Archive

Volunteer advocates meet with state senators’ staffs in start of effort to preserve Wrentham and Hogan centers

The fight to preserve the Wrentham and Hogan care centers in Massachusetts began this past Friday with a visit to the State House of a dozen advocates and family members of persons with intellectual and developmental disabilities.

Our group, which included several COFAR members, held meetings with legislative aides to State Senators Paul Feeney and Rebecca Rausch. Rausch’s district includes the Wrentham Developmental Center.

Jim Durkin, legislative director for AFSCME Council 93, a state-employee union in Boston, spoke to us prior to the Friday meetings, noting that AFSCME is currently deeply involved in fighting to save the Pappas Rehabilitation Hospital.

“AFSCME is fully behind your efforts to preserve Wrentham and Hogan, which are vital to the fabric of care in this state,” Durkin said. “Right now, we are fighting the battle for the Pappas Hospital, but we will be working with you to make sure that the ICFs are protected as well.”

The Healey administration’s move to close Pappas and allow Wrentham and Hogan to die by attrition are all part of the same effort to eliminate state-run care under what we have long argued is a faulty assumption that it will save the state money.

The first meeting we had on Friday was with Shane Correale, legislative director for Senator Feeney. We have asked Feeney to draft legislation that would open the doors at Wrentham and Hogan to new admissions and establish housing on the campuses of the facilities for elderly family members of the residents.

Wrentham and Hogan advocates at the State House — (Left to right) Mitchell Sikora (COFAR Board member), Marsha Hunt, Shiri Ronen-Attia, Laurie Noland, Ilene Tanzman, Ana Paula Meehan, Allan Tanzman, Mary Dias, Elaine Strug, Jim Durkin (AFSCME Council 93), and Kim Meehan. (Photo by David Kassel)

During that meeting, COFAR member Irene Tanzman stressed the importance of Intermediate Care Facility (ICF) settings, such as Wrentham and Hogan, which meet federal standards that are stricter than the state standards for group homes. “Not everyone thrives in the community,” Tanzman said, adding that the state is “denying us the opportunity” for ICF-level care.

“We want choice,” Tanzman added. “The community is a legal fiction. People coming in get nothing. They get so-called self-directed services with inadequate or no budgets.”

Kim Meehan, a COFAR member, talked about her successful effort last year to gain admission to Hogan for her legally blind and quadriplegic sister Kristen. But Kristen’s admission came only after a lengthy battle that included blog posts by COFAR in support, and coverage by Fox 25 news.

“There was no place for Kristen to go,” Kim said, explaining the situation her sister was facing while being kept for two months at Faulkner Hospital. “DDS kept using the verbiage that the community would be the ‘least restrictive’ setting for her. It didn’t matter to DDS that her doctor said she needed an ICF.”

Mitch Sikora, a COFAR Board member, recounted the landmark Ricci v. Okin litigation in the 1970s and 1980s that led to major improvements in state-run facilities that serve people with intellectual disabilities. Many aging people with intellectual disabilities, he noted, are in particular need ICF-level care because facilities such as Wrentham and Hogan are equipped and staffed to serve people with complex medical needs.

Sikora also discussed the comprehensive care his brother Stephen has received at Wrentham.

Both Shiri Ronen-Attia and Marsha Hunt pointed out that their sons are nonverbal, don’t socialize, and have no interest in group activities — characteristics that make them different from most people with developmental disabilities who are suitable candidates for community-based settings. “Group homes can’t meet their needs,” Ronen-Attia said. “They have no voice.”

Hunt said that her son “sits day after day with nothing to do.” He is not provided in his group home with the occupational, physical, or speech therapy that might enable him to make progress in those areas, she said.

As I noted, many group homes have become the new warehouses in which intellectually disabled people are now largely placed.

We also discussed the proposed legislation that Senator Feeney has agreed to draft. As Irene noted, the legislation was proposed some five months ago.

Correale said Feeney’s staff was still working on our legislative proposals, and was “trying to bring them to the Senate as an institution.” He said Feeney’s office has begun discussing the legislation with the co-chairs of the Children, Families, and Persons with Disabilities Committee.

