Archive

Supported Decision Making bills give key role to state’s banking lobby

A redrafted version of Supported Decision Making (SDM) legislation, which appears to be close to enactment in the state Legislature, would give a major banking lobbying organization a key role in implementing SDM in Massachusetts.

The latest SDM bills (H.4924 and H.4949), which are actually identical drafts, have been sent to the House Rules and House Ways and Means Committees respectively, and either one of those bills appears to be a step away from enactment on the House and Senate floors.

Each bill specifies in the latest redraft that the Massachusetts Bankers Association would be involved both in developing a training program on the rights and obligations of SDM supporters, and in studying the feasibility of a state registry of all existing SDM agreements in the state.

SDM appears in our view to hold a potential to overturn guardianships of persons with intellectual and developmental disabilities (I/DD).

The legislation would authorize written agreements to replace guardians of persons with I/DD with informal teams of “supporters” or advisors. The supporters would provide those individuals with “decision-making assistance” about their care and finances.

On August 15, I sent emails to the Senate president, House speaker, and chairs of the Children, Families, and Persons with Disabilities Committee, Judiciary Committee, Rules Committee, and House Ways and Means Committee, expressing concern that the redrafted legislation contains a number of flawed provisions.

In a subsequent email last week (August 22), I sent a follow-up email to the co-chairs of the Children and Families Committee, arguing that the legislation also fails to address a potential conflict of interest involving the Mass. Bankers Association.

We maintain that the redrafted legislation would also introduce conflicts between SDM supporters and guardians; does not direct the probate court to resolve those conflicts; and does not direct the Disabled Persons Protection Commission (DPPC) to enforce a provision against coercion in signing SDM agreements. The legislation also does not provide any means of enforcing a new provision against conflicts of interest held by SDM supporters.

Mass. Bankers role

In an emailed response on August 20 to my first email, State Representative Jay Livingstone, House chair of the Children and Families Committee, maintained that the Mass. Bankers Association was added to the legislation because, “Financial institutions may be requested to accept the (SDM) agreements. The Mass. Bankers Association’s expertise may be helpful to represent those interests,” he added.

The Bankers Association is one of five non-governmental organizations given roles by the legislation in developing SDM, including the Arc of Massachusetts, the Disability Law Center, the Mass. Medical Society, and the Mass. Health and Hospital Association.

Livingstone also responded to a number of my other concerns, as I’ll discuss below. Unfortunately, our concerns about the legislation have not been assuaged.

With regard to the Mass. Bankers Association, we are concerned that banks and other financial organizations may have interests in financing or investing in the development of care facilities or corporate provider organizations, and that those financial interests could then assume a prominent role in SDM training programs or even agreements under the legislation. There is no provision in the legislation to prevent conflicts of interest involving banking, investment firms, or other financial interests in SDM arrangements.

For instance, the Mass. Bankers Association listed (H.4977), which will provide millions of dollars to finance Accessory Dwelling Units (ADUs), as a bill it was tracking this year. The bill has since been signed into law. The Arc of Massachusetts describes the development of ADUs as “one of its priorities over four sessions.” ADUs may well be a subject of consideration by SDM supporters.

We think it would be more appropriate to select a neutral individual who might be a faculty member of a university business school or economics department as an SDM training consultant, rather than selecting a member of the Mass. Bankers Association.

Major changes to Uniform Probate Code

Both SDM bills (H.4294 and H.4949) were reported favorably late last month by the Children, Families, and Persons with Disabilities Committee and are now in the House Rules and House Ways and Means Committees respectively. This legislation would make significant changes to the Massachusetts Uniform Probate Code (M.G.L. c. 190B), and yet the legislation has not been voted on favorably by the Judiciary Committee.

We are concerned that this redrafted legislation, which has not had a public hearing, could be enacted without a roll call vote in informal House and Senate sessions at any time.

Sets up conflict between SDM supporters and families and guardians

Under the redrafted legislation, it appears that an individual under a full guardianship could also sign an SDM agreement. In that case, we asked the legislators, what would the resolution process be if there were a dispute between the SDM team and the guardian?

In his August 20 response, Rep. Livingstone stated that, “Once an individual becomes subject to a full or plenary guardianship, they could not sign an SDM agreement. An SDM agreement is an alternative to guardianship.“

But that does not appear to be the case. There doesn’t appear to be any language in the legislation that would preclude signing an SDM agreement if there is a full or plenary guardianship.

At another point in his response, in fact, Rep. Livingstone stated that, “If the (probate) court that created the guardianship left a SDM agreement in place in whole or in part, the court should work out the roles and responsibilities of each. If there was a conflict (between a guardian and SDM supporters), the parties could go back to court to resolve the issues if they could not work them out themselves.”

However, as I replied to Livingstone, the legislation doesn’t require the court to work out the roles and responsibilities of each party. Further, having the parties “go back to court to resolve the issues” would automatically place the guardian at a disadvantage, in our view, if, as is likely, the supporters would outnumber the guardian in any court proceeding.

Questionable access to medical records

The legislation states that an intellectually disabled “decision maker” may provide a supporter with access to their medical records, including confidential health information, and with access to psychological, financial and other records. The legislation later states that the SDM agreement must “specifically reference” a supporter’s access to medical records etc.

To us, this raises the question: If the decision maker is under a full or plenary guardianship, why would it be necessary for SDM supporters to have access to these records unless the supporters’ authority were equal or greater than the guardian’s authority?

Questions about confidentiality

In granting access to confidential records to SDM supporters, the legislation states that a supporter “shall keep confidential any information obtained in the process of assisting the decision-maker.”

To us, this raises the question: Does this provision require a supporter to decline to disclose such information to either the guardian or to other supporters?

Livingstone responded that an individual supporter would be required to keep such information completely confidential “unless directed to (reveal it) by the decision-maker.”

This is a particularly troubling provision in that it could be used by SDM supporters to marginalize family members or guardians by keeping them in the dark regarding important aspects of an individual’s health or medical care.

Weak conflict of interest provision

The redrafted legislation states that a supporter “shall not participate in any life decision in which they have a conflict of interest.” This includes, the legislation states, “any decision in which the supporter, his or her immediate family or partner, a business organization in which he or she is serving as officer, director, trustee, partner or employee has a financial interest or other direct and substantial interest in the outcome.”

Such a provision is better than nothing, which was the case under previous versions of the SDM legislation. But even under this provision, an employee of a provider serving the individual could nevertheless serve as an SDM supporter and participate in life decisions in which the provider doesn’t have a direct financial interest.

In our view, this provision does not fully protect individuals with I/DD against conflicts of interest. The legislation doesn’t provide for enforcement of this provision.

Also, whether a specific conflict of interest exists in a particular matter could be open to interpretation. We believe employees of providers that offer services to SDM “decision makers” should not be allowed to participate in SDM agreements period.

No enforcement of anti-coercion provision

The legislation states that “evidence of undue influence or coercion in the creation or signing of a supported decision-making agreement shall render the supported decision-making agreement invalid.”

But who would determine whether there was evidence of this?

Livingstone responded that, “An interested party would need to report alleged undue influence or coercion in an SDM agreement’s creation or signing to the Disabled Persons Protection Commission, the Elder Abuse Prevention Hotline or the court for any further action.”

The problem is the legislation does not state that the Disabled Persons Protection Commission (DPPC) should investigate allegations of undue influence or coercion in the signing of an SDM agreement.

The DPPC’s enabling statute (M.G.L. c. 19C) requires the DPPC to investigate allegations of abuse or neglect that causes significant physical or emotional injury. The DPPC’s regulations (118 CMR 2.02) state that serious emotional injury can result from coercion; but it is unlikely that the regulations contemplate the type of coercion referred to in the SDM legislation.

The often subtle coercion that would be involved in the signing of an SDM agreement would be unlikely, or at least would not necessarily result in emotional distress to the signer. As a result, even if such an allegation of coercion was made to the DPPC, it isn’t clear that the agency would be statutorily required or authorized to investigate it.

