State’s system of paying guardians and attorneys for the developmentally disabled appears secretive and poorly overseen

State payments to attorneys and corporate providers to serve as guardians of developmentally disabled clients are rising rapidly, yet the payment system appears to be secretive and subject to spotty oversight.

An investigation by COFAR shows the system in Massachusetts and regulations that support it also appear to give professional guardians an incentive to do little work representing individual clients while taking on as many clients as possible.

In addition, the fact that professional guardians are paid by the Department of Developmental Services appears to interfere with their legal obligation to act in the best interest of their disabled clients. We have found in a number of cases that both professional guardians and attorneys appointed to provide legal representation to disabled clients have sided with DDS when family members have gotten into disputes with DDS over the care of those clients.

In one case on which we have reported, a developmentally disabled woman’s state-appointed attorney has sided with a DDS-paid guardian in not allowing any family visitation of the woman for an indefinite period of time. In that case, David Barr, the father of the woman, and Ashley Barr, the woman’s sister, have been banned from all contact with her, and even from knowing her whereabouts, for more than a year and a half.

We believe this and similar cases raise questions whether DDS-paid guardians and state-paid attorneys consistently act in the best interests of their clients.

COFAR examined probate court documents and payment data involving attorneys and corporate entities paid by DDS to provide guardianship services to persons in which family members are not available or have been removed as guardians.

COFAR has also sought information on the payment of attorneys who are hired under the probate system to provide legal representation to incapacitated persons. In those cases, the court approves attorneys as counsel, and the attorneys are paid by a state agency called the Committee for Public Counsel Services (CPCS). As noted below, the CPCS did not respond to COFAR’s request for that information.

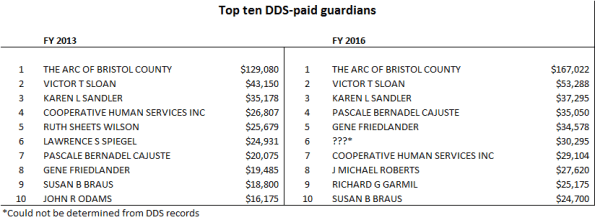

The following chart shows the top-paid DDS guardians in Fiscal Years 2013 and 2016:

COFAR considers becoming a guardian to be a critically important step for family members when loved ones with intellectual and incapacitating developmental disabilities reach the age of 18. After an individual reaches that age, only that person or a guardian acting on their behalf has legal standing to make decisions about their care in the DDS system.

Anyone wishing to become a guardian of a developmentally disabled or otherwise incapacitated person must apply to the probate court to do so. When DDS wishes to pay an attorney to serve as a professional guardian of an individual, it recommends to the court that the attorney be appointed as the guardian.

Under probate law, there are no specific qualifications required of professional guardians such as expertise in mental health issues.

Information about professional guardians and attorneys difficult to obtain

Information about what professional guardians and attorneys do for the clients they are paid to represent in the probate system can be difficult or prohibitively expensive to obtain from DDS and particularly from the CPCS.

Because the CPCS is technically a part of the judicial branch of government, it is not subject to the state Public Records law, according to an attorney we consulted with the state’s Public Records Division. The CPCS would not provide COFAR with any information about the attorneys they employ or the amounts paid to them.

DDS did provide us with a list of guardians it employs and payments made to them, in response to a Public Records request (see chart above showing the top 10 highest paid guardians in Fiscal 2013 and 2016). However, the Department said it would have to pull records from “multiple offices” in order to determine what those guardians do for their payments and how many clients they represent. That information would cost us $3,000, a department attorney wrote.

The DDS payment data also raised a number of questions that the Department did not answer. For instance, there was no guardian listed as the recipient of payments totaling $30,295 on the DDS list in Fiscal 2016. DDS stated that it had no records indicating who those payments may have gone to. (See payment chart above with “???” notation.)

DDS’s response indicates that the department does not have a centralized accounting system to keep track of invoices submitted by guardians for payment. (It appears that this money comes from the clients’ individual Medicaid accounts, but is paid through DDS.)