COFAR has specifically asked Feeney’s office to draft language to be added to the ICF line item in the state budget, stating that persons who qualify for community-based care from DDS have a right to ICF care.

In sum, Friday’s meetings convinced us that if state-run ICF care is to be preserved in Massachusetts, advocacy efforts must continue, and should be combined, if possible, with the ongoing effort to save the Pappas Hospital. We recognize that this will be an uphill battle.

But the good news is that we got what seemed to be a sympathetic hearing on Friday from the staff members of the two legislators. What is needed going forward is for the lawmakers themselves to attend the advocacy sessions, and to publicly support the preservation of state-run care.

Wrentham and Hogan Center proponents to visit the State House on Friday

A group of advocates of the Wrentham and Hogan Intermediate Care Facilities (ICFs) is planning to meet with staff members of several state lawmakers at the State House in Boston tomorrow (Friday) in order to protect the facilities from eventual closure.

Many of the advocates are COFAR members. We also expect participation by members of the AFSCME Council 93 state employee union and the Massachusetts Nurses Association (MNA).

For anyone interested in joining us, we will first gather at 10 a.m. outside the cafe on the fourth floor of the State House.

As we have reported many times, Wrentham and Hogan are critically important to the fabric of care for people throughout the state with intellectual and developmental disabilities. But like many administrations before it, the Healey administration appears to be allowing ICF-level care in Massachusetts to die by attrition.

The Friday State House event, which is being organized by COFAR member Irene Tanzman, will involve meetings with the staffs of several legislators whose districts include or are near to the two facilities. (Irene, by the way, has set up a Facebook group devoted to saving Wrentham and Hogan. You can find and join the group here.)

The legislators whose staffs we will meet with include State Senator Paul Feeney, whom we have asked to draft legislation that would open the doors at Wrentham and Hogan to new admissions and establish housing on the campuses of the facilities for elderly family members of the residents.

FY ’26 state budget would provide some increase in ICF funding

Meanwhile, the Legislature’s Senate Ways and Means Committee released its Fiscal Year 2026 state budget plan on Tuesday of this week, which would provide for moderate increases in funding for the ICFs and state-operated group homes in Massachusetts.

Unfortunately, the SWM budget doesn’t include the language we are suggesting, which we hope would would open the doors to Wrentham and Hogan. Our proposed language to ICF line item in the budget states that persons eligible for Home and Community Based Services (HCBS) have a right to care in an ICF in Massachusetts.

We plan to ask Senator Feeney’s staff tomorrow about the status of that proposed legislative language, and to convey the importance to all of the legislators of saving Wrentham and Hogan as part of the continuum of care in this state.

The SWM budget adopts the governor’s proposed FY ’26 funding levels for Wrentham and Hogan and state-operated group home line items.

For the ICF line item (5930-1000), the SWM budget proposes an increase from $124,809,632 to $132,086,287. That’s a 5.8% increase from the current fiscal year, which is above the rate of inflation.

For the state-operated group home line item (5920-2010), the SWM budget proposes an increase from $330,698,351 to $362,028,812, which is a 9.5% increase. We are not sure why those line items are getting those increases, but they are welcome.

The SWM Committee has also adopted the governor’s proposed increase to the corporate provider group home line item to over $2 billion — a 19% hike in funding. That is about the twice the percentage increase that the state-operated group home line item would get.

As Irene has noted, tomorrow’s State House event is just a start in what we hope will be a long-term advocacy effort in support of state-run care for some of our most vulnerable citizens.

As with the embattled Pappas Rehabilitation Hospital, which the Healey administration has also targeted for closure, we hope the preservation of the Wrentham and Hogan Centers will garner critical public support. Without that support, those two essential centers of care will eventually die.

Family thanks DDS commissioner for referral of sister to the Wrentham Center

[Editor’s Note: We are reprinting a letter below that was written by Joan Norman, a sister of Ellen Gallagher. Ellen, who has an intellectual disability, had been living in a corporate, provider-run group home, which was moving to evict her because they admittedly couldn’t meet her needs.

Ellen has Alzheimer’s disease and limited mobility mainly due to limited vision issues and age. Joan describes her as “sweet and social,” but said she had been declining in the group home due the advancement of her disease and “sub-par medical and mental health care.”

