Archive

DDS: We’re ‘not required to answer questions’ about the number of state-run group homes or of residents

As we have reported, the census or number of residents living in state-operated residential group homes and Intermediate Care Facilities (ICFs) in Massachusetts appears to be steadily declining.

But in response to Public Records requests filed by COFAR, first in January and then last month, the Department of Developmental Services (DDS) said it no longer has information on the actual number of people living in state-operated group homes during the past five years.

If it is true that DDS has no such records, it would indicate that the Department is unaware of the status of one of its most important operational programs.

DDS has also declined to clarify an apparent discrepancy in its claims concerning the number of state-operated group homes that have been closed since 2021.

We have appealed to the state’s public records supervisor in an effort to get clarification on those matters. In a response filed on Friday to our appeal, a DDS attorney said that under the Public Records Law, “an agency is not required to answer questions…”

Denial of group home information

Prior to this year, DDS did provide us with information on the declining census in state-operated group homes. That data showed a steady decline from a high of 1,206 residents in Fiscal Year 2015, to 1,097 in 2021. During that same time, the census in the much larger network of corporate, provider run group homes, also funded by DDS, rose from 7,793 to 8,290.

But as of January of this year, as noted, that information on the census in the state-operated group home system is apparently no longer available. What DDS said in January and again in September is that while it can provide information on the total available beds in, or capacity of, state-run group homes over the past five years, it now has no records on the census.

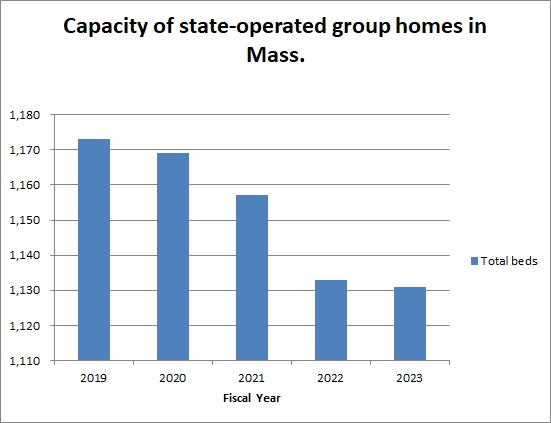

In September, DDS stated that the total capacity of the homes had declined from 1,173 beds to 1,131 beds between Fiscal 2019 and 2023.

But capacity numbers don’t tell the full story, particularly if DDS has not been allowing admissions to the group homes, and there consequently are vacancies in them. In fact, DDS acknowledged last month that there were 91 vacancies in the state-run group home system as of June of this year. That would imply that the actual census in the homes is lower than the capacity.

But DDS also said that while there were 91 vacancies as of June 30, it has no records on the number of vacancies each year since Fiscal Year 2019.

We calculated the apparent drop in the census as of Fiscal Year 2023

Based on the Department’s partial records, we did our own calculation of the census in the state-run group home network as of Fiscal Year 2023. That year, it appears the census would have dropped to 1,040.

That census or number of residents is based on DDS’s statement that the capacity of the state-run group homes was 1,131 in Fiscal 2023, and that there were 91 vacancies in the group homes as of June 30, the last day of that fiscal year. Subtracting the number of vacancies from the census that year equals 1,040. (1,131 minus 91).

If that is the case, it would indicate that the census in the state-run group homes dropped from 1,206 in Fiscal 2015 to 1,040 in Fiscal 2023, a 14% drop. See our chart below.

(Source: DDS. Note: We were not able to calculate the census in the state-run group homes in Fiscal Year 2022 because DDS did not provide a figure on the number of vacancies in that fiscal year.)

(Source: DDS. Note: We were not able to calculate the census in the state-run group homes in Fiscal Year 2022 because DDS did not provide a figure on the number of vacancies in that fiscal year.)

DDS will not clarify number of homes closed

As noted, DDS is not willing to clarify seemingly contradictory information on the number of group homes that have been closed and subsequently reopened since August 2021, during the height of the COVID crisis.

In September, DDS indicated that a net of nine state-run homes were closed between August 2021 and September 2023, leaving 251 homes remaining. However, eight months earlier – in January — DDS indicated that a net of six state-run homes were closed between August 2021 and January 2023, leaving 250 homes remaining as of January.