Similarly, there is no way to enforce other feel-good provisions in the legislation, such as one stating that a supporter must “respect the values, beliefs, and preferences of the decision-maker, act honestly, diligently, and in good faith; act within the scope identified by the decision-maker, (and) support and implement the direction, will, and preferences of the decision-maker.”

Termination provision unworkable for persons who are unable to communicate

The legislation states that the decision-maker “may amend or terminate a supported decision-making agreement at any time…”

But what would the process be for termination if the decision-maker were unable to communicate?

Livingstone stated that, “If the decision-maker became incapacitated while the SDM agreement was valid, the bill provides that the agreement would be terminated.”

The problem is that “incapacitation” is not defined in the legislation. Any individual under guardianship is considered under the Probate Code to be incapacitated (see M.G.L. c. 190B, s. 5-303). This, in fact, goes to a key problem we have repeatedly identified with the SDM legislation. The legislation does not provide a standard level of capacity of an individual below which SDM would not be feasible.

Additional burden of proof

As we have repeatedly pointed out to the legislators, all of the versions of the SDM legislation would add to the burden of proof that a petitioner already faces in probate court in order to become a guardian. Thus, we think that this legislation may predispose probate court judges to deny guardianship petitions in favor of SDM agreements.

The legislation specifically would require anyone petitioning in probate court to become a guardian to state why a more limited guardianship or an SDM agreement was “inappropriate.”

Perhaps the major concern we have also repeatedly raised about the SDM legislation is, as noted, that it doesn’t specify a level of functioning or decision-making capacity below which an SDM arrangement would not be considered feasible. There is no consideration in the legislation as to whether persons with low levels of cognitive functioning are capable of making and appreciating life-altering decisions.

As a result, under the SDM legislation, anyone can sign an SDM agreement, no matter how low their cognitive functioning might be, and then be labeled the “decision maker” in that agreement. That aspect of the legislation alone shows that it is not based in reality.

For all of these reasons, we hope lawmakers do not enact this legislation in the remainder of the current legislative session. SDM may work for some high-functioning individuals. But it needs to go back to the drawing board in Massachusetts.

SDM legislation once again close to final passage in questionable procedural move

Legislation that would authorize Supported Decision Making (SDM) as an alternative to guardianship of persons with intellectual and developmental disabilities (I/DD) in Massachusetts is once again close to final passage in the state Legislature.

This time, the circumstances surrounding the legislative process involving the bill are particularly troubling.

SDM involves enacting written agreements to replace guardians of persons with I/DD with informal teams of “supporters” or advisors. The supporters then provide those individuals with “decision-making assistance” about their care and finances.

On July 29, with two days to go in the formal 193rd legislative session, the Children, Families, and Persons with Disabilities Committee referred two newly revised, identical SDM bills — H.4924 and H.4949 — to the Rules Committee.

Although the 193rd legislative session is now formally over, we understand that either or both of the redrafted bills can be referred at any time until the end of the year to either the House or Senate floor for final enactment. Once referred, the legislation could be enacted in “informal sessions” unless there is an objection from a lawmaker.

During informal sessions, there are usually only a few legislators present, and no roll call votes are taken.

Yet, the redrafted legislation appears to make major changes to the Massachusetts Uniform Probate Code (M.G.L. c. 190B), a set of provisions governing the probate court system.

Prior to July 29, the Children and Families Committee had delayed taking action on an earlier version of the legislation for more than a year.

In our view, guardianship is the most important legal protection family members have to ensure adequate care and services for their loved ones with I/DD.

In an email I sent last week (August 8) to key legislators, I said that legislation imposing arrangements that weaken guardianship also weakens the decision-making rights of families.

I noted that the redrafted legislation doesn’t address specifc oncerns we had previously raised about SDM with those legislators. While SDM may be appropriate for high-functioning individuals, it may expose lower functioning persons to financial exploitation and reduce the input family members have over their care and services.

Arrangements that weaken guardianship further violate the spirit of the federal Developmental Disabilities Assistance and Bill of Rights Act, which states that family members of persons with I/DD are the “primary decision-makers” in their care and services.

No vote by the Judiciary Committee

In addition to the lack of a roll call vote if the redrafted SDM bills are now taken up in the House or Senate, it appears the bills have not been voted on by the Legislature’s Judiciary Committee. The Judiciary Committee has jurisdiction over legislation pertaining to the courts in Massachusetts and the Probate Code.

Also, there has been no public hearing on the redrafted legislation, which appears to be substantially different from an earlier version of the measure. The Children and Families Committee did hold a public hearing on the earlier version in September 2023.

A staff member of the Children and Families Committee told us that the Judiciary Committee was involved with the Children and Families Committee in drafting H.4924 and H.4949. However, there is no indication on the Legislature’s website that the redrafted legislation was actually voted on favorably by the Judiciary Committee.

Committee co-chair says “plenty of time” for our concerns to be considered

In a response to my August 8 email, Representative Jay Livingstone, House chair of the Children and Families Committee, maintained that, “There is plenty of time for this bill and your (COFAR’s) comments to be considered.”

We hope that is the case, although we had raised concerns about the SDM legislation with the Children and Families Committee last year.

Livingstone also said there was “still a possibility” of a roll call vote on the redrafted legislation this year because the Senate president and House speaker have agreed to call a special session at some point before the end of the year. Nevertheless, it isn’t clear whether the SDM bills would be taken up during that special session if they are enacted this year.

Livingstone further acknowledged that the Judiciary Committee has not voted on either H.4924 or H.4949.

Redrafted legislation raises questions

In one respect, we think the redrafted legislation might be better than the earlier version of the measure.

Apparently based on a concern we raised last year, the redrafted legislation (H.4924 and H.4949) would prohibit an SDM supporter from having a conflict of interest involving their employer.

However, it isn’t clear that the redrafted legislation would completely rule out human services provider employees from serving as SDM supporters. Those individuals would be prohibited only from participating in specific “life decisions” in which they or their employers had a financial interest.

Moreover, we think the redrafted legislation as a whole would still weaken guardianship because it would set SDM up in the Probate Code as an alternative to guardianship. Under the redrafted legislation, anyone petitioning in probate court to become a guardian would have to state why either a more limited guardianship or an SDM agreement was “inappropriate.”

That SDM provision would add to the burden of proof that a petitioner already faces in probate court in order to become a guardian. Yet, an SDM agreement itself apparently doesn’t require similar court approval. Overall, we think that this legislation may predispose probate court judges to deny guardianship petitions in favor of SDM agreements.

Another concern we have about the SDM legislation is that it doesn’t specify a level of functioning and decision-making capacity below which an SDM arrangement would not be considered feasible. There is no consideration in the legislation as to whether persons with low levels of cognitive functioning are capable of making and appreciating life-altering decisions.

For all of those reasons, we think this is not the time to enact this legislation. We hope legislative leaders will recognize the need to go back to the drawing board in the next legislative session, and address the concerns we have raised.

Healey targets state-operated group homes for cut in proposed FY ’25 funding

In signing a $58 billion state budget this week for the newly begun Fiscal Year 2025, Governor Maura Healey has cut $401,000 in proposed funding for state-operated group homes.

That was one of two cuts that Healey made in Department of Developmental Services (DDS) line items in the budget plan sent to her by the Legislature. The governor also cut $1 million in proposed funding for the Autism Division.

Left untouched by Healey was $1.69 billion in funding for DDS’s separate corporate provider-run group home line item, and $390 million in a separate reserve fund for the providers.

Healey’s cut in proposed funding for the state-operated group homes still allows for a 4% increase in the funding of that line item over the previous fiscal year. But that increase will now be $2.4 million less than the increase the governor herself had proposed when she submitted her budget to the Legislature in January.

