $59.9 million increase to $47.6 million.

Similarly, the governor had initially proposed a cut of $97,000 in the DDS administrative line item, which funds the service coordinators. However, while the House and Senate initially rubber-stamped that cut, the conference committee in July deepened the cut to more than $2.1 million. The governor then further cut the administrative line item in his final budget by an additional $50,000, deepening the total cut to nearly $2.2 million.

Service coordinators are DDS employees who help ensure that clients throughout the DDS system receive the services to which they are entitled under their care plans. As COFAR has reported, service coordinators could find their jobs threatened by privatized “service brokers.”

Also slated for deepened cuts are the state-run Wrentham and Hogan developmental centers — the two remaining facilities in Massachusetts that are required to meet stringent federal Intermediate Care Facility (ICF) standards.

In January, Baker proposed a $2.4 million cut in the developmental centers line item. The conference committee more than doubled the size of that cut, to $5.4 million, and the governor’s final budget adopted the conference committee’s number.

DDS not commenting on fate of state-operated group homes

Despite the fact that the state-run group homes have been targeted for the deepest cuts in the DDS budget, DDS is apparently not commenting on whether it has any plans to phase out the state-operated group homes entirely.

After reporting in March that there had been a drop in the number of people living in state-operated group homes, we asked then outgoing DDS Commissioner Elin Howe whether DDS had any policies or plans for the phase-down or closure of those facilities in Massachusetts. We never received a response to our email query. Howe retired from her position on July 14.

In March, an assistant general counsel at DDS said that the Department had no public records pertaining to any policies or plans to close the state-operated group homes.

Even if there are no written policies regarding the phase-down of state-operated group homes, the evidence seems to be mounting that state-run DDS services are under siege in Massachusetts.

We will continue to monitor the funding levels proposed and approved for state-run DDS programs. So far, the trends do not look good. Please call your state legislators and express your concern. You can find your legislators at: https://malegislature.gov/Search/FindMyLegislator

State’s system of paying guardians and attorneys for the developmentally disabled appears secretive and poorly overseen

State payments to attorneys and corporate providers to serve as guardians of developmentally disabled clients are rising rapidly, yet the payment system appears to be secretive and subject to spotty oversight.

An investigation by COFAR shows the system in Massachusetts and regulations that support it also appear to give professional guardians an incentive to do little work representing individual clients while taking on as many clients as possible.

In addition, the fact that professional guardians are paid by the Department of Developmental Services appears to interfere with their legal obligation to act in the best interest of their disabled clients. We have found in a number of cases that both professional guardians and attorneys appointed to provide legal representation to disabled clients have sided with DDS when family members have gotten into disputes with DDS over the care of those clients.

In one case on which we have reported, a developmentally disabled woman’s state-appointed attorney has sided with a DDS-paid guardian in not allowing any family visitation of the woman for an indefinite period of time. In that case, David Barr, the father of the woman, and Ashley Barr, the woman’s sister, have been banned from all contact with her, and even from knowing her whereabouts, for more than a year and a half.

We believe this and similar cases raise questions whether DDS-paid guardians and state-paid attorneys consistently act in the best interests of their clients.

COFAR examined probate court documents and payment data involving attorneys and corporate entities paid by DDS to provide guardianship services to persons in which family members are not available or have been removed as guardians.

COFAR has also sought information on the payment of attorneys who are hired under the probate system to provide legal representation to incapacitated persons. In those cases, the court approves attorneys as counsel, and the attorneys are paid by a state agency called the Committee for Public Counsel Services (CPCS). As noted below, the CPCS did not respond to COFAR’s request for that information.

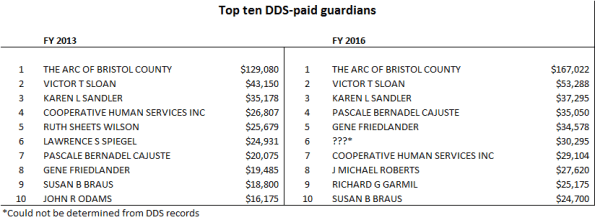

The following chart shows the top-paid DDS guardians in Fiscal Years 2013 and 2016:

COFAR considers becoming a guardian to be a critically important step for family members when loved ones with intellectual and incapacitating developmental disabilities reach the age of 18. After an individual reaches that age, only that person or a guardian acting on their behalf has legal standing to make decisions about their care in the DDS system.

Anyone wishing to become a guardian of a developmentally disabled or otherwise incapacitated person must apply to the probate court to do so. When DDS wishes to pay an attorney to serve as a professional guardian of an individual, it recommends to the court that the attorney be appointed as the guardian.

Under probate law, there are no specific qualifications required of professional guardians such as expertise in mental health issues.

Information about professional guardians and attorneys difficult to obtain

Information about what professional guardians and attorneys do for the clients they are paid to represent in the probate system can be difficult or prohibitively expensive to obtain from DDS and particularly from the CPCS.

Because the CPCS is technically a part of the judicial branch of government, it is not subject to the state Public Records law, according to an attorney we consulted with the state’s Public Records Division. The CPCS would not provide COFAR with any information about the attorneys they employ or the amounts paid to them.