In November, after advocacy on Ellen’s behalf by her family and members of COFAR, Department of Developmental Services (DDS) Commissioner Jane Ryder granted Ellen a rare admission to the Wrentham Developmental Center.

The number of residents at Wrentham and the Hogan Regional Center has been steadily declining for several years. That is because a succession of administrations has had a policy of declining to offer Wrentham or Hogan as residential options even when families ask for them.

We think Joan’s letter to Commissioner Ryder is an eloquent testimonial to the quality and importance of the care provided by state-run Intermediate Care Facilities (ICFs) such as the Wrentham and Hogan Centers.]

_____________________________________________________________________________________________

Dear Commissioner Ryder,

This letter is to formally thank you for supporting our sister’s referral to the Wrentham Developmental Center (WDC) back in November.

As you might remember, Ellen Gallagher, a 55-year-old Down Syndrome woman on hospice, with advanced Alzheimer’s, was living in her group home’s family room due to losing the ability to walk or get to her 2nd floor bedroom for almost 4 months.

We fought hard to find the appropriate placement with 24/7 nursing care so that Ellen could live out her remaining time with dignity and proper medical and mental health services. She needs services that include continuity and onsite care, rather than visiting the ER, hospital stays and unnecessary tests when she has had minor issues such as dehydration.

Now that she has settled in at WDC and has spent 6 weeks there, we can confirm it is an amazing living environment where her medical needs are finally being met and she is safe. She now has a handicap accessible bathroom and there are appropriate safety measures to match her abilities and changing needs.

We realize there is a push to keep people out of ICFs like WDC, but for medically complex clients it should be an option and it should be offered willingly by DDS. Families should not have to fight so hard for the care they need. ICFs are not the institutions of the past.

In this case, WDC is an example of the type of culture that is needed in community-based homes where a client’s medical care doesn’t involve neglect, safety issues and unprepared front-line workers.

We suspect costs are a driving factor behind limiting ICF placements. If you look at costs in community-based homes, many medically complex people end up with unnecessary emergent care because they don’t have onsite nursing care. Caretakers (with little to no medical background) use ambulances and hospitals “to be safe” when issues arise. Or worse, many clients go without proper medical care when they need it.

In my sister’s situation, in one incident, she was so dehydrated she ended up in the hospital nearly unconscious for days after being left virtually alone with a COVID infection. The staff handed her over to us after her isolation period, and we took her directly to the ER. She never gained back her strength, and it began a downward spiral of physical and mental decline for her.

In theory, nursing staff should be available to coordinate client medical care in group homes, but that is not how it often works. This can result in sub-par care, but also higher costs for the state’s Medicaid program when emergent care and unnecessary hospitalizations are used in place of qualified medical workers who can properly assess and address medical issues properly.

We urge you to continue supporting families who are seeking placements in an ICF like Wrentham, particularly for medically complex clients. Quality 24/7 medical care is not available in community-based homes, or it is patched together at best. WDC can offer this type of care.

There is a federal regulation supporting the choice of an ICF: Individuals seeking care, and their families and guardians, should be given the choice of either institutional or home and community-based services. [42 C.F.R. § 441.302(d)]. We got our choice for Ellen, and we sincerely thank you for supporting that decision. Please consider supporting others as well.

Sincerely,

The family of Ellen Gallagher

DDS confirms 91 vacancies in state-operated group homes even after several homes are shut

The Department of Developmental Services has confirmed for the first time that there are dozens of vacant beds in its state-operated group home network, even though the Department also says it has closed a net of nine homes since August 2021.

That information was provided to us in response to a Public Records Request, which we filed earlier this month with the Department.

In a response on September 26 to our request, DDS stated that as of June 30, there were 91 vacancies in the state-operated group home system.

COFAR has long contended that there are vacancies in state-operated homes because DDS generally does not inform individuals seeking residential placements of the existence of that system. Instead, DDS seeks to place virtually all persons in its much larger network of corporate provider-run group homes.

We are frequently told by families seeking placements for their loved ones in the state-run system that there are no vacancies in state-operated homes.