The Legislature itself had cut Healey’s proposed funding of the state-operated group homes by $2 million. Healey has now reduced that amount by an additional $401,385.

It’s unclear what the impact will be of the lowered funding increase for the state-run homes and whether it might result in cuts in staffing. It is also unclear why Healey targeted just the state-operated group homes and the Autism Division for cuts out of DDS’s total $2.9 billion budget.

Healey stated with regard to the state-operated group home line item cut that she was reducing it to $330.7 million, which is “the amount projected to be necessary.” In signing the budget, she said that, “Due to operational efficiencies, savings will be achieved (in state-operated group homes) without impacting services to clients.”

Healey’s statement, however, did not specify what those operational efficiencies were.

We have long raised concerns that a succession of administrations has been allowing the state-operated group home system to die by attrition.

We reported yesterday, in fact, that not only do there appear to be vacancies in the state-run group home system, but DDS has now acknowledged that it doesn’t keep track of those vacancies. All of these things appear to be signs that the administration does not view state-run residential services as a viable option for thousands of waiting clients.

Healey has reportedly cited “fiscal prudence” as the reason for making a total of $317 million in cuts in the Fiscal 2025 budget prior to signing it. At the same time, however, her budget increases spending overall by 3.1% over last year’s budget.

The Boston Globe reported that Healey also cut $192 million from the MassHealth managed care program, “due, in part, to ‘anticipated utilization,’ or how much the state expects people to make use of the services.”

DDS finally acknowledges it doesn’t keep track of whether there are vacancies in state-operated group homes

For almost a year, we had been trying to clarify with the Department of Developmental Services (DDS) whether there are – and we suspect there are – continuing vacancies in the Department’s network of state-operated group homes.

Finally, in a clarification issued earlier this month in an appeal we filed with the state public records supervisor, a DDS attorney stated flatly that, “DDS does not track state-operated group home vacancies.”

While it’s helpful to know it would be a waste of time to continue to ask DDS for information it clearly says it doesn’t have, the Department’s clarification still raises a number of questions. First, why doesn’t DDS track what appears to be basic information about its state-operated group home network?

Secondly, even though thousands of people with intellectual and developmental disabilities are waiting for residential placements and other services from DDS, why would the Department not have any interest in knowing whether its state-run network has available beds for them?

One troubling answer to those questions is that the Healey administration does not view state-run residential services as a viable option for those thousands of waiting clients. This is borne out by evidence that DDS is letting the state-run system die by attrition.

DDS does not generally inform people seeking residential placements of the existence either of its network of state-run group homes or of its two remaining state-run congregate residential centers – the Wrentham Developmental Center and the Hogan Regional Center. Instead, the Department directs those people to its much larger network of state-funded group homes that are run by corporate providers.

In many cases, families have told us that when they have asked about placements in state-operated group homes, DDS has stated that there are no vacancies in such homes in their area. That is despite the now-apparent fact that DDS doesn’t actually know whether there are vacancies or not.

Ambiguous statements about information on vacancies

For close to a year, DDS provided ambiguous responses to requests we made under the Public Records Law for information on the number of vacancies in the state-operated group home network in recent years.

In September 2023, I first filed a Public Records request with DDS, asking for “the number of vacancies in the state-operated group homes each year from Fiscal Year 2019 to the present.” I also asked for data on the census, or number of residents in the state-run group-home system, and the capacity, or total number of available beds in the system.

DDS responded that it did not have “any responsive records pertaining to the number of vacancies in the state-operated group homes each year from Fiscal Year 2019 to the present.” However, the Department added in that same response that, “The Department can provide the number of vacancies in state-operated group homes as of June 30, 2023, which is 91.”

Given that the Department was both saying it didn’t have information on the number of vacancies each year, but did have that information with regard to a specific date, I appealed to the public records supervisor. The public records supervisor agreed that it was unclear whether DDS did or did not have information about those vacancies.

DDS then responded with a statement that only appeared to add to the confusion. The Department stated:

Vacancies are not tracked by the Department independently from the capacity and census data provided above. Vacancy numbers are more complicated as they are dependent on a number of real time factors, including but not limited to the temporary placement needs of individuals, staffing, and other group home demographics.

Finally, this past July 10, after I had requested information on the number of vacancies through April of this year, DDS issued the following clarification:

DDS does not have in its possession, custody, or control the state-operated group home vacancies on the specific dates requested because DDS does not track state-operated group home vacancies. (my emphasis)

One-time “exercise” to determine vacancy number

In its July 10 response, the Department also sought to explain how it had come up with the number of 91 vacancies as of June 30, 2023, despite not tracking vacancies.

DDS stated that prior to my original Public Records request in September 2023, “DDS employees participated in an exercise which resulted in identifying the approximate number of state-operated group home vacancies as of June 30, 2023.”

However, since then, “no similar exercises have been conducted,” the DDS response stated.

That explanation, however, only appears to raise further questions.

Why, for instance, did DDS attempt on one occasion, but never again, to determine the number of vacancies in its group-home network?

Based on questions like that, I filed a new Public Records Request with DDS on July 12, seeking all documents relating to the Department’s exercise, which resulted in identifying the approximate number of state-operated group home vacancies as of June 30, 2023.

DDS stated that it will provide a response to my request as of Friday of this week (August 2).

DDS data on census and capacity raise further questions about possible vacancies

Despite the lack of data about vacancies, the data DDS has provided about the census and capacity of the state-operated homes implies to us that vacancies do exist in the group-home network.

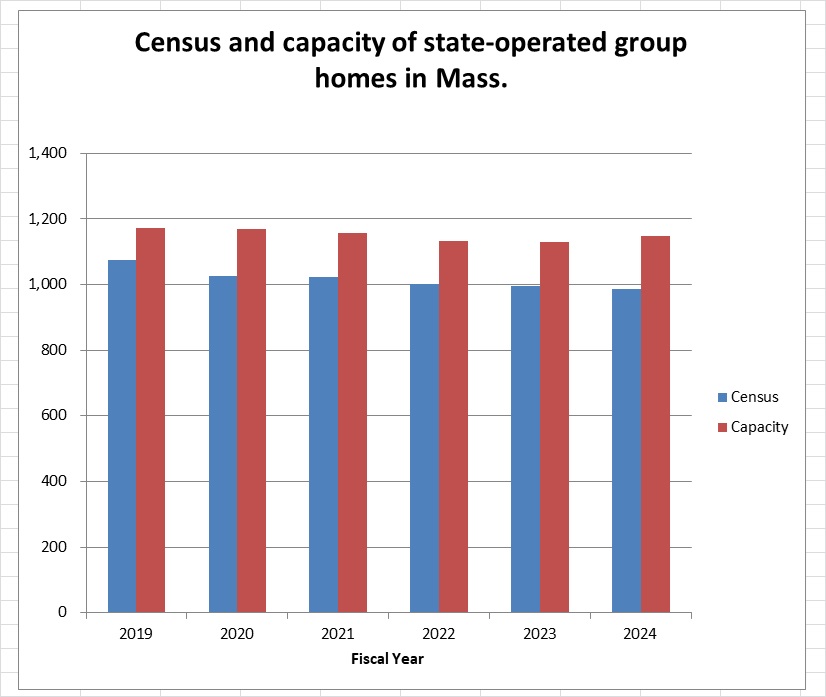

As the chart below shows, the capacity in the state-operated group home system was close to 1,150 in the just-ended Fiscal Year 2024 (as of June 30). But the total census was only 986.

The capacity as of June 30 was 16.4% higher than the census, implying that there were as many as 162 vacant beds in the state-run group home system that year.

The chart further shows that while the census (depicted by the blue columns) has steadily declined in the homes since Fiscal 2019, the capacity (red columns) declined through Fiscal 2022, and then began to rise in 2023 and 2024.

The gap between the census and capacity of the homes since Fiscal 2019 can be seen in the differences in the heights of the blue (census) and red (capacity) columns in the chart. That data appear to imply that the number of vacancies in state-operated homes has been rising since Fiscal 2022.