DDS did provide us with a list of guardians it employs and payments made to them, in response to a Public Records request (see chart above showing the top 10 highest paid guardians in Fiscal 2013 and 2016). However, the Department said it would have to pull records from “multiple offices” in order to determine what those guardians do for their payments and how many clients they represent. That information would cost us $3,000, a department attorney wrote.

The DDS payment data also raised a number of questions that the Department did not answer. For instance, there was no guardian listed as the recipient of payments totaling $30,295 on the DDS list in Fiscal 2016. DDS stated that it had no records indicating who those payments may have gone to. (See payment chart above with “???” notation.)

DDS’s response indicates that the department does not have a centralized accounting system to keep track of invoices submitted by guardians for payment. (It appears that this money comes from the clients’ individual Medicaid accounts, but is paid through DDS.)

Independent guardianship office proposed to address accountability issues

In one apparent effort to address at least some of the accountability issues with the current system, a bill in the Legislature (H. 3027) would establish an independent agency called a “Public Guardian,” which would have centralized authority over the hiring and payment of guardians in cases in which family members are not available to serve as guardians of incapacitated people. Under the bill, the Public Guardian would take over the responsibility from agencies such as DDS of recommending and paying guardians.

While COFAR supports the concept of an independent public guardian, we are concerned that H. 3027 specifies that the public guardian would not actually be a public agency, but rather would be a nonprofit agency. We believe the public guardian should be a public agency, which would be subject to the state Public Records Law and other legal requirements that apply to public agencies.

COFAR also strongly supports a second reform measure (H. 887), which would boost the rights of families in the DDS/probate system. The bill would require probate court judges to presume that the parents of incapacitated persons are the suitable guardians for those persons. The measure, however, has never gotten out of the Judiciary Committee.

Payments to guardians on the rise

The list provided by DDS of guardians it employs shows that the department’s total payments to guardians increased between Fiscal 2013 and 2016 from $602,474 to $800,476 – a 33% hike. The number of paid guardians rose from 68 to 80.

The highest-paid guardian was actually a corporate provider – The Arc of Bristol Country — whose total payments rose from $129,000 to $167,000 from Fiscal 2013 to 2016, a 29% increase. The payments to the Arc constituted more than 20%, or one fifth, of the total payments to all guardians in Fiscal 2016.

The second highest-paid guardian in both years was Victor Sloan, an attorney in Uxbridge. His payments from DDS rose from $43,150 in Fiscal 2013 to $53,288 in Fiscal 2016. Sloan’s website lists him a practicing attorney who does criminal defense cases and estate planning in addition to guardianships.

In email messages to Sloan and Michael Andrade, the CEO of the Arc of Bristol County, COFAR asked how many developmentally disabled clients they represented as guardians and how often they were able to visit those clients. In the case of the Arc, we asked how large their staff of guardians was and whether there was a maximum number of persons for whom each member of their staff was allowed to provide services.

Neither Sloan nor Andrade responded to our email or to a follow-up message left with each of them.

The DDS records show that payments to some guardians actually dropped between Fiscal 2013 and 2016, implying that they had lost wards. However, other guardians saw large increases in their payments, which sometimes doubled or even tripled or more in that period. For instance, payments to a Patrick Murray rose from $3,025 to $15,860 from 2013 to 2016 – a 424% increase.

In the Barr case (noted above), payments to the guardian, Dorothy Wallace, rose from $13,000 in Fiscal 2013 to $20,100 in Fiscal 2016 — a 55% increase.

The system appears to reward professional guardians with multiple clients

State regulations governing payments to guardians cap payments per client at $50 per hour, and cap the number of hours that guardians can spend serving individual clients at 24 hours per client per year [130 CMR 520.026 (E)(3)(d)]. Yet, the regulations do not appear to limit the number of clients an individual guardian can represent.

While the regulatory caps would appear to be intended to limit the amount of funding that professional guardians can receive per client, they also appear to provide an incentive to guardians to increase the number of clients they provide services to.

Based on those regulatory caps, we have calculated that Sloan was paid for providing guardianship services to at least 44 clients in Fiscal 2016. The Arc of Bristol County would have had at least 139 clients in that year. When guardians represent large numbers of clients, the ability of those guardians to act in their clients’ interest would appear to decline.

Moreover, the guardianships for which DDS has paid Sloan appear to be only a portion of the probate-court-related work that Sloan does.

Court records show that Sloan has been involved as a guardian, guardian ad litem, attorney, or as a “Rogers Monitor” for incapacitated persons in 118 cases in four separate counties between a seven-year period from Fiscal 2009 to 2015. That includes 14 persons for whom he was appointed as a Rogers Monitor, 75 persons for whom he was appointed as an attorney, 19 cases in which he was appointed as a guardian ad litem, and six cases in which he was appointed as a guardian.

Those six cases in which Sloan was appointed as a guardian appear to be in addition to our estimated 44 cases in which Sloan has been paid by DDS to be a guardian.

An annual client care plan filed in Worcester Probate and Family Court by Sloan does appear to raise questions about the amount of time Sloan spent representing a DDS client from May 2016 to May 2017.

