Archive

Family members support subminimum wages at federal online hearing

Last week, at least 17 people testified in an online hearing hosted by the U.S. Department of Labor in favor of work programs that pay subminimum wages to persons with intellectual and other developmental disabilities.

Those 17 people were primarily mothers of children with severe or profound levels of intellectual disability or autism. They were from states all over the country, and they outnumbered the five people, most of them policy analysts or corporate provider employees, who spoke against subminimum wages.

Speaker after speaker said their son or daughter, or sometimes sibling, is not able to produce at the level necessary to earn a minimum wage. Consequently, those cognitively disabled individuals are unable to get work in integrated or competitive employment settings.

I also testified on behalf of COFAR at the November 1 hearing, arguing that disabled individuals and their families have a right to choose programs that pay subminimum wages. Yet, I had the feeling that the apparent majority support for subminimum wage programs during the hearing made no difference, and that minds in DOL have been made up on this matter.

The November 1 hearing was the second of three such DOL hearings regarding subminimum wages or “Section 14(c)” programs. The first hearing was held on October 26, and the final hearing will be on November 15 at 5:30 p.m. Information about registering for the November 15 hearing is available here.

There is no question that the payment of subminimum wages has been under attack. Most, if not all, of the members of the Massachusetts congressional delegation oppose subminimum wages.

Michelle Diament of Disability Scoop wrote last month that the DOL is “reviewing” subminimum wage programs at the request of a wide range of disability advocates and policymakers, including the Government Accountability Office, the National Council on Disability, the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights and the Labor Department’s Advisory Committee on Increasing Competitive Integrated Employment.

The U.S. Department of Justice appears to have summed up the federal position last month regarding subminimum wages and congregate employment settings, stating that:

In many sheltered workshops, for example, people with disabilities perform highly repetitive, manual tasks, such as folding, sorting, and bagging, in shared spaces occupied only by other people with disabilities. They also often earn extremely low wages when compared to people with disabilities in integrated employment, resulting in stigmatization and a lack of economic independence.

It doesn’t seem to have occurred to the DOJ or the other organizations listed above that that not all people with developmental disabilities are capable of achieving economic independence. There is no recognition by these organizations that there are individuals with developmental disabilities for whom highly repetitive, manual tasks are appropriate and fulfilling.

I wish at least one of the lawmakers in the Massachusetts delegation could have listened to the parents testifying during the November 1 hearing instead of listening only to lobbyists and the corporate providers on this issue.

Carol Skelly of Fairfax, VA, for instance, said her son Patrick, 36, has an intellectual disability and autism, and “really likes doing repetitive tasks.”

Carol said her son has “no notion of money,” so a minimum wage would mean nothing to him. No one will hire him at a competitive wage, she said. “Restrictions on subminimum wages have taken important work away from people at the more severe end of the disability spectrum,” she added.

Erica Royale, the parent of a 35-year-old man with a developmental disability, maintained that eliminating subminimum wages “will be the death of sheltered workshops.” She said her son “is thrilled at the jobs he accomplishes” in his sheltered workshop, and that the work “has brought meaning to his life.”

Carissa Ross of Warren County, NJ, spoke about her own experience in a sheltered workshop. She said that when she turned 19, she suffered a stroke that left her in a coma for 27 days. She underwent rehabilitation and had to relearn how to walk and eat.

Today, she said, she is legally blind and epileptic. Because of her disabilities, she was repeatedly denied employment in competitive workplaces. But in May 2015, a nonprofit accepted her into a 14(c) day program. “The 14(c) work program saved me,” she said. “The amount of money I made didn’t matter. The purpose of life matters.”

Elizabeth Steinleitner of Allentown, PA talked about her son John who was fired from several jobs. His 14(c) program “has been a Godsend for him,” she said.

Similar assessments of the benefits of subminimum wage programs were given by Mary Miller of Wisconsin about her 30-year-old son; Stacy of Boston regarding her sister Brenda; Susan Burke about her 22-year-old son; Kenneth Eisenhower of Texas about his 22-year-old daughter; Beth Lambert of Connecticut about her 40-year-old son; Darlene Borre about her son; Jacob Caplan of New Jersey about his brother; Carol London of California about his 26-year-old son; and Karen Rubel from Chester County, PA, about her daughter.

As the federal Developmental Disabilities Assistance and Bill of Rights Act states, “Individuals with developmental disabilities and their families are the primary decision makers regarding the services and supports such individuals and their families receive.”

Policy makers at all levels of government must begin to recognize that it is those individuals with disabilities and their families who know what is best for them. They need to understand that the wishes of individuals and their family members should be paramount with regard to the care and services that government provides and funds.

DDS psychologist shortage may be causing delays in approving services

In addition to a shortage of direct care staff, the Department of Developmental Services (DDS) appears to be dealing with a shortage of psychologists who are needed to help determine eligibility for services for potentially hundreds of people each year.

Records obtained by COFAR from DDS under a Public Records Law request show that the Office for Civil Rights (OCR) with the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services investigated at least one complaint that an inordinately long delay by DDS during the past two years in processing an application for services amounted to discrimination against the applicant.

It took more than a year for DDS to determine that the applicant was, in fact, not eligible for DDS services. Under the Department’s regulations, eligibility determinations should take no longer than 60 days. The regulations state that the determination process can take an additional 60 days (or a total of 120 days) if the application is incomplete, which was apparently the case in this matter.

DDS cited “limited clinical resources”

The OCR ultimately determined that DDS had not discriminated against the applicant. However, the federal agency noted that DDS had acknowledged that the delay in processing the application was due to “limited clinical resources.”

According to the OCR report, DDS also stated that, “the departure of a full-time RET (Regional Eligibility Team) psychologist in June 2021 affected the turnaround for reviewing applications.”

COFAR is seeking additional records from DDS in order to determine the scope of the possible backlog in eligibility determinations. We initially requested the records in September after receiving a call from a parent who said she had been told the eligibility determination process in her region could take up to a year to carry out.

Under DDS regulations, the Regional Eligibility Teams consist at least one licensed doctoral level psychologist, an individual with a master’s degree in social work, and a Department eligibility specialist.

Job posting records show few hires

Our records request in September was for records concerning any backlogs or delays in processing eligibility applications, and concerning shortages of psychologists or other members of Regional Eligibility Teams.

Records provided in response so far by DDS show that the Department posted openings for psychologists on 15 occasions between July 2022 and September 2023. During that time, only two psychologists were hired, the records indicate. DDS has so far not responded to questions we submitted last week about the job posting records.

The postings were for eligibility psychologists, licensed psychologists III and IV, and regional, clinical, and senior psychologists. According to the records, the minimum salaries for those positions averaged $90,300, and the maximum salaries averaged $147,000.

Six of the job postings indicated that the hired psychologists would be involved in making determinations of eligibility for services.

OCR investigated whether delay was discrimination

According to the report by the OCR, dated June 27, on the discrimination complaint, the complainant alleged that the DDS Regional Eligibility Team had received their application for adult Community Developmental Disability (CDD) supports in January 2021. But it wasn’t until February 2022, or more than a year later, that the applicant was evaluated for his or her eligibility, the applicant alleged.

The complainant maintained that the delay prevented them from accessing benefits and care to which they were entitled. The complainant’s name was redacted in the report.

OCR is responsible for enforcing Section 504 of the federal Rehabilitation Act of 1973 and of Title II of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). DDS is required to comply with both of those statutes.

Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act states that no disabled person may be excluded or denied benefits on the basis of disability from any program receiving federal funding.