DDS, however, states, as noted, that it cannot confirm the number of actual vacancies in the homes because it doesn’t track them. The Department also maintains that vacancy numbers are “more complicated” than the difference between a group home’s census and its capacity.

DDS stated that the number of vacancies in group homes is “complicated” because it is “dependent on a number of real time factors, including but not limited to the temporary placement needs of individuals, staffing, and other group home demographics.”

It’s not clear to us what DDS actually means by that statement. It is not clear why the number of vacancies, for instance, would depend on staffing in the homes. In that case, it would seem that capacity would also depend on staffing. Yet, DDS was able to provide us with data on that capacity.

DDS’s reference to the temporary placement needs of individuals would appear to imply that the total census in the homes also changes over the course of the year due to temporary placements of certain individuals. Yet in that case as well, DDS was able to provide us with data on the census in the group homes.

It is unclear why DDS is able to track both the census and capacity of the homes, yet can’t or doesn’t track the number of vacancies. All three of those variables – census, capacity, and vacancies – would appear to depend on either staffing or temporary placements. Why are vacancy numbers more complicated than either census or capacity numbers?

The DDS data on the state-operated group homes raise many questions, as we’ve said. Unfortunately, DDS has repeatedly declined to answer our questions about the data.

We hope that the additional records DDS is scheduled to provide us about the one-time exercise it conducted will shed a little more light on the important vacancy question.

State lawmakers mum about abusive care providers who are avoiding placement in the Abuser Registry

Last week, we brought a concern to the attention of some 50 state legislators that there seems to be a serious problem with the state’s Abuser Registry.

New data we received from the state show that a majority of care providers whom the state has affirmed committed abuse against persons with intellectual and developmental disabilities have nevertheless been able to avoid having their names placed in the Registry.

The lawmakers to whom I sent an email on July 17 containing the link above to our report include the members of the Children, Families, and Persons with Disabilities Committee, the Mental Health, Substance Use and Recovery Committee, and the Health Care Financing Committee.

Those are the principal committees in the Legislature that deal with human services issues.

No response

To date, I haven’t received a response from any of those legislators. I followed up on my original email with a second email on July 18 to the counsel to the Children and Families Committee, and left follow-up phone messages over the past week with the co-chairs of each of the three committees.

It’s not clear to us why none of those lawmakers is willing even to say they will look into our findings. We would hope a potentially serious problem with the Abuser Registry would be of interest to all legislators.

The Abuser Registry was established under “Nicky’s Law” as a means of ensuring that individuals who have been affirmed to have committed “Registrable Abuse” cannot be hired or continue to serve in the Department of Developmental Services (DDS) system even if they don’t have criminal records.

The Registry is a database that the state and its provider agencies must check before hiring new caregiving personnel. Placement of the name of an individual in the Registry means that person is no longer eligible to work for DDS or for any agency funded by DDS.

Data show most abusers’ names not being placed in Registry

We agree that equitable use of the Abuser Registry requires balancing the protection of disabled persons from abuse with due process for accused care providers.

But as we reported, new data we received from the Disabled Persons Protection Commission (DPPC) under a Public Records Law request raise a question whether the scales in that balance might be weighted too heavily in favor of the care providers.

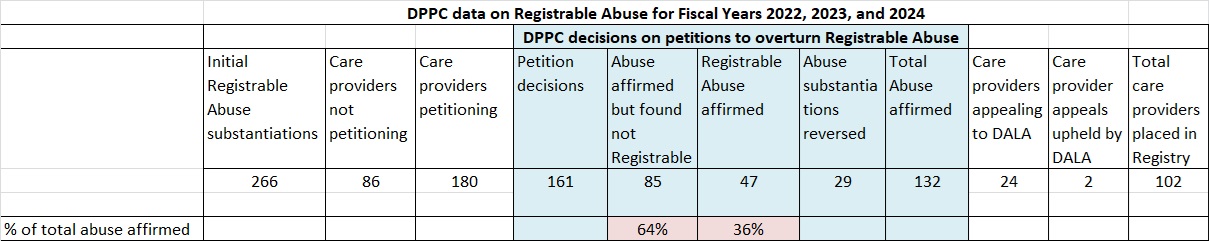

The data show that in only 36% of the cases in which DPPC affirmed initial substantiations of abuse allegations against care providers did the agency conclude that those persons’ names should be placed in the Registry. The DPPC data covered a three-year period since the database was first put into use in July 2021.

The relatively low number of care providers who have been barred from further DDS-funded employment appears to be due to provisions in the Registry regulations that appear to give wide discretion to DPPC to decide whether an individual is fit to continue to provide services.

Even if a Registrable Abuse allegation is initially substantiated against a care provider, the regulations state that the provider can petition the DPPC to argue that they should not be placed in the Registry because the alleged incident of abuse was “isolated and unlikely to reoccur,” and the provider is “fit to provide services.”

Determining whether an incident of abuse was isolated could potentially require DPPC to determine whether the individual had prior abuse allegations lodged against them. But while the regulations state that DPPC may consider information like that, the regulations don’t require DPPC to take any particular factor into consideration.

According to the DPPC data, the names of a total of 102 care providers have been placed in the Registry during the three-year period since the Registry took effect. That is 38% of the total of 266 care providers who received initial notices of substantiated Registrable Abuse in that period.

But the finding that was more concerning to us has to do with the 161 decisions the DPPC made regarding petitions that were filed by care providers to overturn initial abuse substantiations against them.

Of 132 petition cases in which the DPPC ultimately upheld the initial abuse substantiations, the agency concluded that only 47 of those substantiated abusers should have their names placed in the Registry. That is only 36% of the 132 cases.

In 85, or 64% of those cases, the DPPC determined that the abuse wasn’t Registrable, meaning the care provider should not be placed in the Registry. The agency somehow determined in those 85 cases that even though abuse had occurred, those incidents were isolated and unlikely to reoccur and the care provider was fit to provide services.

We supported the Nicky’s Law legislation, which became law in 2020, and continue to do so. But as we said in our post last week, we think the balance between safety due process needs to be adjusted.

You can help find out what’s up with our legislators

Are our legislators who are entrusted with considering and voting on matters affecting the lives of some of the most vulnerable members of our society satisfied with the Registry’s record after three years? If they are satisfied with it, why not say so? If they aren’t satisfied, why not say that?

Below is a list of the legislators whom I emailed last week expressing our concern about the Registry. Lawmakers who serve on more than one of the committees listed below are listed only once.

If any of these legislators represents your district, please feel free to email them and forward this link to our previous post, even though they should already have it. (Don’t feel you have to email more than your own senator or representative, or more than one or two of the co-chairs of the three committees. We would suggest that you email one legislator at a time.)

Ask for a response, and, if you get one, please let us know what they have to say.