The implication of the January data was that 256 homes existed as of August 2021, whereas the implication of the September data was that 260 homes existed as of August 2021. The discrepancy might also mean that the number of homes that DDS said were closed may have been inaccurate.

However, as noted, when I asked that DDS provide clarification regarding that apparent discrepancy, a DDS attorney stated that, “Under the PRL (Public Records Law), an agency is not required to answer questions…”

The Public Records Law does require clarity

As part of our appeal, we stated to the public records supervisor that we believe DDS is, in fact, obligated to clarify information it provides under the Public Records Law.

The Massachusetts Guide to the Public Records Law, updated in March 2020, states that, “(State agencies) must help the requestor to determine the precise record or records responsive to a request…”

Also, the Public Records Law [M.G. L. c. 66, § 6A(b)] states that:

(The state agency) shall: …(i) assist persons seeking public records to identify the records sought;… and (iii) prepare guidelines that enable a person seeking access to public records in the custody of the agency or municipality to make informed requests regarding the availability of such public records electronically or otherwise…Each agency and municipality that maintains a website shall post the guidelines on its website.

In asking for clarification regarding the number of homes that existed as of August 2021 and have subsequently been closed, we were seeking the Department’s help in determining the precise record or records that might be responsive to our Public Records requests.

In sum, DDS’s response to our latest records requests seems to be part of the Department’s usual pattern of providing as little information as it feels it can get away with under the Public Records Law. The only other explanation is that the Department doesn’t have basic information about the programs it runs. We’re not sure which explanation is more troubling.

DDS confirms 91 vacancies in state-operated group homes even after several homes are shut

The Department of Developmental Services has confirmed for the first time that there are dozens of vacant beds in its state-operated group home network, even though the Department also says it has closed a net of nine homes since August 2021.

That information was provided to us in response to a Public Records Request, which we filed earlier this month with the Department.

In a response on September 26 to our request, DDS stated that as of June 30, there were 91 vacancies in the state-operated group home system.

COFAR has long contended that there are vacancies in state-operated homes because DDS generally does not inform individuals seeking residential placements of the existence of that system. Instead, DDS seeks to place virtually all persons in its much larger network of corporate provider-run group homes.

We are frequently told by families seeking placements for their loved ones in the state-run system that there are no vacancies in state-operated homes.

DDS also does not inform or generally admit persons to either of its two remaining Intermediate Care Facilities (ICFs) in the state – the Wrentham Developmental Center or the Hogan Regional Center. As a result, the number of residents living in state-run residential facilities has continued to decline, while the number in corporate run group homes has been steadily increasing.

COFAR has periodically filed Public Records requests with DDS to track the declining census in both the state-operated group home system and the Wrentham and Hogan Centers. The Wrentham and Hogan centers are the last remaining, congregate ICFs in the state.

DDS has continued to maintain that the corporate provider system is less restrictive and better integrated into the community than is the state-run residential system. However, as a Spotlight investigation by The Boston Globe showed on September 27, the corporate group home system is beset by abuse and neglect.

The data provided by DDS on September 26 show the following:

- There were 91 empty beds in state-operated group homes as of June 30. The Department, however, said it “does not have any responsive records” pertaining to COFAR’s request for the number of vacancies in the state-operated group homes each year from Fiscal Year 2019 to the present.

- The census, or total number of residents, at the Wrentham Center dropped by 48%, from 323 residents in Fiscal 2013, to 167 in Fiscal 2023.

- The census at Hogan dropped from 159 in Fiscal 2011, to 95 in Fiscal 2023, a 40% drop.

- The total census in the state-run group home system dropped by nearly 10% between Fiscal 2015 and 2021, according to previous DDS data. However, DDS has not provided information on the census in the state-run homes since 2021. We have appealed that apparent information denial to the state supervisor of public records.

- The total capacity, or number of beds, in the state-run group home system declined by 3.6% from Fiscal Year 2019 to Fiscal 2023.

- DDS says it closed a net of nine state-operated homes between August 2021 and September of this year. As noted below, the numbers don’t appear to add up, however. We’ve appealed for clarification.