Sloan described the client in the care plan as mildly developmentally disabled and as residing in a group home. Asked on the form to describe the “nature and frequency” of his visits with the client and his caregivers, Sloan stated only that he visited the client and his care givers “at least regularly, and have regular phone and email contact with his residential and day program staff.”

However, stating that he had visited his client “at least regularly” does not either specify the frequency of the visits nor describe their nature.

Sloan’s care plan report contained no critical remarks about the client’s care. He stated that the man’s needs “are being met in his current residential placement,” and that he was attending “an appropriate day program.”

DDS appears to have no centralized accounting system for paid guardians

In a May 10 Public Records law request, we asked DDS for information on the number of clients each paid guardian in its system had and the number of hours the guardians spent with their clients. In a response later that month, a DDS assistant general counsel stated that providing information on the number of clients and hours spent by guardians would require DDS to collect invoices from “multiple DDS offices,” which would take at least 30 hours of “search and collection time” for each of four regional offices. At a cost of $25 per hour, that would cost us at least $3,000, the assistant general counsel’s letter said.

In a subsequent letter sent to us in June, the assistant general counsel stated that it would take an estimated 14 hours of staff time to identify the invoices submitted in Fiscal 2016 from just one guardianship entity — the Arc of Bristol County.

The apparent difficulty that DDS has in locating invoices for payment from guardians in its system raises questions about the adequacy of its internal financial controls, in our view. The DDS central office does not even keep a record of the number of clients each of its guardians represents, according to the assistant general counsel’s May letter.

PriceWaterhouseCoopers notes the importance of centralized, or at least standardized internal controls in large nonprofit institutions such as colleges and universities. We believe a large public agency such as DDS should also have a centralized internal control system, and DDS may lack that with regard to the guardians it employs.

No response from the CPCS

On May 10, we also filed a request with the Committee for Public Counsel Services (CPCS) for a list of attorneys who are selected for appointment to represent clients of the DDS who are subject to guardianship, from Fiscal Year 2013 to the present.

As part of our information request, we asked for a list of the total annual payments made the attorneys from Fiscal 2013 to the present, and the total hours spent each year by those attorneys representing and visiting their clients.

We did not receive a response from the CPCS to our information request. We contacted the state Supervisor of Public Records with regard to the matter and were told that the CPCS is considered to be a part of the judicial branch of state government, which is not subject to the Public Records law.

DDS/Probate system needs reform

As noted, we see a potential conflict of interest in allowing DDS to recommend and pay guardians to represent people in the agency’s care. Along those lines, we are concerned that DDS has in a number of cases recommended attorneys, corporate providers, and other unrelated parties as guardians of individuals over the objections of family members of the individuals.

Also, in light of the increasing amounts paid to guardians by DDS, we are concerned that there is a potential for inadequate representation when paid guardians have large numbers of clients. Yet the payment system for guardians, in particular, appears to encourage those professional guardians to take on more and more clients.

We are also concerned that the system encourages DDS-paid guardians and CPCS attorneys to side together against the interests and wishes of families and individuals caught up in that system.

We think reform of the DDS/probate system is sorely needed, particularly with regard to payment of guardians and other financial practices. Those reforms should make the system more responsive to families, more transparent, and more accountable.

A public guardian may be the answer to many of these issues and problems, but, as noted, we think the public guardian should be just that — public. In the meantime, we urge the Judiciary Committee to finally vote to approve H. 887, which would boost the rights of families in the system by requiring probate judges to presume parents to be suitable guardians.

We will look further into these issues as we advocate for reform of the DDS/probate system.

Isolation of developmentally disabled woman continues after more than a year and a half

It has been a year and seven months since David Barr and his daughter, Ashley, were last informed by the Department of Developmental Services of the whereabouts of David’s other daughter, a young woman with a developmental disability and mental illness.

The 29-year-old woman, whose name is being withheld for privacy reasons, is being kept in an undisclosed residence. All contact with her by her father and sister was cut off for unclear reasons by a DDS-paid guardian in November of 2015.

Although Dorothy Wallace, the DDS guardian, said in August 2015 that her goal was to allow the woman to have family contact, it still hasn’t happened for reasons that have never been revealed to David or Ashley. For unknown reasons, the only family member who has been allowed to visit the woman is an aunt who has apparently agreed not to reveal the woman’s location to the woman’s father or sister.

In an email last week, Ashley Barr told COFAR that her father has personally filed in the Essex County Probate and Family Court to intervene in the case and to seek permission to visit his daughter. But to date, he has not heard from the court.

The probate court has not issued any orders barring visitation with the woman. The denial of virtually all family contact appears to be a decision of the woman’s guardian and possibly DDS.

The Barrs have been unable to afford the cost of hiring a lawyer to pursue their case in probate court. As we have reported in another case, it is extremely difficult to prevail in any probate court proceeding in Massachusetts if you are not a legal guardian or appear without a lawyer.

David and Ashley have contacted their local state legislators, but have gotten little or no help from them. COFAR has attempted to intervene with mainstream media outlets and the legislators in support of visitation for David and Ashley, also to no avail.

David and Ashley Barr