The OCR report stated that in May 2022, DDS issued an eligibility determination letter to the applicant informing them that they were actually ineligible for CDD supports as they did not meet all four criteria of the “Developmental Disability” definition.

OCR did not find noncompliance, for unclear reasons

Despite DDS’s admitted delay in processing the application, the OCR report stated that it had “not found sufficient evidence of noncompliance regarding the allegation that DDS discriminated against the complainant.” The report stated that the OCR’s determination applied only to that particular complaint.

While DDS was not cited in this case with a violation of either the Rehabilitation Act or the ADA, it is nevertheless concerning that the Department apparently has too few psychologists available to ensure timely reviews of eligibility applications and possibly for other functions.

According to the job postings, those other functions for psychologists include providing services to “individuals in crisis,” “completing functional behavior assessments,” providing clinical consultation and training to DDS service providers, and helping to “enhance newly created behavioral treatment strategies.”

It’s not clear whether the reason for the Department’s lack of clinical resources has to do with the salary range that the Department offers or what the Department may be doing to rectify the situation.

We hope that the next set of documents we are expecting from DDS will shed more light on this issue. What these documents show so far is evidence of what appears to be growing dysfunction within DDS in carrying out its mission of caring for the most vulnerable members of our society.

The burdens of Supported Decision Making will fall primarily on women

Guest post by Lara Dionne

As one of the parent-guardians of a young lady who is 18 years old and has Level 2 autism and moderate intellectual disability, I am very concerned about bills pending in the state Legislature to authorize Supported Decision Making (SDM) in Massachusetts (S.109 and H.201).

SDM would enable persons with developmental disabilities to sign agreements with informal teams of supporters, who would “help” them make decisions about all aspects of their care.

SDM is billed as a voluntary alternative to guardianships of those individuals, who are referred to as the “decision makers” in SDM arrangements. In reality, many proponents of SDM want to eliminate guardianships altogether.

The problem is that decision-making capacity (i.e., legal competency) should be included somewhere in S.109/H.201, and it is not. The bills need to recognize those whose disabilities render them unable to make informed, reasonable decisions in their best interest due to deficits in cognition related to developmental disability, intellectual disability, or a mental health condition which impairs sound judgement.

The legal competency issue is obvious and a blatant oversight. The bills’ proponents can’t have failed to recognize that there are some people for whom the SDM process would be entirely inappropriate. Those individuals need guardians, and in most cases, those guardians are their mothers, sisters, and daughters.

SDM will further destabilize families that are already under stress and take additional agency away from the very people the state is relying on to fill the gaping holes in their disability services infrastructure: primarily women.

SDM is a means to the end that the state appears to be seeking. In most cases, the “decision-maker” will choose the course recommended by his or her SDM “team.” That team is likely to consist of providers and Department of Developmental Services (DDS) personnel, in addition to family members.

As a result, it is likely that few “decision-makers” will choose congregate care facilities, and many may choose the lowest-cost option — their family home. Even now, well over half of adults with autism live with family caregivers, according to the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia’s Center for Autism Research.

In case the obvious needs to be stated: It is still overwhelmingly women who take on the burden of caregiving for the disabled in the family home.

Women comprise just over 80% of stay-at-home parents. The Institute on Aging reports that 75% of all caregivers are women, and that female caregivers may spend as much as 50% more time providing care than men. Further, research completed at Drexel University found that 30% of families with a child with autism had to reduce working hours to care for their child.

Given the first two statistics, what do you suppose the likelihood is that those leaving work to provide care for autistic family members are women? Pretty darn high, I would say.

I would also love to know how many of these disabled individuals are cared for by their grandmothers because the state already burned through their parents with the weaponized incompetence that passes for disability services for this population. However, I suspect this is a set of statistics the state does not want to gather for many reasons.

My concern is that S.109/H.201 is yet another bit of health and human services legislation that claims to give autonomy to one oppressed class of individuals by taking away the autonomy of another oppressed class whose members will be expected to suffer the financial fallout and complete any labor associated with it: women.

It is worth considering the following: Is the state entitled to rely on the free labor primarily of women to fill in their programming gaps while they dismantle state-run services and outsource them to unstable private vendors? Is the state entitled to the free labor of women to care for legal adult citizens? I do not think it is.

When most children grow to adulthood, their parents can then focus on their career and build financial security with the goal of retiring someday. Why does the state think that parents ― again, mostly mothers ― of adult children with disabilities are not entitled to that?

I was shocked to learn that, in Massachusetts, parents and guardians cannot be paid caregivers under most MassHealth programs, including adult foster care and personal care attendant services. There is currently a crisis-level shortage of professional caregivers for our disabled and elderly. Yet Massachusetts will not pay families to do the work.

Massachusetts expects that families work for free, and they are getting it. That doesn’t really give the state much incentive to fix the direct care workforce shortage, does it? They are balancing their budgets on the backs of women.

There is proposed legislation this session — S. 775/H. 1232, An Act Relative to Family Members Serving as Caregivers — to undo this overtly exploitative practice of relying on unpaid, mostly female, caregivers in adult long-term care. The bill would allow legally liable individuals, parents and guardians, to be paid caregivers for their adult children under MassHealth programs.

According to Massachusetts regulation (101 CMR 420.00), which governs reimbursement for Adult Long-term Residential (ALTR) Services, the state pays a group home provider over $200,000 a year on average for adult residential services for an individual with autism and intellectual disability. It would seem humane to allow mothers (or other family members) providing the same care to receive a fraction of that $200,000, equal to a living wage.

To elaborate further on the lack of basic human decency extended to unpaid female caregivers of children with disabilities, employees in a group home setting have their employment governed by U.S. labor laws. Depending on the number of employees in their parent company, they may receive health insurance and family medical leave. They may get work credit toward future social security benefits. Many companies that provide group home services give their employees paid time off and overtime pay.

Most importantly, group home employees are able to go home and rest at the end of a shift, away from the demands of their charges. Mom gets none of those things. Her shift never ends. Where was the Department of Labor when mothers were being written out of these MassHealth caregiving programs? Why is the caregiving labor of family members ― again, primarily women ― not seen as labor while someone else does it for pay?

Women who have children with significant disabilities have often been out of the paid full-time workforce for years by the time their child reaches adulthood. It seems that keeping individuals with disabilities and their caregivers in poverty is an intentional feature of most government programs. The poor have no voice. The poor are too busy surviving to object to the violation of their civil rights. The poor become invisible.

When we closed the doors of many institutions, the level of support needed by disabled individuals with more profound disabilities did not decrease or cease to exist. Yet the state assumes that the mystical powers of motherhood will somehow miraculously accomplish what it used to take teams of paid professionals to do.

I urge you all to find and read the excellent article in The Boston Globe last month on abuse and neglect occurring in residential schools for children with autism and intellectual disability. Some people who are being paid, albeit inadequately, to do this labor are resorting to abusing clients.

When an excuse is offered for such egregious violations, it usually mentions the stresses of the job, staff turnover, and chronic understaffing. Still, these employees do have the supports and protections mentioned earlier.

Yet the burden on family caregivers ― primarily mothers ― is inordinately higher and there is no compensation involved. Mothers are expected to endure all that the inadequately compensated direct care workforce endures, and they are expected to do it alone, or while impoverishing themselves to qualify for any state support for their child.

Why is it not expected that this is going to result in domestic violence and child abuse? That would seem logical given what is happening in the paid disability services workforce. It is that mystical power of motherhood again, isn’t it?

The assumption of the right to the free labor of women doing work they cannot possibly do alone, given the lack of available state resources and, in many cases, the level of their child’s disability, is not only misogynistic, it is ableist. Yet SDM is designed to further support the push toward privatization and reliance on “natural supports” when this system can clearly be seen to be failing those with more profound disabilities.