Declining capacity and census in state-operated group homes

As the chart we created below based on the DDS data shows, the total capacity or number of beds has continued to decline in state-run group homes. That capacity declined from 1,173 beds to 1,131 beds, or by 3.6%, between Fiscal 2019 and 2023.

Previous data from DDS showed that the total census in the state-operated group homes declined from a high of 1,206 in Fiscal 2015, to 1,097 in 2021 — a 9% drop.

DDS numbers don’t add up

In addition to appealing the lack of census information regarding the state-run group home system subsequent to 2021, we are appealing to the public records supervisor to seek clarification from DDS regarding an apparent discrepancy in the numbers the Department has given of homes that have been closed since 2021.

The September 2023 DDS response to our Public Records request indicated that a net of 9 state-run homes were closed between August 2021 and September 2023, leaving 251 homes remaining.

However, data previously provided in January indicated that a net of 6 state-run homes were closed between August 2021 and January 2023, leaving 250 homes remaining as of January.

The implication of the January data was that 256 homes existed as of August 2021, whereas the implication of the September data was that 260 homes existed as of August 2021.

We have asked the public records supervisor to require DDS to account for the apparent difference between the two responses in the number of homes that existed as of August 2021.

DDS consistently maintains it has no records regarding the future of state-operated care

Despite the continuing downward trend in the census at Wrentham and Hogan, DDS said in January and again in September that they have no records concerning projections of the future census of those facilities or concerning plans to close them. Nevertheless, we maintain that unless DDS opens the doors at those settings to new residents, they will eventually close.

Violation of federal law not to offer state-run facilities

In a June 5 legal brief, DDS argued that federal law does not give persons with intellectual or developmental disabilities the right to placement at either the Wrentham or Hogan Centers. We think the Department’s argument in the brief misrepresents federal law, and reflects an unfounded bias among policy makers in Massachusetts against ICFs.

As Medicaid.gov, the federal government’s official Medicaid website, explains, “States may not limit access to ICF/IID service, or make it subject to waiting lists, as they may for Home and Community Based Services (HCBS)” (my emphasis). In our view, the federal Medicaid law and its regulations confer the right to the choice of ICF care to individuals and their families and guardians.

Meetings with state and federal lawmakers to bring these concerns to their attention

Last week, we met online with state Representative Jay Livingstone, the new House chair of the state Legislature’s Children, Families, and Persons with Disabilities Committee, to raise our concern about the declining census in state-run facilities and to discuss their vital contribution to adequate care in the system. We are similarly seeking a meeting with Senator Robyn Kennedy, the new Senate chair of the committee.

So far, we have also met online with legislative staffs of U.S. Senators Elizabeth Warren and Ed Markey, and of U.S. Representatives James McGovern, Lori Trahan, Catherine Clark, Seth Moulton, and Stephen Lynch, and have imparted that message. We still have four additional members to meet with in the Massachusetts congressional delegation.

In our meetings with the staff members of the congressional delegation, we are urging that the lawmakers oppose pending bills that would expand funding to the largely privatized, community-based system, but would not direct similar funding to either Wrentham or Hogan.

In sum, the data we have gotten from DDS have shown a consistent pattern by multiple administrations of building up the privatized DDS group home system while letting state-run residential facilities wither and ultimately die. As we’ve said before, we think that will result in a race to the bottom in the quality of care in the DDS system.

In our experience, state-run residential facilities in Massachusetts, as in most other states, meet higher standards for care than do privatized settings, and tend to have higher paid, better trained, and more caring staff. We want to bring that message to our state and federal legislators before it’s too late.

In ruling criticized as biased, DDS denies family’s request to place son at the Wrentham Center

As had been expected, Department of Developmental Services (DDS) Commissioner Jane Ryder last week upheld the denial of a request by a couple to place their intellectually disabled son at the Wrentham Developmental Center.

Ryder upheld a recommended decision by DDS Hearing Officer William O’Connell, who had previously denied a request by the couple to submit a COFAR blog post in rebuttal to a DDS closing brief in the case.

The COFAR post claims, among other things, that federal law gives individuals a right to care in an Intermediate Care Facility (ICF) such as the Wrentham Center.