DDS also does not inform or generally admit persons to either of its two remaining Intermediate Care Facilities (ICFs) in the state – the Wrentham Developmental Center or the Hogan Regional Center. As a result, the number of residents living in state-run residential facilities has continued to decline, while the number in corporate run group homes has been steadily increasing.

COFAR has periodically filed Public Records requests with DDS to track the declining census in both the state-operated group home system and the Wrentham and Hogan Centers. The Wrentham and Hogan centers are the last remaining, congregate ICFs in the state.

DDS has continued to maintain that the corporate provider system is less restrictive and better integrated into the community than is the state-run residential system. However, as a Spotlight investigation by The Boston Globe showed on September 27, the corporate group home system is beset by abuse and neglect.

The data provided by DDS on September 26 show the following:

- There were 91 empty beds in state-operated group homes as of June 30. The Department, however, said it “does not have any responsive records” pertaining to COFAR’s request for the number of vacancies in the state-operated group homes each year from Fiscal Year 2019 to the present.

- The census, or total number of residents, at the Wrentham Center dropped by 48%, from 323 residents in Fiscal 2013, to 167 in Fiscal 2023.

- The census at Hogan dropped from 159 in Fiscal 2011, to 95 in Fiscal 2023, a 40% drop.

- The total census in the state-run group home system dropped by nearly 10% between Fiscal 2015 and 2021, according to previous DDS data. However, DDS has not provided information on the census in the state-run homes since 2021. We have appealed that apparent information denial to the state supervisor of public records.

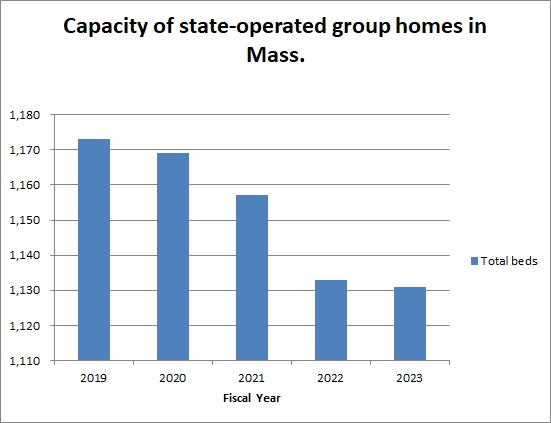

- The total capacity, or number of beds, in the state-run group home system declined by 3.6% from Fiscal Year 2019 to Fiscal 2023.

- DDS says it closed a net of nine state-operated homes between August 2021 and September of this year. As noted below, the numbers don’t appear to add up, however. We’ve appealed for clarification.

Declining capacity and census in state-operated group homes

As the chart we created below based on the DDS data shows, the total capacity or number of beds has continued to decline in state-run group homes. That capacity declined from 1,173 beds to 1,131 beds, or by 3.6%, between Fiscal 2019 and 2023.

Previous data from DDS showed that the total census in the state-operated group homes declined from a high of 1,206 in Fiscal 2015, to 1,097 in 2021 — a 9% drop.

DDS numbers don’t add up

In addition to appealing the lack of census information regarding the state-run group home system subsequent to 2021, we are appealing to the public records supervisor to seek clarification from DDS regarding an apparent discrepancy in the numbers the Department has given of homes that have been closed since 2021.

The September 2023 DDS response to our Public Records request indicated that a net of 9 state-run homes were closed between August 2021 and September 2023, leaving 251 homes remaining.

However, data previously provided in January indicated that a net of 6 state-run homes were closed between August 2021 and January 2023, leaving 250 homes remaining as of January.

The implication of the January data was that 256 homes existed as of August 2021, whereas the implication of the September data was that 260 homes existed as of August 2021.

We have asked the public records supervisor to require DDS to account for the apparent difference between the two responses in the number of homes that existed as of August 2021.

DDS consistently maintains it has no records regarding the future of state-operated care

Despite the continuing downward trend in the census at Wrentham and Hogan, DDS said in January and again in September that they have no records concerning projections of the future census of those facilities or concerning plans to close them. Nevertheless, we maintain that unless DDS opens the doors at those settings to new residents, they will eventually close.