SDM will place additional labor burdens on female caregivers, as well. The guardianship process is onerous enough, as it should be, given its gravity. However, once guardianship is approved, a legal guardian can provide caregiving services without needing to consult a team of people who may be difficult to assemble. It is hard enough for women to take time away from primary caregiving and a job and household demands to perform necessary legal and financial tasks for their adult children with disabilities.

Many of these tasks involve multiple calls, meetings, paperwork, and errands. For example: Has anyone had to apply for SSI on behalf of their adult child? Acquiring a state I.D. for documentation purposes, applying to be their representative payee (because guardianship isn’t enough to represent them with the Social Security Administration), and opening a representative payee bank account are quite a bit of work. Now imagine doing it in committee.

The adult child is not going to be able to perform this labor themselves. I also tend to doubt that their SDM team is going to do much of this work, if the disabled adult lives with family. It will be Mom or Grandma doing it with everyone on the team getting to tell them how to do their job.

Poor, working, and middle-class women will be unable to buy their way out of the caregiving responsibilities that will continue to be forced on them by SDM. The unpaid labor expectations and the micromanagement by a team of individuals, who will have interests and agendas that conflict with the health of the entire family unit, will push many female caregivers beyond their breaking point.

The state knows this, but the state also knows it has mothers over a barrel. At every stage in the life journey of your disabled child, mothers are expected to make a choice: Choose to sacrifice yourself or choose to potentially sacrifice your child’s health and future.

There is never a choice that considers the inherent worth and civil rights of both individuals. It is never mother AND child in disability law. It is solely focused on the child, but it depends upon ― it assumes the right to enlist― the mother’s labor in a manner that sacrifices her health, her career, and her financial independence.

Disability law creates dependency in female caregivers that leaves them vulnerable to poverty and abuse. It removes their agency. The SDM legislation (S.109/H.201) is merely the latest incarnation of disability law continuing that pattern.

It is morally wrong to rely on the lifelong free labor of a particular class of people — based on their sex — to save money and shirk social responsibility. This assumption of the right to the free labor of women bars many women from equal access to educational advancement, civic involvement, and financial security and independence.

Disempowering women further disempowers adults with profound autism and intellectual disability. Many of these adults cannot advocate for themselves. Women ― mothers ― are their voices. If the mothers of the profoundly disabled have no access to the power structure in our society, their children have no voice within that power structure. Their children’s needs go unanswered.

The desire to be able to earn a living wage, to prepare for a somewhat secure retirement, and to protect our physical and mental health does not mean that we women do not love our children and grandchildren. It means that we are people with rights to be considered too.

You can’t give freedoms to one class of people that rely on the continued oppression of another.

___________________________________________________________________

Lara Dionne is a COFAR member and is currently attending Salem State University, working on a Certificate in Data Analytics, with the long-term goal of getting back into the workforce after many years of caregiving for both her daughter and elderly relatives. She looks forward to being paid for her labors, again.

Lara Dionne is a COFAR member and is currently attending Salem State University, working on a Certificate in Data Analytics, with the long-term goal of getting back into the workforce after many years of caregiving for both her daughter and elderly relatives. She looks forward to being paid for her labors, again.

DDS: We’re ‘not required to answer questions’ about the number of state-run group homes or of residents

As we have reported, the census or number of residents living in state-operated residential group homes and Intermediate Care Facilities (ICFs) in Massachusetts appears to be steadily declining.

But in response to Public Records requests filed by COFAR, first in January and then last month, the Department of Developmental Services (DDS) said it no longer has information on the actual number of people living in state-operated group homes during the past five years.

If it is true that DDS has no such records, it would indicate that the Department is unaware of the status of one of its most important operational programs.

DDS has also declined to clarify an apparent discrepancy in its claims concerning the number of state-operated group homes that have been closed since 2021.

We have appealed to the state’s public records supervisor in an effort to get clarification on those matters. In a response filed on Friday to our appeal, a DDS attorney said that under the Public Records Law, “an agency is not required to answer questions…”

Denial of group home information

Prior to this year, DDS did provide us with information on the declining census in state-operated group homes. That data showed a steady decline from a high of 1,206 residents in Fiscal Year 2015, to 1,097 in 2021. During that same time, the census in the much larger network of corporate, provider run group homes, also funded by DDS, rose from 7,793 to 8,290.

But as of January of this year, as noted, that information on the census in the state-operated group home system is apparently no longer available. What DDS said in January and again in September is that while it can provide information on the total available beds in, or capacity of, state-run group homes over the past five years, it now has no records on the census.

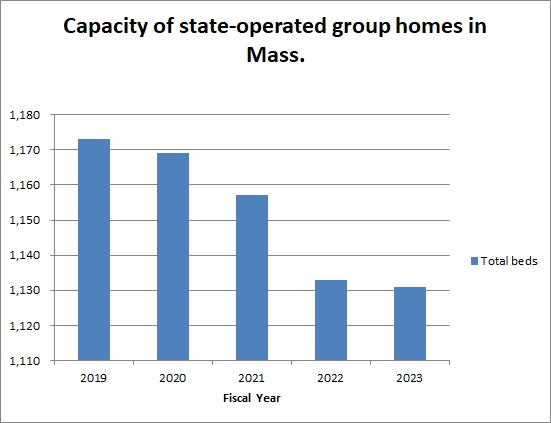

In September, DDS stated that the total capacity of the homes had declined from 1,173 beds to 1,131 beds between Fiscal 2019 and 2023.

But capacity numbers don’t tell the full story, particularly if DDS has not been allowing admissions to the group homes, and there consequently are vacancies in them. In fact, DDS acknowledged last month that there were 91 vacancies in the state-run group home system as of June of this year. That would imply that the actual census in the homes is lower than the capacity.

But DDS also said that while there were 91 vacancies as of June 30, it has no records on the number of vacancies each year since Fiscal Year 2019.

We calculated the apparent drop in the census as of Fiscal Year 2023

Based on the Department’s partial records, we did our own calculation of the census in the state-run group home network as of Fiscal Year 2023. That year, it appears the census would have dropped to 1,040.

That census or number of residents is based on DDS’s statement that the capacity of the state-run group homes was 1,131 in Fiscal 2023, and that there were 91 vacancies in the group homes as of June 30, the last day of that fiscal year. Subtracting the number of vacancies from the census that year equals 1,040. (1,131 minus 91).

If that is the case, it would indicate that the census in the state-run group homes dropped from 1,206 in Fiscal 2015 to 1,040 in Fiscal 2023, a 14% drop. See our chart below.

(Source: DDS. Note: We were not able to calculate the census in the state-run group homes in Fiscal Year 2022 because DDS did not provide a figure on the number of vacancies in that fiscal year.)

(Source: DDS. Note: We were not able to calculate the census in the state-run group homes in Fiscal Year 2022 because DDS did not provide a figure on the number of vacancies in that fiscal year.)

DDS will not clarify number of homes closed

As noted, DDS is not willing to clarify seemingly contradictory information on the number of group homes that have been closed and subsequently reopened since August 2021, during the height of the COVID crisis.

In September, DDS indicated that a net of nine state-run homes were closed between August 2021 and September 2023, leaving 251 homes remaining. However, eight months earlier – in January — DDS indicated that a net of six state-run homes were closed between August 2021 and January 2023, leaving 250 homes remaining as of January.

The implication of the January data was that 256 homes existed as of August 2021, whereas the implication of the September data was that 260 homes existed as of August 2021. The discrepancy might also mean that the number of homes that DDS said were closed may have been inaccurate.