Children, Families, and Persons with Disabilities Committee

Sen. Robyn Kennedy, co-chair, Robyn.Kennedy@masenate.gov

Rep. Jay Livingstone, co-chair, Jay.Livingstone@mahouse.gov

Sen. Becca Rausch, vice chair, Becca.Rausch@masenate.gov

Rep. Jessica Giannino, vice chair, jessica.giannino@mahouse.gov

Sen. Lydia Edwards, lydia.edwards@masenate.gov

Sen. James Eldridge, James.Eldridge@masenate.gov

Sen. Paul Mark, Paul.Mark@masenate.gov

Sen. Patrick O’Connor, Patrick.OConnor@masenate.gov

Rep. Rita Mendes, Rita.Mendes@mahouse.gov

Rep. Michelle Ciccolo, michelle.ciccolo@mahouse.gov

Rep. Adrianne Ramos, Adrianne.Ramos@mahouse.gov

Rep. Carol Doherty, carol.doherty@mahouse.gov

Rep. David LeBoeuf, david.leboeuf@mahouse.gov

Rep. Natalie Higgins, Natalie.Higgins@mahouse.gov

Rep. John Moran, john.moran@mahouse.gov

Rep. Donald Berthiaume, Donald.Berthiaume@mahouse.gov

Rep. Alyson Sullivan, alyson.sullivan@mahouse.gov

Mental Health, Substance Use and Recovery Committee

Sen. John Velis, co-chair, john.velis@masenate.gov

Rep. Adrian Madaro, co-chair, Adrian.Madaro@mahouse.gov

Sen. Julian Cyr, vice chair, julian.cyr@masenate.gov

Rep. Michelle DuBois, vice chair, Michelle.DuBois@mahouse.gov

Sen. Nick Collins, Nick.Collins@masenate.gov

Sen. Brendan Crighton, brendan.crighton@masenate.gov

Sen. John Keenan, John.Keenan@masenate.gov

Rep. Sally Kerans, Sally.Kerans@mahouse.gov

Rep. Christopher Markey, Christopher.Markey@mahouse.gov

Rep. Michael Kushmerek, Michael.Kushmerek@mahouse.gov

Rep. Simon Cataldo, Simon.Cataldo@mahouse.gov

Rep. Tram Nguyen, tram.nguyen@mahouse.gov

Rep. Kate Donaghue, Kate.Donaghue@mahouse.gov

Rep. Susannah Whipps, Susannah.Whipps@mahouse.gov

Rep. Steven George Xiarhos, Steven.Xiarhos@mahouse.gov

Health Care Financing Committee

Sen. Cindy Friedman, co-chair, Cindy.Friedman@masenate.gov

Rep. John Lawn, co-chair, John.Lawn@mahouse.gov

Sen. John Cronin, vice chair, John.Cronin@masenate.gov

Rep. Kathleen LaNatra, vice chair, kathleen.lanatra@mahouse.gov

Sen. Paul Feeney, paul.feeney@masenate.gov

Sen. John Keenan, John.Keenan@masenate.gov

Sen. Jason Lewis, Jason.Lewis@masenate.gov

Rep. Brian Murray, Brian.Murray@mahouse.gov

Rep. Steven Ultrino, Steven.Ultrino@mahouse.gov

Rep. Christine Barber, Christine.Barber@mahouse.gov

Rep. Lindsay Sabadosa, lindsay.sabadosa@mahouse.gov

Rep. Patricia Duffy, Patricia.Duffy@mahouse.gov

Rep. Kip Diggs, Kip.Diggs@mahouse.gov

Rep. Jack Lewis, Jack.Lewis@mahouse.gov

Rep. Christopher Worrell, Christopher.Worrell@mahouse.gov

Rep. Hannah Kane, Hannah.Kane@mahouse.gov

Rep. Mathew Muratore, Mathew.Muratore@mahouse.gov

Rep. F.J. Barrows, fred.barrows@mahouse.gov

Thanks!

Even after affirming abuse, DPPC places care providers in Abuser Registry only 36% of the time

When an “Abuser Registry” was authorized in Massachusetts with the enactment of “Nicky’s Law” in 2020, we joined many others in welcoming it as a major step forward in ensuring adequate and safe care for persons with intellectual and developmental disabilities.

Under the law, the names of caregivers against whom abuse and neglect allegations are substantiated are placed in the Abuser Registry — a database that the state and its provider agencies must check before hiring new personnel. Placement of the name of an individual in the Abuser Registry means that person is no longer eligible to work for the Department of Developmental Services (DDS) or for any agency funded by DDS.

Equitable use of the Abuser Registry requires balancing the protection of disabled persons from abuse with due process for accused care providers.

But new data we have received from the Disabled Persons Protection Commission (DPPC) under a Public Records Law request raise a question whether the scales in that balance might be weighted too heavily in favor of the care providers.

The data show that in only 36% of the cases in which DPPC affirmed initial substantiations of abuse allegations against care providers did the agency conclude that those persons’ names should be placed in the Registry.

The DPPC data covered a three-year period since the database was first put into use in July 2021.

The chart below summarizes our analysis of the DPPC data.

The Registry statute and regulations differentiate between individuals who are referred to as “caretakers” and those who are “care providers.” Only names of care providers can be placed in the Registry.

A care provider is a person who is employed by either DDS or an agency that contracts with DDS to provide services to persons with intellectual or developmental disabilities. Care providers can include volunteers.

If DPPC initially substantiates an abuse allegation and determines that the abuser is a care provider, DPPC notifies that individual of a substantiated finding of “Registrable Abuse.”

Caretakers, who include family members and others persons who are not employed by DDS or its contractors, can be investigated by DPPC and DDS for abuse; but they are not subject to placement in the Registry.

DDS and its contracting service agencies must check the Registry prior to hiring care providers.

As part of the effort to ensure due process, the Registry statute and regulations allow care providers, against whom Registrable Abuse allegations have been initially substantiated, to file petitions with DPPC to prevent their placement in the Registry.

The DPPC data show that during the three-year period since the inception of the Registry, DPPC upheld initial abuse findings involving 132 care providers who had filed petitions challenging those substantiations; yet the agency determined that only 47 of those care providers should have their names placed on the Registry. In 85 of those cases, the agency concluded that the care providers were still fit to continue providing services.

The relatively low number of care providers who have been barred from further DDS-funded employment appears to be due to provisions in the Registry regulations that appear to give wide discretion to DPPC to decide whether an individual is fit to continue to provide services.

Even if a Registrable Abuse allegation is initially substantiated against a care provider, the regulations state that the DPPC can decide not to place that individual in the Registry if the alleged incident of abuse is found to be “isolated,” or if the provider is found to be “fit to provide services.”

Determining whether an incident of abuse was isolated could potentially require DPPC to determine whether the individual had prior abuse allegations lodged against them. But while the regulations state that DPPC may consider information like that, the regulations don’t require DPPC to take those particular factors into consideration.

Confirmed abusers not necessarily placed in the Registry

When a care provider petitions DPPC to overturn an initial finding of Registrable Abuse, one of three things can happen. DPPC can:

- Determine that the abuse substantiation was not supported by a preponderance of the evidence. In that case, the substantiation finding is reversed, and the care provider’s name is not placed in the Registry.

- Uphold the abuse substantiation, but determine that the incident was isolated and unlikely to reoccur, and that the care provider is fit to provide services to persons with disabilities. In that case, referred to as a “split decision,” the care provider’s name is similarly not placed in the Registry.

- Determine that the substantiation is supported by a preponderance of the evidence and that the care provider has not shown that the incident was isolated or that they are fit to continue to provide services. In that case, the care provider’s name is placed in the Registry.

If a care provider does not file a petition to overturn a Registrable Abuse substantiation, their name is automatically placed in the Registry.

In our view, the second outcome above involving consideration of care provider petitions is problematic. How does DPPC determine whether an incident of abuse is unlikely to reoccur or that a caregiver is fit to continue to provide services?

Under the regulations, there are a number of factors that DPPC may consider, including whether the care provider “received training relevant to the incident at issue”; the care provider’s employment history in working with individuals with disabilities; prior instances of similar conduct by the care provider; any statements or communication regarding the care provider’s work history and fitness to provide services; and whether the care provider’s conduct “could reasonably be addressed through training, education, rehabilitation, or other corrective employment action and the care provider’s willingness to engage in said training, education, or other corrective employment action.”

But as noted, the regulations say only that each of these criteria may be considered by the DPPC, not that they must be considered. At least some of these criteria also seem vague and potentially easy to establish.

So it’s not necessarily the case that DPPC, for instance, would consider prior instances of similar conduct in determining whether to approve or deny a petition to overturn a Registrable Abuse substantiation. As a result, it seems that the regulations may provide care providers with a relatively easy path to avoid placement in the Registry.

The DPPC doesn’t agree with our conclusions. An attorney with the DPPC defended the Registry statute and regulations, saying they were “drafted with input from various stakeholders to balance the safety of persons with I/DD (intellectual and developmental disabilities) and the due process rights of care providers.”