The couple, who have asked that their names not be used, have sought the Wrentham placement as part of an appeal of their son’s Individual Support Plan (ISP). They contend the DDS-funded corporate provider that operates their son’s group home and day habilitation program does not provide services their son needs, such as nursing, speech and occupational therapy; and they note that these services are provided at Wrentham.

O’Connell’s 24-page recommended decision denying the couple’s appeal was dated July 20. The couple maintain that the language and reasoning in O’Connell’s decision confirms that he held a bias against them and in favor of DDS.

Son had been abused at day hab program and is facing eviction from group home

The couple also stated in their appeal that their son had been sexually and physically abused in his day hab facility. They further stated that the provider sought last September to evict their son from the group home after he had a toileting accident on the group home’s outside deck.

The eviction is currently on hold based on the couple’s objection to it under DDS regulations.

The couple said they are considering an appeal of O’Connell’s decision in state Superior Court. They said their hope is that a win in court would establish a precedent for other families seeking to place their loved ones with intellectual and developmental disabilities at either Wrentham or the Hogan Regional Center, the two remaining congregate ICFs in Massachusetts.

In ruling against the couple, O’Connell cited the testimony of two DDS regional directors during a hearing on the couple’s appeal in April. O’Connell stated that based on that testimony, he concluded that “the assessments and/or goals used to develop (the son’s) ISP…form a more than adequate basis for service planning for (the son), including his needs and treatments.”

O’Connell also stated in his decision that the son’s current services are “the ‘least restrictive’ to meet (his) current needs.”

O’Connell’s decision, however, largely did not address the couple’s contention that the actual services their son has received in his group home are inadequate.

Also, as COFAR pointed out in the blog post, which O’Connell would not allow to be submitted, “a statement that a community-based setting is necessarily less restrictive than an ICF is an ideological position that ignores the evidence.”

Hearing officer appeared to have a bias against the family

The couple further noted to us that the regional directors whose testimony was cited by O’Connell are bureaucrats who are largely unfamiliar with the day-to-day care of the son. Yet, the couple said, O’Connell clearly placed all of his credence in the directors’ testimony and not in their own testimony.

In his final decision, O’Connell used the term “credible” or “credibly” to describe the testimony of the two DDS regional directors at least 14 times, while repeatedly stating that the couple had “not met the burden of proof” and had not provided “probative evidence” to support their request that their son be placed at Wrentham. He didn’t explain why their evidence wasn’t probative.

The mother also told us that during the April hearing, O’Connell had expressed repeated impatience with her, telling her to “get to the point…” She said he never interrupted the DDS attorney.

O’Connell had also stated in his previous ruling that the COFAR Blog post was “not probative” as a reason for refusing to consider COFAR’s rebuttal to the DDS closing brief. The blog post would have required him to address several points including:

- That the federal Medicaid statute does provide a right and choice to individuals and their families to ICF care.

- That care at Wrentham and Hogan is not necessarily more restrictive than in provider-run group homes.

- That the couple’s son’s care in the community-based system has not been successful for the past 13 years, as the DDS closing brief stated, and O’Connell repeated.

- That DDS’s policy for many years of blocking new admissions to both Wrentham and Hogan is likely to result in the eventual closure of both of these vitally important backstops of care for some of the state’s most vulnerable residents.

In his decision, O’Connell also repeatedly stated that the couple had rejected all providers of community-based residential services that DDS had identified for them. But he did not acknowledge that the couple said they did so because they believe the community-based system has failed their son and will continue to do so.

ISP hearing process inherently unfair

COFAR has additionally questioned the fairness of the ISP appeal process, under which both the hearing officer is appointed by the DDS commissioner, and the commissioner then makes the final decision whether to uphold the hearing officer’s ruling. COFAR has called for such appeals to be decided by the state’s independent Division of Administrative Law Appeals.

Hearing officer discounted the impact of sexual and physical abuse of couple’s son

In his decision, O’Connell played down the impact of two incidents of sexual and physical abuse of the couple’s son, which the couple said were part of the reason they don’t believe the community-based system is safe or adequate for him. Both incidents had occurred in the bathroom of the day hab facility.

In one case in 2017, a staff member at the day hab program slapped the son on the head, punched him in the back, grabbed his genitals, and was verbally abusive to him over the course of several days.