However, as noted, when I asked that DDS provide clarification regarding that apparent discrepancy, a DDS attorney stated that, “Under the PRL (Public Records Law), an agency is not required to answer questions…”

The Public Records Law does require clarity

As part of our appeal, we stated to the public records supervisor that we believe DDS is, in fact, obligated to clarify information it provides under the Public Records Law.

The Massachusetts Guide to the Public Records Law, updated in March 2020, states that, “(State agencies) must help the requestor to determine the precise record or records responsive to a request…”

Also, the Public Records Law [M.G. L. c. 66, § 6A(b)] states that:

(The state agency) shall: …(i) assist persons seeking public records to identify the records sought;… and (iii) prepare guidelines that enable a person seeking access to public records in the custody of the agency or municipality to make informed requests regarding the availability of such public records electronically or otherwise…Each agency and municipality that maintains a website shall post the guidelines on its website.

In asking for clarification regarding the number of homes that existed as of August 2021 and have subsequently been closed, we were seeking the Department’s help in determining the precise record or records that might be responsive to our Public Records requests.

In sum, DDS’s response to our latest records requests seems to be part of the Department’s usual pattern of providing as little information as it feels it can get away with under the Public Records Law. The only other explanation is that the Department doesn’t have basic information about the programs it runs. We’re not sure which explanation is more troubling.

DDS confirms 91 vacancies in state-operated group homes even after several homes are shut

The Department of Developmental Services has confirmed for the first time that there are dozens of vacant beds in its state-operated group home network, even though the Department also says it has closed a net of nine homes since August 2021.

That information was provided to us in response to a Public Records Request, which we filed earlier this month with the Department.

In a response on September 26 to our request, DDS stated that as of June 30, there were 91 vacancies in the state-operated group home system.

COFAR has long contended that there are vacancies in state-operated homes because DDS generally does not inform individuals seeking residential placements of the existence of that system. Instead, DDS seeks to place virtually all persons in its much larger network of corporate provider-run group homes.

We are frequently told by families seeking placements for their loved ones in the state-run system that there are no vacancies in state-operated homes.

DDS also does not inform or generally admit persons to either of its two remaining Intermediate Care Facilities (ICFs) in the state – the Wrentham Developmental Center or the Hogan Regional Center. As a result, the number of residents living in state-run residential facilities has continued to decline, while the number in corporate run group homes has been steadily increasing.

COFAR has periodically filed Public Records requests with DDS to track the declining census in both the state-operated group home system and the Wrentham and Hogan Centers. The Wrentham and Hogan centers are the last remaining, congregate ICFs in the state.

DDS has continued to maintain that the corporate provider system is less restrictive and better integrated into the community than is the state-run residential system. However, as a Spotlight investigation by The Boston Globe showed on September 27, the corporate group home system is beset by abuse and neglect.

The data provided by DDS on September 26 show the following:

- There were 91 empty beds in state-operated group homes as of June 30. The Department, however, said it “does not have any responsive records” pertaining to COFAR’s request for the number of vacancies in the state-operated group homes each year from Fiscal Year 2019 to the present.

- The census, or total number of residents, at the Wrentham Center dropped by 48%, from 323 residents in Fiscal 2013, to 167 in Fiscal 2023.

- The census at Hogan dropped from 159 in Fiscal 2011, to 95 in Fiscal 2023, a 40% drop.

- The total census in the state-run group home system dropped by nearly 10% between Fiscal 2015 and 2021, according to previous DDS data. However, DDS has not provided information on the census in the state-run homes since 2021. We have appealed that apparent information denial to the state supervisor of public records.

- The total capacity, or number of beds, in the state-run group home system declined by 3.6% from Fiscal Year 2019 to Fiscal 2023.

- DDS says it closed a net of nine state-operated homes between August 2021 and September of this year. As noted below, the numbers don’t appear to add up, however. We’ve appealed for clarification.

Declining capacity and census in state-operated group homes

As the chart we created below based on the DDS data shows, the total capacity or number of beds has continued to decline in state-run group homes. That capacity declined from 1,173 beds to 1,131 beds, or by 3.6%, between Fiscal 2019 and 2023.

Previous data from DDS showed that the total census in the state-operated group homes declined from a high of 1,206 in Fiscal 2015, to 1,097 in 2021 — a 9% drop.

DDS numbers don’t add up

In addition to appealing the lack of census information regarding the state-run group home system subsequent to 2021, we are appealing to the public records supervisor to seek clarification from DDS regarding an apparent discrepancy in the numbers the Department has given of homes that have been closed since 2021.

The September 2023 DDS response to our Public Records request indicated that a net of 9 state-run homes were closed between August 2021 and September 2023, leaving 251 homes remaining.

However, data previously provided in January indicated that a net of 6 state-run homes were closed between August 2021 and January 2023, leaving 250 homes remaining as of January.

The implication of the January data was that 256 homes existed as of August 2021, whereas the implication of the September data was that 260 homes existed as of August 2021.

We have asked the public records supervisor to require DDS to account for the apparent difference between the two responses in the number of homes that existed as of August 2021.

DDS consistently maintains it has no records regarding the future of state-operated care

Despite the continuing downward trend in the census at Wrentham and Hogan, DDS said in January and again in September that they have no records concerning projections of the future census of those facilities or concerning plans to close them. Nevertheless, we maintain that unless DDS opens the doors at those settings to new residents, they will eventually close.

Violation of federal law not to offer state-run facilities

In a June 5 legal brief, DDS argued that federal law does not give persons with intellectual or developmental disabilities the right to placement at either the Wrentham or Hogan Centers. We think the Department’s argument in the brief misrepresents federal law, and reflects an unfounded bias among policy makers in Massachusetts against ICFs.

As Medicaid.gov, the federal government’s official Medicaid website, explains, “States may not limit access to ICF/IID service, or make it subject to waiting lists, as they may for Home and Community Based Services (HCBS)” (my emphasis). In our view, the federal Medicaid law and its regulations confer the right to the choice of ICF care to individuals and their families and guardians.

Meetings with state and federal lawmakers to bring these concerns to their attention

Last week, we met online with state Representative Jay Livingstone, the new House chair of the state Legislature’s Children, Families, and Persons with Disabilities Committee, to raise our concern about the declining census in state-run facilities and to discuss their vital contribution to adequate care in the system. We are similarly seeking a meeting with Senator Robyn Kennedy, the new Senate chair of the committee.

So far, we have also met online with legislative staffs of U.S. Senators Elizabeth Warren and Ed Markey, and of U.S. Representatives James McGovern, Lori Trahan, Catherine Clark, Seth Moulton, and Stephen Lynch, and have imparted that message. We still have four additional members to meet with in the Massachusetts congressional delegation.

In our meetings with the staff members of the congressional delegation, we are urging that the lawmakers oppose pending bills that would expand funding to the largely privatized, community-based system, but would not direct similar funding to either Wrentham or Hogan.

In sum, the data we have gotten from DDS have shown a consistent pattern by multiple administrations of building up the privatized DDS group home system while letting state-run residential facilities wither and ultimately die. As we’ve said before, we think that will result in a race to the bottom in the quality of care in the DDS system.

In our experience, state-run residential facilities in Massachusetts, as in most other states, meet higher standards for care than do privatized settings, and tend to have higher paid, better trained, and more caring staff. We want to bring that message to our state and federal legislators before it’s too late.

Latest Supported Decision Making bill offers no improvements over previous versions

We first pointed out problems seven years ago with a bill in the state Legislature that would authorize Supported Decision Making (SDM) in Massachusetts.