Violation of federal law not to offer state-run facilities

In a June 5 legal brief, DDS argued that federal law does not give persons with intellectual or developmental disabilities the right to placement at either the Wrentham or Hogan Centers. We think the Department’s argument in the brief misrepresents federal law, and reflects an unfounded bias among policy makers in Massachusetts against ICFs.

As Medicaid.gov, the federal government’s official Medicaid website, explains, “States may not limit access to ICF/IID service, or make it subject to waiting lists, as they may for Home and Community Based Services (HCBS)” (my emphasis). In our view, the federal Medicaid law and its regulations confer the right to the choice of ICF care to individuals and their families and guardians.

Meetings with state and federal lawmakers to bring these concerns to their attention

Last week, we met online with state Representative Jay Livingstone, the new House chair of the state Legislature’s Children, Families, and Persons with Disabilities Committee, to raise our concern about the declining census in state-run facilities and to discuss their vital contribution to adequate care in the system. We are similarly seeking a meeting with Senator Robyn Kennedy, the new Senate chair of the committee.

So far, we have also met online with legislative staffs of U.S. Senators Elizabeth Warren and Ed Markey, and of U.S. Representatives James McGovern, Lori Trahan, Catherine Clark, Seth Moulton, and Stephen Lynch, and have imparted that message. We still have four additional members to meet with in the Massachusetts congressional delegation.

In our meetings with the staff members of the congressional delegation, we are urging that the lawmakers oppose pending bills that would expand funding to the largely privatized, community-based system, but would not direct similar funding to either Wrentham or Hogan.

In sum, the data we have gotten from DDS have shown a consistent pattern by multiple administrations of building up the privatized DDS group home system while letting state-run residential facilities wither and ultimately die. As we’ve said before, we think that will result in a race to the bottom in the quality of care in the DDS system.

In our experience, state-run residential facilities in Massachusetts, as in most other states, meet higher standards for care than do privatized settings, and tend to have higher paid, better trained, and more caring staff. We want to bring that message to our state and federal legislators before it’s too late.

DDS wrongly claims federal law does not give individuals the choice of either the Wrentham or Hogan Centers

In a June 5 legal brief, the Department of Developmental Services (DDS) argues that federal law does not give persons with intellectual or developmental disabilities (I/DD) the right to placement at either the Wrentham Developmental Center or the Hogan Regional Center.

We think the Department’s argument in the brief misrepresents federal law, and reflects an unfounded bias among policy makers in Massachusetts against Intermediate Care Facilities (ICFs). The Wrentham and Hogan centers are the last remaining, congregate ICFs in the state.

As we argue below, we also think the DDS brief wrongly assumes that group homes necessarily provide their residents with more integration with the surrounding community than do ICFs. That assumption is based on an outdated perception of the way ICFs operate today, and an overly rosy perception of the community-based system.

As we have reported, a succession of administrations has allowed the residential population or census at the Wrentham and Hogan centers to decline. This decline is due to DDS’s apparent policies of denying admission to the ICFs to most persons who ask for it, and failing to inform persons looking for placements that those facilities exist as residential options.

The DDS brief appears to confirm those policies in stating that:

DDS avoids institutionalization at the ICFs except in cases where there is a health or safety risk to the individual or others, and generally, when all other community-based options have been exhausted.

The DDS legal brief was submitted in response to an appeal to the Department, which was filed by the mother of a man with I/DD who was denied admission to the Wrentham Center. We are withholding the names of the mother and her son, at the mother’s request.

Federal Medicaid law requires a choice of either an ICF or “waiver services”

In our view, the DDS policies regarding admissions to ICFs do not comply with the federal Medicaid law and regulations. Those rules require that ICFs be offered as a choice to all persons whose intellectual disability makes them eligible for care under the Medicaid Home and Community-based Services (HCBS) waiver program.

Persons who are found to be eligible for HCBS waiver care have been found to meet the eligibility requirements for ICF-level care.