The DPPC attorney added that the agency “believes that the seven enumerated but non-exhaustive factors in (the regulations) are neither vague nor do they present an ‘easy path’ for exclusion from the registry. Each Petition is carefully analyzed based on its unique circumstances.”

Our analysis of the data

We analyzed DPPC data concerning Registrable Abuse for Fiscal Years 2022, 2023, and 2024, the years that the Registry has been in existence.

The DPPC data show an average of 13,500 allegations of abuse were filed each year, but DPPC “screened in” only an average of 2,400 of them per year for investigation over the three-year period. Of those screened-in allegations, DPPC and DDS initially substantiated Registrable Abuse involving 266 care providers.

Of those 266 care providers who had Registrable Abuse substantiated, 180, or 67%, filed petitions with DPPC, contesting the substantiations. The names of the remaining 86 providers, who didn’t contest the abuse substantiations, were automatically placed in the Registry.

The data show that over the three-year period, DPPC issued decisions in 161 of the 180 petition cases. As of June 17 of this year, 19 of those cases were still pending.

According to the data, DPPC upheld the initial abuse substantiations in 132, or 82%, of the 161 petition decisions. However, in 85, or 64%, of the 132 cases, the agency determined that the abuse wasn’t Registrable, meaning the care provider was fit to continue providing services and should not be placed in the Registry. Those were so-called split decisions.

In only 47 of the 132 cases, in which abuse substantiations were upheld, did DPPC determine that the care providers’ names should be placed in the Registry.

The data further show that a total of 24 care providers, against whom DPPC had affirmed Registrable abuse, exercised their additional right under the regulations to appeal to the Division of Administrative Law Appeals (DALA), an independent state agency that conducts adjudicatory hearings. DALA overturned DPPC’s decisions in only 2 of those 24 appeals.

According to the data, a total of 102 names of individuals were placed in the Registry during the three-year period. That is 38% of the total number receiving initial notices of substantiated Registrable Abuse.

We think the DPPC regulations need to be made more stringent to ensure that while due process should remain for care providers who are accused of abuse, unfit providers do not continue to work in the DDS system.

In considering care provider petitions, DPPC should be required to consider all of the enumerated factors in the regulations, particularly a care provider’s previous incidents of abuse and previous work history. Those factors are critically important in determining whether a given incident of abuse is isolated or not. Leaving it to DPPC’s discretion whether to consider those factors invites distrust of the agency’s decisions.

We also think DPPC should be required to consider impact statements from the victims and their families.

Registry established because of paucity of criminal convictions

Prior to the establishment of the Registry, caregivers in Massachusetts were prevented by law from working in DDS-funded facilities only if they had prior criminal convictions. However, even when abuse against persons with developmental disabilities is substantiated by agencies such as the DPPC, it does not usually result in criminal charges.

Thus, the Abuser Registry was intended to ensure that individuals who have been affirmed to have committed Registrable Abuse cannot be hired or continue to serve in the DDS system even if they don’t have criminal records.

We believe that in this respect, the establishment of the Abuser Registry was a major step forward in the care of persons with intellectual and developmental disabilities. But we think the balance between safety of those individuals and due process that is afforded to their care providers needs to be adjusted.

DDS and provider deny request to use anti-choking device in group home

It was a scary moment for Suzanne Marshall when she learned that her brother Gary had nearly choked to death while eating in his group home in Lexington in January.

Gary uses a wheelchair and can’t assist in efforts to administer the Heimlich maneuver or CPR on him.

As Gary was choking, a staff member first applied several sharp blows to his back, which did not dislodge the food particle. Then a male staff member dragged him out of his wheelchair, placed him on the floor and administered CPR, which successfully dislodged it.

While the episode had a fortunate outcome, Suzanne is concerned that it could happen again, and that this time, a staff member capable of getting Gary out of the wheelchair might not be available.

Suzanne noted that often at the group home, there are either only one or two female staff working. She is concerned that in this situation, a single staff person may not be strong enough to pull her brother out of his chair. He is a total dead weight, she said, and is heavy.

Then Suzanne heard about a small airway suction device, which she said has been used successfully in Gary’s day habilitation program.

Called the LifeVac, it is meant to be placed over a choking victim’s mouth and nose while air is compressed out of it, causing a vacuum. If the LifeVac is used, the victim can remain seated in their wheelchair.

Suzanne contends there is a good chance the LifeVac, or another device of similar quality, could save her brother’s life if he were to experience another choking episode and all other measures had failed. In that case, the device would do no harm even if it was also unsuccessful.

Gary, who is 68, is intellectually disabled. He has a tendency to eat too quickly, which can cause choking problems. Due to a craniotomy for cancer and subsequent chemotherapy and radiation, Suzanne said, Gary has continued to decline both physically and intellectually. She said his tendency to choke is due both to dysphasia and his intellectual disability.

Suzanne first asked the manager of Gary’s group home, which is run by JRI, whether the staff could be trained to use the LifeVac as a last resort if existing protocols for helping Gary in a future choking episode were unsuccessful. But her request was denied by JRI, so she contacted the Department of Developmental Services (DDS), which funds the provider.

On June 4, Suzanne received a reply from Meghan Allen, the DDS ombudsperson, stating that the DDS area office and the medical staff were “unable to clear the usage of a non-FDA cleared device should your brother experience another choking event.”

Allen maintained that the device “is not in common use,” and contended that it “has the potential to evacuate air from the lungs and leave the object stuck in the airway. Upon your continued interest in using LifeVac,” Allen added, “the staff did outreach and research and could not find evidence that supports its use in this setting.”

But when Suzanne looked further into the issue, she said, she found studies had recommended the LifeVac. She also found out that the FDA doesn’t clear or approve Class II suction devices, which is how the LifeVac is classified. The FDA requires only that companies that make such devices register with the agency, which the LifeVac company has done.

But none of that has swayed either JRI or DDS. They have continued to deny the use of the device in the group home.

State legislator contacted

Suzanne tried turning to State Representative Michelle Ciccolo, whose district includes Lexington, where Gary’s group home is located. Ciccolo’s legislative aide did contact DDS. But Ciccolo was apparently satisfied with DDS’s position after hearing back from Allen.

I wrote to Ciccolo on June 20, rebutting the arguments put forward by Allen. I also wrote to Allen, similarly rebutting the arguments against using the LifeVac device.

Rebutting statements that the LifeVac is not in common use and allegedly leaves objects stuck in airway

In my messages to Ciccolo and Allen, I noted that with regard to the LifeVac’s usage, the company maintains that the device has been “reviewed, purchased, and implemented” in over 7,900 schools, 330 fire departments, 230 police departments, and 45 hospitals, as well as in “numerous Emergency Response Training Centers, disability facilities, eldercare homes, medical offices, dental practices, restaurants, corporations, and churches, (and) in over one million homes across the country.”

As noted, the LifeVac is used by Gary’s dayhab program. That is, in fact, how Suzanne found out about the device.

With regard to the claim that the LifeVac device leaves objects stuck in the airway, a peer reviewed study says the opposite. The study, published in The International Journal of Clinical Skills, specifically says objects getting stuck in the airway do not constitute a risk with the device.

The study noted that after the LifeVac’s face mask is applied, “a one-way valve on the plunger generates negative pressure. On downward thrust of the plunger, air is forced out the sides of the device and not into the victim. This,” the study said, “avoids the possibility of pushing an obstructing object further into the airway.”

While risks of the LifeVac can include edema and bruising from the generated suction, the study concluded that “the benefit of saving a life clearly outweighs these small risks.”

The study recommended that the LifeVac “be available for use in settings with high risk for choking such as nursing homes and day care centers, and possibly all public eating facilities.”

Several peer reviewed studies have been highly positive about the LifeVac

As noted, Allen had further had stated that DDS and medical staff had done research, but couldn’t find evidence supporting the LifeVac’s use.