SDM involves written agreements to replace guardians of persons with developmental disabilities with informal teams of “supporters” or advisors.

Each year, SDM legislation has gotten closer and closer to final passage in the Legislature; and yet, as far as we can see, the proponents of the bill have not made what we argue are needed changes or improvements to the versions of the bill that they have continued to file.

This year’s version of the bill, S. 109, is no exception. In our view, it has the same problems as the previous versions.

Last year’s version of the bill (S. 3132) passed the Senate in November and died in the House Ways and Means Committee, just one step away from final passage in the full House. At the time, we had urged the Ways and Means Committee not to send the bill to the House for final passage.

As we noted in a previous post about that bill, it lacked provisions to protect the rights of persons with intellectual and developmental disabilities, and their families and guardians.

S.109, this year’s version, is now before the Children, Families, and Persons with Disabilities Committee. We are similarly asking the Committee this year not to advance the bill in the legislative process without making needed changes to it.

Under the bill, an SDM “supporter” or “supporters” would help an individual with an intellectual disability, known as the “decision-maker,” make key life decisions, including decisions about their care and finances. Most people with developmental disabilities currently have guardians, most of whom are family members of those individuals. But SDM proponents maintain that guardianship, even when guardians are family members, unduly restricts an individual’s right to make those decisions.

But persons with severe and profound levels of intellectual disability have greatly diminished decision-making capacities. We think many of those people are likely to be vulnerable to coercion and financial exploitation from persons on their SDM teams who may “help” them make financial decisions that don’t reflect their wishes.

In these situations, family members of persons with developmental disabilities, whom we have found to be likely to act in the best interest of their loved ones, may find themselves outvoted on the support teams by other team members who may stand to benefit financially from the clients’ “decisions.”

Legislation still does not provide a standard for judging the decision-making capacity of the individual

In our view, a key piece missing from the SDM legislation so far has been a standard for the level of intellectual disability above which an individual can reasonably be considered to be capable of making decisions with “support” from clinicians, paid caregivers, and other SDM team members.

As was the case with previous versions of the bill, S.109 defines the “decision-maker” as “an adult who seeks to execute, or has executed, a supported decision making agreement with one or more supporters…”

There is no further specification about the decision maker in the bill. There is no differentiation in the definition between individuals with greater or lesser degrees of intellectual disability, and no consideration whether persons with low levels of cognitive functioning are really capable of making and appreciating life-altering decisions.

As a 2013 article on SDM in the Penn State Law Review stated,

…there is a potentially unavoidable paradox in acknowledging that a person has diminished decision-making capacity but maintaining that he or she is nevertheless capable of meaningfully contributing to decision-making discussions and that the decisions that result from such discussions reflect his or her wishes. (my emphasis)

Also, “Supported decision-making” is defined in S.109 as:

…the process of supporting and accommodating the decision-maker, without impeding the self-determination of the decision-maker, in making life decisions, including, but not limited to: (i) decisions related to where the decision-maker wants to live; (ii) the services, supports, financial decisions and medical care the decision-maker wants to receive; (iii) whom the decision-maker wants to live with; and (iv) where the decision-maker wants to work.

There is no specification as to whether the “supporter(s)” would be family members. In other words, family members could be frozen out of the decision-making process if they were consistently outvoted by other supporters.

Bill doesn’t require court approval of an SDM arrangement

Currently, a person applying for guardianship must state in probate court the reason why a guardianship is necessary; and if they are applying for a full guardianship, the reason why a limited guardianship is inappropriate.

There is no requirement in S. 109, however, that the probate court approve an application for an SDM arrangement. However, S.109 would impose an additional burden in probate court on family members who continue to seek guardianship of their loved ones.

Under S. 109, an applicant for guardianship would now have to state in court, “whether alternatives to guardianship … including a supported decision-making agreement, were considered, (and) why such alternatives to guardianship and supports and services are not feasible or would not prevent the need for guardianship” (my emphasis).

Given that applying for guardianship requires probate court approval, it isn’t clear to us why that shouldn’t also be the case with an SDM agreement, which would entail making the same types of life decisions involving an incapacitated individual. Moreover, it isn’t clear why applicants for guardianships should have an additional burden placed on them in court to show why an SDM arrangement, rather than the requested guardianship, isn’t needed.

No clear protection against financial or other exploitation

S.109 states that, “Evidence of undue influence or coercion in the creation or signing of a supported decision-making agreement shall render the supported decision-making agreement invalid.”

This statement in the bill appears to recognize the possibility that a developmentally disabled individual can be influenced or coerced into signing a SDM agreement. The problem with the bill in this regard is there is no description of the type or level of coercion that would invalidate an SDM agreement. Also, the bill doesn’t specify who would invalidate the agreement in that case.

The legislation states that if a person suspects that a disabled individual is being abused or exploited under an SDM arrangement, they can take their complaint to the Disabled Persons Protection Commission (DPPC). But while the DPPC’s enabling statute authorizes the agency to investigate allegations of abuse and neglect, the DPPC is not specifically charged with investigating cases of alleged coercion in signing agreements.

S. 109 also states that the DPPC and the Department of Developmental Services (DDS) may petition the probate court to revoke or suspend a SDM agreement on the grounds of abuse, neglect or exploitation by supporters. But the bill doesn’t say that either the DPPC or DDS will or must petition the court to revoke the SDM agreement even if they do find abuse or neglect. It says only that they “may” petition the court to do so.

No protection against conflicts of interest, and no funding

Members of an individual’s SDM team who are also service providers to that person face a potential conflict of interest when they advise the “decision maker” about making use of the services they provide.

A Syracuse Law Review article published last year about SDM pilot projects in Massachusetts identified, or at least implied, a number of problems or difficulties associated with SDM, including conflicts of interest involving providers.

The Syracuse Law Review article stated that in the Massachusetts pilot project:

…project staff had frank discussions with the Decision Maker and supporters about any potential conflict of interest and how to draft an agreement to minimize the potential conflict, such as having paid supporters not assist with decision-making support for issues that concern services from the agency paying the supporter (my emphasis).

But like bills that have come before it, S.109 does not require any separation between provider employees and individuals on the SDM team. They can serve in both capacities.

The Syracuse Law Review article also stated that one of the lessons of the Massachusetts and other pilot projects was that “without dedicated funding, ample cash reserves or an extraordinary commitment to Supported Decision Making, it is very difficult for organizations to introduce, implement and help to support Supported Decision Making for a large number of individuals.”

There is no reference in S.109, however, to a potential funding mechanism for SDM in Massachusetts.

No dispute resolution process

The Syracuse Law Review article also recognizes that there are likely to be disputes within SDM networks or teams, and noted that a pilot program in New York State created a “Mediation Module designed as a two-day training for mediators.”

While S.109 and previous versions of the bill would require the Executive Office of Health and Human Services in Massachusetts to establish an SDM training program, none of the bills specify or specified either a dispute resolution process for SDM arrangements or training in dispute resolution.

Families may not fully understand the guardianship rights they will be forgoing

SDM advocates argue that the process is entirely voluntary on the part of the intellectually disabled individual, and that family members can still opt to go to court to apply for guardianship.

But it may be wrong in all cases to assume that someone who has a severe or profound level of intellectual disability has not been coerced into making what may look on the surface like a voluntary decision. Also, while a family member may still go to court to become a guardian, the SDM legislation, as noted, would increase the burden on them to make the case for guardianship.

And while family members might be persuaded to willingly enter into SDM agreements rather than to seek guardianship of their loved ones, we think many family members may not realize the amount of authority they would be ceding in doing so. Under an SDM arrangement, a family member would become just one member of the SDM team.