Independent guardianship office proposed to address accountability issues

In one apparent effort to address at least some of the accountability issues with the current system, a bill in the Legislature (H. 3027) would establish an independent agency called a “Public Guardian,” which would have centralized authority over the hiring and payment of guardians in cases in which family members are not available to serve as guardians of incapacitated people. Under the bill, the Public Guardian would take over the responsibility from agencies such as DDS of recommending and paying guardians.

While COFAR supports the concept of an independent public guardian, we are concerned that H. 3027 specifies that the public guardian would not actually be a public agency, but rather would be a nonprofit agency. We believe the public guardian should be a public agency, which would be subject to the state Public Records Law and other legal requirements that apply to public agencies.

COFAR also strongly supports a second reform measure (H. 887), which would boost the rights of families in the DDS/probate system. The bill would require probate court judges to presume that the parents of incapacitated persons are the suitable guardians for those persons. The measure, however, has never gotten out of the Judiciary Committee.

Payments to guardians on the rise

The list provided by DDS of guardians it employs shows that the department’s total payments to guardians increased between Fiscal 2013 and 2016 from $602,474 to $800,476 – a 33% hike. The number of paid guardians rose from 68 to 80.

The highest-paid guardian was actually a corporate provider – The Arc of Bristol Country — whose total payments rose from $129,000 to $167,000 from Fiscal 2013 to 2016, a 29% increase. The payments to the Arc constituted more than 20%, or one fifth, of the total payments to all guardians in Fiscal 2016.

The second highest-paid guardian in both years was Victor Sloan, an attorney in Uxbridge. His payments from DDS rose from $43,150 in Fiscal 2013 to $53,288 in Fiscal 2016. Sloan’s website lists him a practicing attorney who does criminal defense cases and estate planning in addition to guardianships.

In email messages to Sloan and Michael Andrade, the CEO of the Arc of Bristol County, COFAR asked how many developmentally disabled clients they represented as guardians and how often they were able to visit those clients. In the case of the Arc, we asked how large their staff of guardians was and whether there was a maximum number of persons for whom each member of their staff was allowed to provide services.

Neither Sloan nor Andrade responded to our email or to a follow-up message left with each of them.

The DDS records show that payments to some guardians actually dropped between Fiscal 2013 and 2016, implying that they had lost wards. However, other guardians saw large increases in their payments, which sometimes doubled or even tripled or more in that period. For instance, payments to a Patrick Murray rose from $3,025 to $15,860 from 2013 to 2016 – a 424% increase.

In the Barr case (noted above), payments to the guardian, Dorothy Wallace, rose from $13,000 in Fiscal 2013 to $20,100 in Fiscal 2016 — a 55% increase.

The system appears to reward professional guardians with multiple clients

State regulations governing payments to guardians cap payments per client at $50 per hour, and cap the number of hours that guardians can spend serving individual clients at 24 hours per client per year [130 CMR 520.026 (E)(3)(d)]. Yet, the regulations do not appear to limit the number of clients an individual guardian can represent.

While the regulatory caps would appear to be intended to limit the amount of funding that professional guardians can receive per client, they also appear to provide an incentive to guardians to increase the number of clients they provide services to.

Based on those regulatory caps, we have calculated that Sloan was paid for providing guardianship services to at least 44 clients in Fiscal 2016. The Arc of Bristol County would have had at least 139 clients in that year. When guardians represent large numbers of clients, the ability of those guardians to act in their clients’ interest would appear to decline.

Moreover, the guardianships for which DDS has paid Sloan appear to be only a portion of the probate-court-related work that Sloan does.

Court records show that Sloan has been involved as a guardian, guardian ad litem, attorney, or as a “Rogers Monitor” for incapacitated persons in 118 cases in four separate counties between a seven-year period from Fiscal 2009 to 2015. That includes 14 persons for whom he was appointed as a Rogers Monitor, 75 persons for whom he was appointed as an attorney, 19 cases in which he was appointed as a guardian ad litem, and six cases in which he was appointed as a guardian.