Allen didn’t describe the research she was referring to. In my messages to Allen and Ciccolo, I noted that Suzanne had provided DDS with a list of eight peer-reviewed studies, which found the LifeVac device to be highly effective.

One of the studies, published by the Frontiers journal, described self-reported data regarding the use of the LifeVac device “in adult patients with oropharyngeal dysphagia during real-world choking emergencies recorded between January 2014 and July 2020.” According to the study:

Over a 6-year monitoring period, the (LifeVac) device has been reported to be successful in the resuscitation of 38 out of 39 patients with oropharyngeal dysphagia during choking emergencies…This portable, non-powered suction device may be useful in resuscitating patients with oropharyngeal dysphagia who are choking.

To be clear, Suzanne is not suggesting that the LifeVac device be authorized to replace existing choking protocols at the group home. As noted, she has asked that the device be used as a last resort should all existing protocols fail.

We hope DDS will take another look at Suzanne’s request with regard to this device. If used as a last resort, as intended, the device will do no harm.

At best, the LifeVac will, and has, saved lives. It makes no sense to us that DDS is unwilling to make it available at least for Gary, and potentially for all clients who are prone to choking.

Does DDS really not know how many vacancies there are in its state-run group homes?

Does the Department of Developmental Services really not keep track of vacancies in its network of state-operated group homes?

That’s the question we have been asking since DDS denied our Public Records request last month for information about the number of vacancies in the residences each year for the past two years.

Earlier this week, the state’s public records supervisor agreed to consider that question as well.

In its May 15 denial, DDS stated that it did not have documents showing the number of vacancies as of the dates we requested, which included the end of Fiscal Years 2022 and 2023, and the date on which we filed the request — April 24 of this year.

Does that mean DDS doesn’t have information on vacancies on other dates? The Department’s response didn’t say.

The DDS denial also stated that, “Vacancies are not tracked by the Department independently from the capacity and census data provided.” In our request, we had asked for information each year on the census (number of residents) and capacity (total number of available beds) in the group homes.

Does DDS’s response mean that the Department doesn’t track vacancies period, or just not “independently from the capacity and census data provided?”

On May 20, we appealed DDS’s response to Manza Arthur, the state’s public records supervisor, arguing that the DDS response was “confusing and ambiguous as to whether DDS actually tracks and has records concerning vacancies in its state-run group homes.”

As we noted, “It’s hard to believe that DDS would not know or keep track of whether vacancies exist in the group home system that it directly manages.”

We added that, “We regularly hear from family members who say they are told by DDS that there are no vacancies in state-operated or provider-operated group homes in specific areas of the state when they request such placements for their loved ones.” We asked how DDS officials “can truthfully say vacancies do not exist in given areas if they don’t know or keep track of that information.”

Public records supervisor initially denies our appeal, but then agrees to reconsider her decision

On June 4, Arthur issued a decision denying our appeal, without responding to or addressing our arguments. She stated only that in a telephone conversation with her office on May 23, “the Department confirmed that it does not possess additional records responsive to …(our) request.” She then stated that she considered our appeal closed.

On Monday (June 24), we asked that Arthur reconsider her decision, saying she had not assessed the merit of any of our assertions in our appeal. We requested that she provide at least some assessment of those assertions, particularly that the Department’s statement was ambiguous as to whether it possesses any information regarding vacancies in state-operated group homes.

I received a message on Monday afternoon from Arthur’s office, saying she had agreed to reconsider her initial decision, based on our objections, and that her new decision would be made in 15 business days, which would be by July 15.

DDS doesn’t inform clients or families about state-operated group homes or ICFs

We have contended for the past few years that there must be vacancies in state-run facilities, including the group homes, because the administration is not informing people seeking residential placements of the existence of those facilities.

As a result, the number of residents in the state-run facilities has been steadily declining. This has been true not only of the group homes, but of the state’s two remaining Intermediate Care Facilities (ICFs) — the Wrentham Developmental Center and the Hogan Regional Center.

In fact, data we did receive as part of DDS’s May 15 response to our Public Records request shows that as of April 24, the census in state-run group homes had dropped 18% from Fiscal Year 2015. As of April 24, the group home census was down to 986.

That decline in the state-run group home census can be compared to the growing census in the Department’s corporate-provider-run group home system, which reached more than 8,200 residents as of Fiscal 2021.

DDS data provided on May 15 also showed that the census at the Wrentham Center was 159 as of April 24. That was down from 323 in Fiscal 2013 – a 51% drop. The census at Hogan as of April 24 was 88. That was down from 159 in Fiscal 2011 – a 45% drop.

Seeking a clarifying statement from DDS

In her initial denial of our appeal regarding the vacancies, Arthur stated that under the Public Records Law, a public employee is not required to answer questions, do research, or create documents in response to questions. But she also stated that under the Law, custodians of records in state agencies are expected to “use their superior knowledge of the records in their custody to assist requestors in obtaining the desired information.”

We subsequently argued to her that it is not clear that DDS has used its superior knowledge of the records in this case to assist us in obtaining our desired information.

We requested that the public records supervisor order DDS to clarify whether it possesses any records that indicate whether vacancies in state-operated homes exist and the number of such vacancies.

It seems to us that DDS does not want to clarify this issue. If there is indeed a growing number of vacancies in state-operated group homes, then DDS would have to explain to clients and families why they are not offering those settings as an option.

It’s more convenient to keep records that might shed light on this issue private with carefully worded statements that appear to imply that the records don’t exist.

We are hopeful that in agreeing to reconsider her initial decision, the public records supervisor recognizes that DDS has an obligation to clarify the nature of the records it possesses, and therefore won’t be able to get away with clouding the issue.

Does the state commission on the history of institutional care have a private agenda?

A year into the operation of a state commission on the history of the former Fernald Developmental Center and other state institutions, the commission members apparently have yet to discuss that history.

As a result of that and other evidence, we are concerned that the commission’s real purpose may be something else entirely.

In fact, the evidence shows the commission may be poised to recommend the closure of the last two existing state-run congregate care facilities for persons with intellectual and developmental disabilities in Massachusetts — the Wrentham Developmental Center and Hogan Regional Center.

Our concern is based on online minutes and recorded Zoom meetings of the Special Commission on State Institutions since those meetings began in June 2023. It is also based on prejudicial statements made prior to the establishment of the commission by individuals later appointed to the commission and by organizations given appointing power to the commission.

The commission’s enabling statute states that the commission will “study and report on the history of state institutions for people with intellectual or developmental disabilities or mental health conditions in the commonwealth including, but not limited to, the Walter E. Fernald state school and the Metropolitan State hospital.”

However, a provision in the statute also states, in part, that that the commission’s work “may include recommendations for… deinstitutionalization…(and regarding) the independent living movement.”

Why would a commission established to study and report on the history of state institutions also be authorized to recommend deinstitutionalization — in other words, the closure of currently existing institutions?

The minutes and Zoom recordings of the commission’s meetings thus far indicate that the major subject that appears to have been off the table for discussion has been the history of the state institutions. There simply don’t appear to have been any discussions reflected in the minutes about that history, pro or con. Instead, the discussions have been about numerous peripheral issues.

Might that lack of discussion about institutional history mean the commission has already reached its conclusions?

The commission is required to submit a report to the Legislature with its findings and recommendations by June 1, 2025.

We have repeatedly expressed concern that the commission would examine only the history of the institutions prior to the 1980s when those facilities were notorious for abuse, neglect and poor conditions. We have contended the commission would likely ignore the history of the state institutions after significant improvements to them were made and overseen by a U.S. District Court judge in the 1980s.

We reviewed the minutes and Zoom recordings of the commission’s meetings, which have been posted on line. The meetings were held on June 1, September 6, and October 20, 2023, and on January 18 and March 21 of this year.