It has been our experience, that in many disputes over care, family members find themselves pitted against a united front of provider and DDS personnel. This would seem to be a highly likely dynamic in an SDM arrangement.

Unless and until the proponents of this legislation finally agree to address these issues and improve the bill, we can’t support it.

Why we are asking federal and state lawmakers to help save the Wrentham and Hogan Intermediate Care Facilities

We believe individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities in Massachusetts have a right under federal law to care at the Wrentham and Hogan Intermediate Care Facilities (ICFs).

They also have a right to work opportunities in their day programs and other congregate care settings.

Those rights are under continued assault. (See here and here.)

As a result, we are contacting members of the Massachusetts delegation in Congress and key members of the state Legislature, and are asking them to relay information about those rights to policymakers at the federal and state levels.

It seems to us that most lawmakers and policymakers do not recognize the wide range of functioning and needs among people with intellectual and developmental disabilities, or the importance of giving this population a full continuum of choice. One size does not fit all.

DDS phasing out state-run residential care

The Massachusetts Department of Developmental Services (DDS) is allowing the state’s two remaining ICFs — the Wrentham Developmental Center and the Hogan Regional Center — to slowly die by attrition. We believe the eventual closures of these essential backstops for care of the state’s most profoundly disabled residents will be disastrous.

So far, we have met online with legislative staff of U.S. Senators Elizabeth Warren and Ed Markey, and of Representatives James McGovern, Seth Moulton, and Catherine Clark, and imparted that message. We still have six additional members to meet with in the congressional delegation.

Next week, we will also meet online with staff of state Senator Robyn Kennedy, the new Senate chair of the Legislature’s Children, Families, and Persons with Disabilities Committee. We hope to discuss these issues with Senator Kennedy herself, at some point, and will try to schedule a meeting soon with state Representative Jay Livingstone, House chair of the Committee, and his staff.

We want these legislators to know that DDS has failed to inform families and guardians of individuals in the DDS system of the existence of the Wrentham and Hogan Centers, and, with few exceptions, has denied their requests to place their loved ones in those facilities. The Department is also failing to inform people of the existence of its network of state-operated group homes.

What DDS has done has been to attempt to place virtually all persons waiting for residential services in the much larger network of corporate provider-run group homes that the Department funds.

That policy was explicitly confirmed in a decision earlier this month in which DDS Commissioner Jane Ryder upheld the denial of an appeal by the parents of an intellectually disabled man to place their son at Wrentham.

In that case, the parents presented evidence that their son has received inadequate services in his provider-run group home. He is also facing eviction from the residence, and had been abused by staff employed by his group home and day program provider. But a DDS-appointed hearing officer adopted the Department’s position that “federal law does not entitle the (son) to admission to an Intermediate Care Facility at WDC (the Wrentham Center).”

DDS policy runs counter to federal rules

As Medicaid.gov, the federal government’s official Medicaid website, explains, “States may not limit access to ICF/IID service, or make it subject to waiting lists, as they may for Home and Community Based Services (HCBS)” (my emphasis). The son’s group home in the appeal case is run by a corporate DDS provider that is partly federally funded under the HCBS program.

Unfortunately, in his decision, the hearing officer confirmed that DDS’s policy is the opposite of the federally prescribed policy that states may not limit access to ICFs. The hearing officer stated that he agreed with the testimony of a DDS regional director in the appeal hearing that, “DDS avoids institutionalization at the ICFs except in cases where there is a health or safety risk to the individual or others, and generally, when all other community-based options have been exhausted.”

In our view, however, the federal Medicaid law and its regulations confer the right to the choice of ICF care to individuals and their families and guardians.

DDS, like many advocates of deinstitutionalization of care for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities, has also regularly misinterpreted the landmark Olmstead v. L.C. Supreme Court decision, which also implies a right to ICF care for those who desire it.

Federal ICF legislation that we support and oppose

In our meetings, we are urging lawmakers in Congress to oppose pending bills that would expand funding to largely privatized HCBS system, but would not direct similar funding to ICFs.

We oppose:

The Latonya Reeves Freedom Act of 2023

- H.R. 2708 (Steve Cohen, D-TN) https://www.congress.gov/bill/118th-congress/house-bill/2708

- S.1193 (Michael Bennett, D-CO) https://www.congress.gov/bill/118th-congress/senate-bill/1193

As Hugo Dwyer, executive director of the VOR, our national affiliate explained, this legislation was proposed by ADAPT, an organization that has “repeatedly called for the elimination of the ICF model.” Dwyer stated that VOR supports “keeping all services available and allowing individuals and their families to choose what is right for them.”

- H.R.547 (Debbie Dingell, D-MI) https://www.congress.gov/bill/118th-congress/house-bill/547

- S.100 (Bob Casey, D-PA) https://www.congress.gov/bill/118th-congress/senate-bill/100

- H.R.1493 (Debbie Dingell, D-MI) https://www.congress.gov/bill/118th-congress/house-bill/1493

- S.762 (Bob Casey, D-PA) https://www.congress.gov/bill/118th-congress/senate-bill/762

Dwyer noted that these latter bills would increase federal Medicaid funding for direct-care wages, which we and VOR support. But those wage increases would be in HCBS settings only, leaving out the ICFs.

We support:

Recognizing the Role of Direct Support Professionals Act

- H.R.2941 (Brian Fitzpatrick, R-PA) https://www.congress.gov/bill/118th-congress/house-bill/2941

- S. 1332 (Maggie Hassan, D-NH) https://www.congress.gov/bill/118th-congress/senate-bill/1332

Dwyer said these bills would help raise wages and training of direct-care staff in all settings, including ICFs.

Work opportunities legislation

With regard to work opportunities for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities, two pending bills in Congress would encourage such opportunities:

We support:

- H.R.1296 (Glenn Grothman, R-WI) https://www.congress.gov/bill/118th-congress/house-bill/1296

- H.R.553 (Glenn Grothman, R-WI) https://www.congress.gov/bill/118th-congress/house-bill/553

The Restoration of Employment Act would give an individual a choice whether to accept employment at a subminimum wage. (This blog post explains why the subminimum wage is needed by people who are unable to compete in the mainstream workforce.)

The Workplace Choice Act states that a program setting in which an intellectually disabled individual is able to interact with “colleagues, vendors, customers, and superiors…” would be considered a “competitive, integrated employment” setting. This would allow people who can’t compete in the mainstream workforce to be provided with work activities in their day programs.

We oppose:

- H.R. 1263 (Bobby Scott, D-VA) https://www.congress.gov/bill/118th-congress/house-bill/1263

- S.533 (Bob Casey, D-PA) https://www.congress.gov/bill/118th-congress/senate-bill/533

- H.R. 4889 (Bobby Scott, D-VA) https://www.congress.gov/bill/118th-congress/house-bill/4889

- S.2488 (Bernie Sanders, I-VT) https://www.congress.gov/bill/118th-congress/senate-bill/2488

The legislation above would make work opportunities harder to find for people who can’t handle mainstream work environments. Those bills would remove the option of the subminimum wage.

A number of family members have joined us in our online meetings with legislators. If you are interested in attending upcoming meetings, let us know. Your stories are vitally important for lawmakers and policymakers to know.

In ruling criticized as biased, DDS denies family’s request to place son at the Wrentham Center

As had been expected, Department of Developmental Services (DDS) Commissioner Jane Ryder last week upheld the denial of a request by a couple to place their intellectually disabled son at the Wrentham Developmental Center.

Ryder upheld a recommended decision by DDS Hearing Officer William O’Connell, who had previously denied a request by the couple to submit a COFAR blog post in rebuttal to a DDS closing brief in the case.