In a second case in 2015, the son arrived from the day hab facility with a belt tightened so tightly that the parents couldn’t get it off. They said the belt was used to keep their son from going to the bathroom and moving his bowels. Their son has Crohn’s disease and needs to use the bathroom frequently.

According to the couple, their son cried and screamed when they tried to get the belt off. They said he had clear marks and indentations on his stomach which they photographed. In both cases, abuse was substantiated by the DDS investigations unit.

But O’Connell stated in his decision that:

I credit the (couple’s) concerns regarding (their son’s) well-being and safety given these terrible events, but find they were at day supports, not a residential placement, and thus do not have particular probative effect to the (couple’s) current appeal of the ISP and POC (Plan of Care).

O’Connell also stated, in line with the DDS closing brief, that the abuse happened five or more years ago.

But O’Connell didn’t mention that the same provider that runs the son’s day hab program also runs his group home. Also, there was no evidence presented by DDS or the hearing officer that abuse and neglect in the DDS provider system has become less prevalent in the past five years or that the abuse is unlikely to occur again.

Also, abuse in the provider system in general is not restricted to day programs, but occurs in residential settings. If the son were to be admitted to Wrentham, he would attend a day program there, where the abuse rate is likely to be lower than in the provider system.

We have found that abuse overall is lower in the ICFs than in provider run group homes.

Did not address specific services allegedly missing from the community

In a brief that they filed with their original appeal, the couple stated that there is no speech, occupational, recreational, or vocational therapy available to their son in his group home. The group home provider doesn’t provide those services, but Wrentham does.

The couple also stated that their son’s group home and day hab provider have not assigned a nurse to him or provided the name of a nurse to call in case a medical issue arises. They also said there is no nursing listed on his ISP or day hab service plan.

Also, the couple stated that no one at the group home “knows about (their son’s) health status at any given time.” For instance, they said, no member of the staff was aware their son was due for a colonoscopy in June.

The couple also maintained that in most doctors’ offices in the community, there are no accommodations for individuals like their son who have trouble waiting for long periods of time to be seen by the doctor.

O’Connell’s decision largely did not address these specific issues. However, O’Connell did respond to the couple’s contention that their son is not receiving the proper nursing care, writing that “DDS has indicated they will work with (the provider) and any subsequent residential agency to support (the son’s) specific nursing needs.”

The couple maintained to us, however, that saying DDS will “work with” the provider is a tacit admission that the service doesn’t currently exist, and is not an assurance that anything concrete will be done. Those nursing services, however, do exist at Wrentham.

O’Connell also stated that one of the DDS regional directors “credibly testified” that the couple had stated during an informal conference prior to the hearing that the son’s doctor is “excellent.” While that may be the case, the fact remains that the medical staff at Wrentham are highly trained to deal with people with intellectual disabilities, while medical staff in the community are not.

Also, O’Connell stated that the son’s difficulties in waiting at doctors’ officers “are common and easily managed by staff.” The parents disputed this, saying that if that behavior were easily managed, the problem would have been solved long ago.

Couple says son did not face discharge due to their actions

In his decision, O’Connell, once again adopting the DDS closing brief position, stated that the couple were notified last September that the son’s provider “was looking to discharge (him) from their residential placement services due to the (couple’s) actions, not due to any issue with (the son) or (the provider’s) ability to serve (the son).”

O’Connell did not say what those actions were that the parents allegedly committed. Moreover, the couple disputed O’Connell’s characterization of the matter. According to the couple’s original appeal brief, the incident that led to the discharge notice started when no staff were available in the residence to let their son inside to use the toilet.

The group home blamed the couple following the son’s accident on the group home deck, claiming they failed to clean up the area and failed to notify the staff about it. The couple dispute that charge, saying they used a sheet in their car to clean up the area and then emailed both provider and DDS officials about it.

The couple said there was one other incident that precipitated the discharge notice having to do with a Facebook post that the mother made that was critical of the staff of the group home. Neither of these incidents, in our view, are sufficient reasons to have issued a notice to evict the son. No details were provided in the hearing officer’s decision about either of those reasons for the discharge notice.

In sum, O’Connell’s decision in this case, in our view, shows exactly why the ISP appeal process is inherently unfair to families and guardians. His decision was entirely supportive of DDS’s position, and was entirely dismissive of the testimony and evidence put forth by the parents.