Among the additional evidence for our concerns are that:

- No clear direction thus far appears to have been publicly provided by the commission to its consultant, the Center for Developmental Disability Evaluation and Research (CDDER), regarding the scope of the commission’s inquiry. CDDER, which is part of the UMass Medical School, will apparently be charged with writing the commission’s report.

- There has thus far been no participation on the commission, as required, by a family member of a current resident of the Wrentham Center. That appears to be the only position on the commission that has gone unfilled to date.

A family member, who did initially agree to serve on the commission, said he was told by an administration official that he couldn’t continue to serve because he lives out of state. However, nothing in the commission’s enabling statute requires family members to live in Massachusetts in order to serve on the commission.

During the legislative process to create the commission, we argued for the inclusion on the commission of family members of current residents of both Wrentham and Hogan in order to help ensure that the commission will at least focus to some extent on the high level of care currently provided in those facilities.

According to the minutes, it was only in March of this year, nine months after the start of the commission meetings, that a family member of a current Hogan resident was apparently appointed.

- Four members of the 17-member commission include Healey administration officials or designees, and an additional seven members are appointees of the governor.

The administration has been blocking admissions to the Wrentham and Hogan Centers – a policy that is leading to a steady decline in the number of residents in those facilities. We are concerned that by the time the commission is scheduled to issue its report, the cost per resident at Wrentham and Hogan will have risen to a point at which the administration will begin making a case for the closure of the centers.

Wrentham and Hogan, the state’s two remaining Intermediate Care Facilities (ICFs), provide intensive residential services and are a critical backstop for care for some of the most severely intellectually disabled residents in the commonwealth.

We are concerned that the eventual closure of Wrentham and Hogan is being planned by the Healey administration. The administration and state Legislature, in contrast, have continued to increase the budgetary line item for community-based group homes to over $1.7 billion in the current fiscal year.

Commission members have made previous prejudicial statements

Proponents of the commission made statements prior to serving on the panel that were almost uniformly negative about care at the former Fernald Center, in particular. Those criticisms of Fernald were exclusively focused on the institution’s history prior to the 1980s, and never acknowledged improvements made at Fernald and other similar ICFs after that period.

For instance, several organizations, which were authorized under the commission’s enabling statute to appoint members to the commission, signed a petition and letter to Waltham Mayor Jeannette McCarthy in December 2021 opposing a Christmas light show on the Fernald grounds because Fernald had allegedly exclusively been a site of abuse and neglect. That petition, and one prior to it the previous year, stated that:

The use of this (Fernald) site (for a Christmas light show) is both disturbing and inappropriate, given its history of human rights abuses and experimentation on children. Hosting the Greater Boston Celebration of Lights here ignores the fact that the people who lived at the Fernald School were denied holidays with their families and loved ones for generations.

It appears the minds of the signers of that letter and petition had already been made up about Fernald before the commission was created. Neither the petition or letter noted the positive transformation of Fernald starting in the 1980s, nor the opposition of many families to Fernald’s closure in 2014.

Among the signers of the 2021 petition and letter to McCarthy were four organizations that were later given authorization under the enabling statute to appoint members to the commission – the Arc of Massachusetts, Mass. Advocates Standing Strong, Mass. Families Organizing for Change, and the Boston Center for Independent Living.

A member of a fifth organization, Kiva Centers, which also signed the petition and letter to McCarthy, is also serving on the commission, according to the minutes. Kiva Centers is not specified in the enabling statute as being authorized to appoint a member to the commission.

Alex Green, one of the principal backers of the commission’s enabling statute, started the petitions against Fernald and made numerous negative statements about Fernald, including writing a commentary in November 2020 that advocated deinstitutionalization. Green was appointed to the commission by the Arc of Massachusetts.

In his commentary, Green stated:

I have no doubt that a full reckoning with disability history would have led us to create a society better than this one, where the deaths of disabled Americans — who are often still forced to live in institutional settings — are as many as the anonymous ditches bulldozed for bodies (of persons who died during the COVID pandemic) on Hart Island in New York. (Link in the original.)

Enabling statute is vague about historical scope, but specifies deinstitutionalization and ‘the independent living movement’

The commission’s unclear focus appears to be at least partly due to the vagueness of the commission’s enabling statute, which was enacted as an amendment to the state’s Fiscal Year 2023 budget. A more carefully drafted bill, (H. 4961) which would have given COFAR an appointment to the commission, died in a legislative committee in July 2022.

As noted, the enabling statute states that the commission will “study and report on the history of state institutions for people with intellectual or developmental disabilities or mental health conditions in the commonwealth including, but not limited to, the Walter E. Fernald state school and the Metropolitan State hospital.”

The statute does specify that the commission will review records of former residents of the institutions, assess records of burial locations of those residents, and try to find unmarked graves of residents. But none of those requirements describes the nature of the history the commission will study or the purpose of such a study.

A final requirement in the statute states that the commission will:

…design a framework for public recognition of the commonwealth’s guardianship of residents with disabilities throughout history, which may include, but shall not be limited to, recommendations for memorialization and public education on the history and current state of the independent living movement, deinstitutionalization and the inclusion of people with disabilities. (my emphasis)

It’s not clear what, if anything, that provision in the statute has to do with the history of the state institutions. However, the provision does appear to allow the commission to recommend deinstitutionalization, which we think could mean closures of the Wrentham and Hogan Centers.

The provision also states that the commission may issue recommendations regarding the “independent living movement.” The independent living movement is not defined, but it appears to stand in opposition to congregate care in ICFs. As such, it appears to refer to “community-based” group homes or other community-based living arrangements such as staffed apartments or staffing in private homes.

While so-called community-based care works well for many high-functioning individuals, we have maintained that ICFs remain a critically important option for persons who cannot function in the community system.

Rejected bill contained independence clause and gave COFAR appointment

The previous bill, H. 4961, which had been reported favorably by the Mental Health and Substance Abuse Committee in July 2022, was also vague about how the commission would research and report on the history of the institutions. But it had a number of provisions that would have been helpful to the commission’s charge, but which were removed in the final, budget amendment version.

The rejected bill had stated that the commission would be “independent of supervision or control by any executive agency and shall provide objective perspectives on the matters before it.” That language was taken out of the final budget version.

Also, the rejected bill stated that the commission would “assess the quality of life” of residents currently living in state institutions, including Wrentham and Hogan, and would collect testimonials from current and former residents of state institutions, including Wrentham and Hogan, as part of a human rights report. That provision was also taken out of the final budget version.

Finally, the final version of the enabling statute removed a provision in H. 4961, which would have given COFAR the authority to appoint one person to the commission. The final version of the statute, however, kept that appointing authority for the Arc and the other anti-ICF organizations mentioned earlier.

Focus on issues irrelevant to the history of the institutions

As noted, the commission’s minutes don’t appear to contain any discussion about the actual history of the institutions. Instead, the commission’s discussions appear to have focused on such things as:

- The discovery, a decade after Fernald’s closure, of records of residents that were left behind in a state of disarray on the floors of abandoned buildings on the Fernald campus.

While this is a serious issue that needs to be investigated, it has nothing to do with the history of Fernald or the other institutions while they were in operation. The fact that the Fernald records breach has been the focus of discussion in at least two commission meetings may be an indication of the vagueness of the commission’s scope of inquiry as set out in the enabling statute.

- The hiring of CDDER as the commission’s consultant.

The first commission meeting, held on June 1, 2023, contained a preliminary discussion of a plan to hire a consultant to the commission for “staffing support,” and to use $145,000 in funding allocated to the commission for that purpose.

The commission’s second meeting on September 6 included a discussion of a recommendation that the commission hire CDDER as the consultant. It still wasn’t clear what the consultant was being hired to do.

In the third commission meeting on October 20, the commission voted to hire CDDER, with discussion that CDDER would likely be writing the commission’s report to the Legislature. It doesn’t appear that the commission considered any other consultants for the job.