The COFAR post claims, among other things, that federal law gives individuals a right to care in an Intermediate Care Facility (ICF) such as the Wrentham Center.

The couple, who have asked that their names not be used, have sought the Wrentham placement as part of an appeal of their son’s Individual Support Plan (ISP). They contend the DDS-funded corporate provider that operates their son’s group home and day habilitation program does not provide services their son needs, such as nursing, speech and occupational therapy; and they note that these services are provided at Wrentham.

O’Connell’s 24-page recommended decision denying the couple’s appeal was dated July 20. The couple maintain that the language and reasoning in O’Connell’s decision confirms that he held a bias against them and in favor of DDS.

Son had been abused at day hab program and is facing eviction from group home

The couple also stated in their appeal that their son had been sexually and physically abused in his day hab facility. They further stated that the provider sought last September to evict their son from the group home after he had a toileting accident on the group home’s outside deck.

The eviction is currently on hold based on the couple’s objection to it under DDS regulations.

The couple said they are considering an appeal of O’Connell’s decision in state Superior Court. They said their hope is that a win in court would establish a precedent for other families seeking to place their loved ones with intellectual and developmental disabilities at either Wrentham or the Hogan Regional Center, the two remaining congregate ICFs in Massachusetts.

In ruling against the couple, O’Connell cited the testimony of two DDS regional directors during a hearing on the couple’s appeal in April. O’Connell stated that based on that testimony, he concluded that “the assessments and/or goals used to develop (the son’s) ISP…form a more than adequate basis for service planning for (the son), including his needs and treatments.”

O’Connell also stated in his decision that the son’s current services are “the ‘least restrictive’ to meet (his) current needs.”

O’Connell’s decision, however, largely did not address the couple’s contention that the actual services their son has received in his group home are inadequate.

Also, as COFAR pointed out in the blog post, which O’Connell would not allow to be submitted, “a statement that a community-based setting is necessarily less restrictive than an ICF is an ideological position that ignores the evidence.”

Hearing officer appeared to have a bias against the family

The couple further noted to us that the regional directors whose testimony was cited by O’Connell are bureaucrats who are largely unfamiliar with the day-to-day care of the son. Yet, the couple said, O’Connell clearly placed all of his credence in the directors’ testimony and not in their own testimony.

In his final decision, O’Connell used the term “credible” or “credibly” to describe the testimony of the two DDS regional directors at least 14 times, while repeatedly stating that the couple had “not met the burden of proof” and had not provided “probative evidence” to support their request that their son be placed at Wrentham. He didn’t explain why their evidence wasn’t probative.

The mother also told us that during the April hearing, O’Connell had expressed repeated impatience with her, telling her to “get to the point…” She said he never interrupted the DDS attorney.

O’Connell had also stated in his previous ruling that the COFAR Blog post was “not probative” as a reason for refusing to consider COFAR’s rebuttal to the DDS closing brief. The blog post would have required him to address several points including:

- That the federal Medicaid statute does provide a right and choice to individuals and their families to ICF care.

- That care at Wrentham and Hogan is not necessarily more restrictive than in provider-run group homes.

- That the couple’s son’s care in the community-based system has not been successful for the past 13 years, as the DDS closing brief stated, and O’Connell repeated.

- That DDS’s policy for many years of blocking new admissions to both Wrentham and Hogan is likely to result in the eventual closure of both of these vitally important backstops of care for some of the state’s most vulnerable residents.

In his decision, O’Connell also repeatedly stated that the couple had rejected all providers of community-based residential services that DDS had identified for them. But he did not acknowledge that the couple said they did so because they believe the community-based system has failed their son and will continue to do so.

ISP hearing process inherently unfair

COFAR has additionally questioned the fairness of the ISP appeal process, under which both the hearing officer is appointed by the DDS commissioner, and the commissioner then makes the final decision whether to uphold the hearing officer’s ruling. COFAR has called for such appeals to be decided by the state’s independent Division of Administrative Law Appeals.

Hearing officer discounted the impact of sexual and physical abuse of couple’s son

In his decision, O’Connell played down the impact of two incidents of sexual and physical abuse of the couple’s son, which the couple said were part of the reason they don’t believe the community-based system is safe or adequate for him. Both incidents had occurred in the bathroom of the day hab facility.

In one case in 2017, a staff member at the day hab program slapped the son on the head, punched him in the back, grabbed his genitals, and was verbally abusive to him over the course of several days.

In a second case in 2015, the son arrived from the day hab facility with a belt tightened so tightly that the parents couldn’t get it off. They said the belt was used to keep their son from going to the bathroom and moving his bowels. Their son has Crohn’s disease and needs to use the bathroom frequently.

According to the couple, their son cried and screamed when they tried to get the belt off. They said he had clear marks and indentations on his stomach which they photographed. In both cases, abuse was substantiated by the DDS investigations unit.

But O’Connell stated in his decision that:

I credit the (couple’s) concerns regarding (their son’s) well-being and safety given these terrible events, but find they were at day supports, not a residential placement, and thus do not have particular probative effect to the (couple’s) current appeal of the ISP and POC (Plan of Care).

O’Connell also stated, in line with the DDS closing brief, that the abuse happened five or more years ago.

But O’Connell didn’t mention that the same provider that runs the son’s day hab program also runs his group home. Also, there was no evidence presented by DDS or the hearing officer that abuse and neglect in the DDS provider system has become less prevalent in the past five years or that the abuse is unlikely to occur again.

Also, abuse in the provider system in general is not restricted to day programs, but occurs in residential settings. If the son were to be admitted to Wrentham, he would attend a day program there, where the abuse rate is likely to be lower than in the provider system.

We have found that abuse overall is lower in the ICFs than in provider run group homes.

Did not address specific services allegedly missing from the community

In a brief that they filed with their original appeal, the couple stated that there is no speech, occupational, recreational, or vocational therapy available to their son in his group home. The group home provider doesn’t provide those services, but Wrentham does.

The couple also stated that their son’s group home and day hab provider have not assigned a nurse to him or provided the name of a nurse to call in case a medical issue arises. They also said there is no nursing listed on his ISP or day hab service plan.

Also, the couple stated that no one at the group home “knows about (their son’s) health status at any given time.” For instance, they said, no member of the staff was aware their son was due for a colonoscopy in June.

The couple also maintained that in most doctors’ offices in the community, there are no accommodations for individuals like their son who have trouble waiting for long periods of time to be seen by the doctor.

O’Connell’s decision largely did not address these specific issues. However, O’Connell did respond to the couple’s contention that their son is not receiving the proper nursing care, writing that “DDS has indicated they will work with (the provider) and any subsequent residential agency to support (the son’s) specific nursing needs.”

The couple maintained to us, however, that saying DDS will “work with” the provider is a tacit admission that the service doesn’t currently exist, and is not an assurance that anything concrete will be done. Those nursing services, however, do exist at Wrentham.

O’Connell also stated that one of the DDS regional directors “credibly testified” that the couple had stated during an informal conference prior to the hearing that the son’s doctor is “excellent.” While that may be the case, the fact remains that the medical staff at Wrentham are highly trained to deal with people with intellectual disabilities, while medical staff in the community are not.

Also, O’Connell stated that the son’s difficulties in waiting at doctors’ officers “are common and easily managed by staff.” The parents disputed this, saying that if that behavior were easily managed, the problem would have been solved long ago.

Couple says son did not face discharge due to their actions

In his decision, O’Connell, once again adopting the DDS closing brief position, stated that the couple were notified last September that the son’s provider “was looking to discharge (him) from their residential placement services due to the (couple’s) actions, not due to any issue with (the son) or (the provider’s) ability to serve (the son).”