The HCBS waiver was established to allow states to develop group homes as alternatives to institutional care. However, the Medicaid statute did not abolish institutional or ICF care. In fact, the statute states that if a state does include ICFs in its “State Medicaid Plan,” as Massachusetts does, the state must provide that:

…all individuals wishing to make application for medical assistance under the (state) plan shall have the opportunity to do so, and that such assistance shall be furnished with reasonable promptness to all eligible individuals. [42 U.S.C. § 1396a(a)(8)]

Federal Medicaid regulations state explicitly that individuals seeking care, and their families and guardians, should be “given the choice of either institutional or home and community-based services. [42 C.F.R. § 441.302(d)] (My emphasis.)

The DDS brief, therefore, wrongly asserts that, “Federal law does not entitle the Appellant (the mother’s son) to admission to an Intermediate Care Facility.”

DDS brief wrongly assumes ICF settings are necessarily more restrictive than community-based group homes

The DDS brief also states, as a reason for denying admission to the Wrentham Center to the mother’s son in this case, that state regulations require the Department to place individuals “in the least restrictive and most community integrated setting possible.” According to the brief, the son currently lives in “a less restrictive community-based setting” than he would in an ICF such as the Wrentham Center.

But a statement that a community-based setting is necessarily less restrictive than an ICF is an ideological position that ignores the evidence.

This past Sunday, for example, I attended an annual birthday party for a DDS client who lives in a provider-run group home in Northborough. The home is located on a busy road. There is no sidewalk along the road, and only one other home in the area is faintly visible from the client’s residence.

There is no opportunity for the client to walk in the neighborhood around the residence, whereas residents at the Hogan and Wrentham Centers have access to acres of walking and recreational areas on the facility campuses.

While staff in the client’s Northborough group home do take him on trips to restaurants and other community events, those kinds of events are also provided, as our Board member Mitchell Sikora has recently described, to residents of the Wrentham and the Hogan Centers.

We’ve also written many times about restrictions imposed by DDS on visits and other types of contact by family members with residents of provider-run group homes.

The presumption that ICFs are necessarily more restrictive than group homes is based on an outdated characterization of facilities such as the Wrentham and Hogan Centers. Like many proponents of the privatization of DDS services, DDS chooses not to recognize the major improvements in congregate care and conditions that occurred, starting in the 1980s, in Massachusetts and other states as a result of both federal litigation and standards imposed by the Medicate statute.

DDS brief takes a we-know-best position

In addition to the questionable assumption it makes with regard to the level of restrictiveness of ICF care, the DDS brief also appears to accept, without question, that care and conditions in provider-run group homes are uniformly good.

The brief noted, for instance, that a DDS regional director had testified during a hearing in the case that the mother’s son “would not likely receive a greater benefit from admission to the ICF than he receives in the community.”

According to the brief, the son:

…has been successfully supported in the community for 13 years, his annual ISP (Individual Support Plan) assessments indicate that he continues to make progress toward his ISP goals, and he is well served by his community-based services and supports.

Conditions are not better in the community

Again, the DDS statements about what is best for an individual appear to be based on an ideological position that community-based placement options are always appropriate and available. In this case, however, the mother had sought to place her son at the Wrentham Center only after his group home provider had stated its intention to evict him from the residence.

The mother told us that in a meeting last year with DDS and provider officials, a provider manager cited two reasons for moving to evict her son. One was that her son had had a toileting accident on the deck of the group home, and that the mother had allegedly failed to notify the staff of the accident. The mother said the second reason was that she had posted a message on Facebook that was allegedly critical of the group home staff.

With regard to the toileting accident, the mother said she had taken her son back to the house after a planned outing, and that her son had the accident because the home was locked at the time and no one was there to let him in. Her son has Crohn’s Disease. The mother also said her son had also been physically abused on at least two occasions at the provider’s day habilitation facility.

Meanwhile, corporate group home and day program providers themselves in Massachusetts acknowledge that care and conditions in the DDS community-based system have been getting steadily worse.

In our view, all of this calls into question DDS’s assertion in the brief that the son in this case has been “successfully supported in the community for 13 years.”

DDS misrepresents the Olmstead Supreme Court decision

Finally, the DDS brief employs a common misrepresentation of the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1999 Olmstead v. L.C. decision with regard to institutional care. The brief wrongly implies that the Court held that in all cases, individuals should be placed in community-based rather than institutional settings. In fact, the Court held in Olmstead that three conditions must be met in order for persons to be placed in community-based care:

- The State’s treatment professionals determine that community-based placement is appropriate,

- The “affected persons” do not oppose such placement, and

- The community placement can be reasonably accommodated, taking into account the resources available to the state and the needs of others with mental disabilities.