Those six cases in which Sloan was appointed as a guardian appear to be in addition to our estimated 44 cases in which Sloan has been paid by DDS to be a guardian.

An annual client care plan filed in Worcester Probate and Family Court by Sloan does appear to raise questions about the amount of time Sloan spent representing a DDS client from May 2016 to May 2017.

Sloan described the client in the care plan as mildly developmentally disabled and as residing in a group home. Asked on the form to describe the “nature and frequency” of his visits with the client and his caregivers, Sloan stated only that he visited the client and his care givers “at least regularly, and have regular phone and email contact with his residential and day program staff.”

However, stating that he had visited his client “at least regularly” does not either specify the frequency of the visits nor describe their nature.

Sloan’s care plan report contained no critical remarks about the client’s care. He stated that the man’s needs “are being met in his current residential placement,” and that he was attending “an appropriate day program.”

DDS appears to have no centralized accounting system for paid guardians

In a May 10 Public Records law request, we asked DDS for information on the number of clients each paid guardian in its system had and the number of hours the guardians spent with their clients. In a response later that month, a DDS assistant general counsel stated that providing information on the number of clients and hours spent by guardians would require DDS to collect invoices from “multiple DDS offices,” which would take at least 30 hours of “search and collection time” for each of four regional offices. At a cost of $25 per hour, that would cost us at least $3,000, the assistant general counsel’s letter said.

In a subsequent letter sent to us in June, the assistant general counsel stated that it would take an estimated 14 hours of staff time to identify the invoices submitted in Fiscal 2016 from just one guardianship entity — the Arc of Bristol County.

The apparent difficulty that DDS has in locating invoices for payment from guardians in its system raises questions about the adequacy of its internal financial controls, in our view. The DDS central office does not even keep a record of the number of clients each of its guardians represents, according to the assistant general counsel’s May letter.

PriceWaterhouseCoopers notes the importance of centralized, or at least standardized internal controls in large nonprofit institutions such as colleges and universities. We believe a large public agency such as DDS should also have a centralized internal control system, and DDS may lack that with regard to the guardians it employs.

No response from the CPCS

On May 10, we also filed a request with the Committee for Public Counsel Services (CPCS) for a list of attorneys who are selected for appointment to represent clients of the DDS who are subject to guardianship, from Fiscal Year 2013 to the present.

As part of our information request, we asked for a list of the total annual payments made the attorneys from Fiscal 2013 to the present, and the total hours spent each year by those attorneys representing and visiting their clients.

We did not receive a response from the CPCS to our information request. We contacted the state Supervisor of Public Records with regard to the matter and were told that the CPCS is considered to be a part of the judicial branch of state government, which is not subject to the Public Records law.

DDS/Probate system needs reform

As noted, we see a potential conflict of interest in allowing DDS to recommend and pay guardians to represent people in the agency’s care. Along those lines, we are concerned that DDS has in a number of cases recommended attorneys, corporate providers, and other unrelated parties as guardians of individuals over the objections of family members of the individuals.

Also, in light of the increasing amounts paid to guardians by DDS, we are concerned that there is a potential for inadequate representation when paid guardians have large numbers of clients. Yet the payment system for guardians, in particular, appears to encourage those professional guardians to take on more and more clients.

We are also concerned that the system encourages DDS-paid guardians and CPCS attorneys to side together against the interests and wishes of families and individuals caught up in that system.

We think reform of the DDS/probate system is sorely needed, particularly with regard to payment of guardians and other financial practices. Those reforms should make the system more responsive to families, more transparent, and more accountable.

A public guardian may be the answer to many of these issues and problems, but, as noted, we think the public guardian should be just that — public. In the meantime, we urge the Judiciary Committee to finally vote to approve H. 887, which would boost the rights of families in the system by requiring probate judges to presume parents to be suitable guardians.

We will look further into these issues as we advocate for reform of the DDS/probate system.