O’Connell did not say what those actions were that the parents allegedly committed. Moreover, the couple disputed O’Connell’s characterization of the matter. According to the couple’s original appeal brief, the incident that led to the discharge notice started when no staff were available in the residence to let their son inside to use the toilet.

The group home blamed the couple following the son’s accident on the group home deck, claiming they failed to clean up the area and failed to notify the staff about it. The couple dispute that charge, saying they used a sheet in their car to clean up the area and then emailed both provider and DDS officials about it.

The couple said there was one other incident that precipitated the discharge notice having to do with a Facebook post that the mother made that was critical of the staff of the group home. Neither of these incidents, in our view, are sufficient reasons to have issued a notice to evict the son. No details were provided in the hearing officer’s decision about either of those reasons for the discharge notice.

In sum, O’Connell’s decision in this case, in our view, shows exactly why the ISP appeal process is inherently unfair to families and guardians. His decision was entirely supportive of DDS’s position, and was entirely dismissive of the testimony and evidence put forth by the parents.

For the reasons the couple enumerated, we too hope they will win in court should they decide to appeal, and that this case would then set a precedent that might serve to save the Wrentham and Hogan Centers and other state-run residential programs and services from eventual extinction.

DDS finally agrees to allow client to stay with shared-living caregiver; but caregiver’s payment will be cut almost 50%

A year after having disenrolled Mercy Mezzanotti from her shared-living program, the Department of Developmental Services (DDS) finally agreed this past spring to allow Mercy to continue to receive shared-living services from her longtime caregiver, Karen Faiola.

But before doing so, the Department’s Worcester area office reassessed Mercy as a candidate for shared-living services, and increased her assessed level of functioning. That move, according to Karen, will cut her previous income for caring for Mercy by close to 50%.

A higher level of functioning implies a lower level of needed services. However, both Karen and Mercy contend that Mercy’s needs and level of functioning have not changed. Mercy was found by DDS in 2004 to qualify to receive Home and Community Based (HCBS) as well as institutional services from DDS.

“They are continuing to punish us,” said Karen, referring to the DDS area office. Karen and Mercy claim both DDS and Venture Community Services, Karen’s former shared-living contract agency, retaliated against them after they alleged that Venture employees abused Mercy emotionally last year.

As we argue below, it also appears that the DDS reassessment of Mercy did not comply with departmental regulations. The regulations require that such an assessment be done by a qualified eligibility team and that notice of the reassessment be provided to Mercy.

Income for caring for Mercy would decline from $38,000 a year to $20,000

Karen said she was told last month by Mercy’s new shared-living contract agency that as a result of the new assessment by DDS, her previous annual income for caring for Mercy will be reduced from $34,000, which she had earned under the Venture contract, to roughly $20,000. Also, she will no longer receive a $4,000 respite allocation for providing services.

Both Karen and Mercy contend the DDS Area Office has deliberately sought to reduce Karen’s pay as part of a continuing vendetta against them for having complained last year that two employees of Venture had emotionally abused Mercy. Karen said the pay cut will it very difficult for her to continue to care for Mercy and to survive financially.

Contract termination followed by involuntary removal from home and disenrollment from program

Mercy has been living in Karen’s Sutton home for the past five years. Karen had been Mercy’s paid shared-living caregiver from 2018 until Venture terminated its contract with Karen in May 2022 without providing a stated reason for the termination. DDS pays corporate providers such as Venture to contract directly with shared-living caregivers.

Prior to the contract termination, Mercy and Karen had complained to Venture that a Venture job coach and a second Venture employee had emotionally abused Mercy.

On the same day that Venture terminated its contract with Karen, a Venture employee removed Mercy against her will from Karen’s home and placed her with another caregiver in Worcester whom Mercy had never met.

When Karen, at Mercy’s insistence, brought Mercy back to her home two days later, DDS moved to disenroll Mercy from its federally reimbursed HCBS program. DDS argued that in leaving the stranger’s home, Mercy was refusing DDS services.

Meanwhile, both Karen and Mercy’s therapist filed complaints with the Disabled Persons Protection Commission (DPPC) of abuse of Mercy by Venture. However, a subsequent review by DDS did not result in any findings concerning those charges, indicating that the charges were not investigated.

In July 2022, Mercy appealed her disenrollment to DDS. In February of this year, a DDS-appointed hearing officer upheld the disenrollment, but left the door open for Mercy to “work with” the DDS area office to reapply for shared-living services.

Melanie Cruz, Mercy’s service coordinator supervisor in the DDS Worcester area office, subsequently told Mercy she would refer her to a new shared-living contract agency. But Cruz then texted Mercy in March to say she would have to undergo an eligibility “reprioritization” before she could be “considered for residential services.”

By that time, Mercy had been without a shared living program for more than a year after Venture’s termination of Karen’s contract. Mercy has nevertheless continued to live with Karen, who continued to provide shared-living services to her without financial compensation.

DDS regulations appear to have been violated: No eligibility team and no notice

DDS regulations (115 CMR 6.02(3)) require that eligibility for DDS services be determined by “regional eligibility teams,” each of which must be comprised of a licensed doctoral level psychologist, a social worker with a master’s degree, and a “Department eligibility specialist.”

Karen said the eligibility reassessment of Mercy was carried out in April by Cruz, the service coordinator supervisor, who is employed by the Area Office. In an email I sent on Tuesday to DDS Commissioner Jane Ryder, I stated that having Cruz undertake the reassessment, on its face, does not appear to comply with the regulations.

In addition, the regulations (115 CMR 6.03 and 6.08) state that after completion of an eligibility determination or redetermination, the regional eligibility team must notify the individual of the determination and their right to appeal within 30 days after receiving the notice.

However, Karen said that as of today (August 4) Mercy still had not received a notice of the reassessment. On Tuesday, Mercy texted Cruz, asking for a copy of the reassessment. But Mercy has not received a response from her, Karen said.

Cruz had previously testified against Mercy

In questioning Cruz’s rationale for reassessing Mercy’s level of functioning, Karen also noted that Cruz had previously testified in favor of Mercy’s disenrollment in a November 2022 DDS hearing on Mercy’s appeal. Karen said she believes Cruz was therefore facing a conflict of interest in subsequently reassessing Mercy for shared-living services.

Reassessment reportedly states that Mercy was without services for the past year

Karen was informed that one of the reasons cited by Cruz for the increase in Mercy’s level of functioning was that Mercy was living “unsupported for the past year.” If that statement is actually contained in Cruz’s reassessment, it is untrue. Karen, in fact, continued to support Mercy over the past year. The only difference between that period and the period prior to it is that Karen was not paid over the past year for caring for Mercy.

It appears that the DDS area office has mishandled this case from the start and has carried out what appears to be a vendetta against Mercy and Karen for having reported the alleged abuse against Mercy.

At the very least, we think, a properly constituted regional eligibility team that is independent of the DDS Worcester area office should assess Mercy’s functional level for shared-living services. DDS should then approve a realistic payment schedule to Karen for providing those services.

DDS hearing officer won’t allow COFAR blog post to be submitted as evidence in couple’s effort to place son at the Wrentham Center

A Department of Developmental Services (DDS) hearing officer has denied a couple’s request to submit a COFAR blog post to him for consideration as part of their appeal to place their son at the Wrentham Developmental Center.

The June 15 COFAR post claims, among other things, that federal law requires DDS to give individuals a choice of care in a facility such as the Wrentham Center. DDS primarily informs people looking for residential settings only of the existence of corporate provider-run group homes.