The DDS brief, in arguing that Olmstead does not support the placement of the woman’s son at the Wrentham Center, cited only the first of the three conditions above. But all three conditions must hold under Olmstead in order to justify a placement in the community; and, clearly, the second condition doesn’t hold in this case — the affected persons do oppose continued placement in the community-based system.

In sum, the DDS closing brief in this case appears to provide the clearest indication we’ve seen of DDS’s reasoning and its policies with regard to admissions to the remaining ICFs in Massachusetts. It is clear to us that that reasoning and those policies are based on misinterpretations both of federal law and the history of congregate care for persons with I/DD in this state.

Unless the case can be made to key legislators and policy makers in Massachusetts that all family members and guardians should have the right to choose ICFs as residential options for their loved ones, the Wrentham and Hogan Centers will eventually be closed. If that happens, yet another critical piece of the fabric of care for many of the most vulnerable people in this state will be lost.

DDS may be violating federal law in not offering Wrentham and Hogan Centers as options for care

Recent reports from the Department of Developmental Services (DDS) to the state Legislature show a continually declining number of residents at the Wrentham Developmental Center and the Hogan Regional Center, and indicate there were no new admissions to either facility last year.

The reports have been submitted to the House and Senate Ways and Means Committees in compliance with a requirement each year in the state budget that DDS report on efforts “to close an ICF/IID (Intermediate Care Facility for individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities).”

The reports appear to confirm that DDS is not offering ICFs/IID (or ICFs/IDD) as an option to persons waiting for residential placements in the DDS system.

If so, that would appear to be a violation of the Home and Community Based waiver of the federal Medicaid Law (42 U.S.C. § 1396a(a)(8)), which states that intellectually disabled individuals have the right to ICF care.

In addition, the federal Rehabilitation Act (29 U.S.C., s. 794) states that no disabled person may be excluded or denied benefits from any program receiving federal funding.

The Wrentham and Hogan Centers, and three group homes at the former Templeton Developmental Center are the only remaining ICFs/IDD in the state. As such, they meet more stringent federal requirements for care and conditions than do other residential facilities, such as group homes, in the DDS Home and Community Based Services (HCBS) system.

The state budget language requiring reports on efforts to close ICFs/IDD appears to go back as far as Fiscal 2012, and it implies a bias in the Legislature against those facilities.

We were able to review the three most recent DDS reports to the Ways and Means Committees, for Calendar Years 2018, 2019, and 2020.

From 2018 to 2020, the reports state that the residential population or census at the Wrentham Center declined from 248 to 205, while admissions to the Center declined from only 2 in 2019, to 0 in 2020.

According to the DDS reports, the census at the Hogan Center declined from 119 in 2018 to 88 in 2020, while admissions declined from 18 in 2018, to 0 in 2020. (These census numbers don’t quite match up with other census data we have from the administration on the facilities, but all of the data show a continual decline in the census.)

Families largely satisfied with Wrentham and Hogan Center care

Based on the DDS reports, the decline in the census in both the Wrentham and Hogan Centers is largely due to deaths of residents in those facilities rather than discharges to the community system.

That would appear to support our observation over the years that parents and other family members of Hogan and Wrentham residents have been satisfied with the care at each of the Centers. If they were unsatisfied, they would have tried to seek community placements for their loved ones.

In our view, however, the DDS reports amount to a tacit admission by the Department that the Wrentham and Hogan Centers are eventually closing. The reports explicitly state that DDS will assure a “continuing ICF option” only for persons in the “Ricci class,” which are the dwindling number of people who are currently living in, or previously lived in, the state’s developmental centers.

Ben Ricci was the original plaintiff in the 1970s landmark federal class action lawsuit, Ricci v. Okin, that brought about upgrades in care for residents of the former Belchertown State School and other Massachusetts facilities for the developmentally disabled.

Those upgrades extended to the Wrentham and Hogan Centers. But the yearly DDS reports to the Legislature confirm our concern that DDS does not offer either the Wrentham or Hogan Centers as an option to people seeking residential placements for their loved ones with I/DD.

The declining census and admissions to the ICFs in Massachusetts are reflected in declining budget numbers for those facilities. In the DDS budget for Fiscal Year 2022, the corporate provider-run group home line item has been funded at more than $1.4 billion. That represents a 91% increase over the funding appropriated for the same line item a decade previously.

In contrast, funding for state-operated group homes and the remaining ICFs has been on a relatively flat or downward trajectory respectively.

Lack of understanding of the role of ICFs

At both the state and national levels, there is a lack of understanding of the critical need for ICFs/IDD and the fact that they that house and serve people with the most severe and profound levels of disability and medical issues.

There is a pervasive and deep-seated ideology that ICFs are overly institutional and prohibitively expensive to operate. But that ideology is misguided. As the VOR, an organization that advocates for persons with I/DD around the country, noted in a letter to the Senate Committee on Aging in Congress:

Community care does not provide the level or continuum of care needed by most of the I/DD population at the lowest level of these disabilities. Fewer necessary services are not proper care, and in the short-term (much less the long-term) do not provide necessary, life-sustaining care at the same cost level as ICFs.

Yet, the ideology at ICFs are no longer necessary can be found every year, as noted, in language in the Massachusetts budget.

Historical context of anti-ICF ideology

The anti-ICF stance of political leaders and policy makers and even many advocates for the disabled needs to be viewed in the historical context of the deinstitutionalization of people with mental illness and I/DD. That deinstitutionalization grew out of the warehouse conditions of the institutions prior to the 1980s.

Those anti-ICF advocates, however, have largely ignored upgrades in institutions, and particularly the efforts of the late U.S. District Court Judge Joseph L. Tauro, who oversaw the Ricci litigation that brought about improvements in institutional care in Massachusetts.

Deinstitutionalization has become a perfect storm of ideology and money that has kept a firm grip on our political system even though it has essentially been a failure for those it was meant to help. Deinstitutionalization has led to a tide of privatization of services for people with I/DD, and to skyrocketing salaries of executives of nonprofits that contact to provide residential and other care in the DDS system.

Proposed commission vulnerable to anti-ICF ideology

To this day, the anti-ICF ideology persists. At a June 21 legislative hearing in Massachusetts on a proposed state commission to study the history of state institutions for people with mental illness and I/DD, witness after witness denigrated ICF-level facilities as abusive and segregated from the wider community.

The hearing reinforced our concern that the makeup of the commission, as currently proposed, would provide fodder for those seeking to close the Wrentham and Hogan Centers.

As a result, we submitted testimony to a legislative committee considering bills to create the commission (S.1257 and H. 2090) that the commission should be reconstituted to recognize the significant upgrades in care and services that occurred in the state institutions as a result of the Ricci litigation overseen by Judge Tauro.

Calling for parity

That anti-ICF ideology is also reflected in President Biden’s American Jobs Plan, which includes $400 billion to expand access to Medicaid home and community-based services (HCBS) for seniors and people with disabilities.

In June, COFAR joined with AFSCME Council 93, a key Massachusetts state employee union, in warning that President Biden’s proposed $400 billion expansion of HCBS failed to provide any increase in funding for ICF-based care. As such, Biden’s plan could pose a threat to the future of ICF care and other state-run services.

In a jointly written letter to U.S. Senator Elizabeth Warren, COFAR President Thomas J. Frain and AFSCME Council 93 Executive Director Mark Bernard expressed overall support for the expansion of access to HCBS for people with I/DD and the elderly. But the letter noted that without the inclusion of additional funding for ICFs, Biden’s plan would create a strong incentive for Massachusetts to close the Wrentham and Hogan facilities.

As of mid-August, there has been no response to our joint letter from Senator Warren or her staff.

All of this shows how much of an uphill battle it has been to make the case for ICF-level care in Massachusetts and other states. We will continue to work to get the message get out, before it is too late, that ICFs provide a critical safety net of care for some of our most vulnerable members of society.

As the DDS reports to the Legislature show, however, time is running out.