For the reasons the couple enumerated, we too hope they will win in court should they decide to appeal, and that this case would then set a precedent that might serve to save the Wrentham and Hogan Centers and other state-run residential programs and services from eventual extinction.

DDS hearing officer won’t allow COFAR blog post to be submitted as evidence in couple’s effort to place son at the Wrentham Center

A Department of Developmental Services (DDS) hearing officer has denied a couple’s request to submit a COFAR blog post to him for consideration as part of their appeal to place their son at the Wrentham Developmental Center.

The June 15 COFAR post claims, among other things, that federal law requires DDS to give individuals a choice of care in a facility such as the Wrentham Center. DDS primarily informs people looking for residential settings only of the existence of corporate provider-run group homes.

The couple, who have asked that their names not be used, requested that they be allowed to submit COFAR’s post in rebuttal to a DDS closing brief in the case. The DDS brief claimed that people with intellectual disabilities do not have a right to care at facilities such as Wrentham.

Last October, the couple appealed their son’s DDS Individual Support Plan (ISP) to the Department in an effort to have him placed at Wrentham. DDS held a hearing on the couple’s appeal on April 21 after the Department denied the requested placement. Under the ISP appeal regulations, the Department appointed a hearing officer in the couple’s case.

The hearing officer, William O’Connell, has not yet issued a decision on the appeal. His July 11 order denying consideration of the June 15 COFAR blog post stated that the post was submitted after his June 2 deadline for closing submissions in the case. However, O’Connell had previously extended that deadline to allow DDS to submit its closing brief on June 5.

Despite submitting its own brief under that extension, DDS subsequently opposed the couple’s request to have the COFAR rebuttal similarly entered into the record.

Hearing officer’s ruling is taken almost verbatim from DDS attorney’s objection

DDS’s written objection to the COFAR post described the post as “a late Rebuttal to the Department’s closing argument and brief,” and as “new evidence and argument that was not presented during the hearing or in the parties’ final closings.”

The DDS objection then stated that, “The (COFAR) evidence, a public opinion blog post, is of little probative value, and would likely not be admissible even if it were not filed late.”

Key portions of O’Connell’s written order about the COFAR blog post appear to have been taken almost word-for-word from DDS’s objection. O’Connell stated in his July 11 order that:

The (couple) submitted the rebuttal (COFAR post) well after the deadline for closing submissions had passed. Notwithstanding that the record was closed for evidentiary purposes at the close of the hearing on April 21, the proposed rebuttal to the DDS closing brief that the (couple) are attempting to submit as evidence and argument is a public opinion blog that is not probative and has no foundation for admissibility” (my emphasis).

Couple believes the hearing officer is biased against them

The couple maintain that O’Connell’s reliance in his order on the language in the DDS objection to the blog post appears to be evidence of a bias on his part in favor of DDS. They noted that he didn’t dispute any claim made in the post itself, but simply repeated DDS’s assertions about it.

The couple, who were not represented at the hearing by an attorney, also contended that O’Connell treated them with impatience during the April 21 hearing, and was deferential to DDS. “During the hearing, the hearing officer interrupted me several times and asked me to ‘get to the point,’” the wife said. “However, the DDS attorney was able to say her piece without interruption.”

The couple said they feel their case was “quite strong” at the hearing. But they said they are so certain their appeal will ultimately be denied by O’Connell that they are already planning their next move, which will be to take their case to state Superior Court to get their son into Wrentham.

If the couple are right about O’Connell’s likely decision, it will be interesting to see whether he primarily relies on the DDS closing brief in writing that decision, as he did with their request to submit our blog post into the record.

Unclear why DDS controls ISP appeal hearings

As noted above, DDS is in charge of the ISP appeal process, and even appoints the hearing officer who issues a recommended decision in each case. The final decision on the appeal is made by the DDS commissioner. We would agree that this creates, at best, a perception that the process is biased in favor of the Department.

We think the ISP appeal process should be decided by the independent Division of Administrative Law Appeals (DALA), which conducts appeal hearings for more than 20 state agencies, including the Disabled Persons Protection Commission (DPPC).

Hearing officer provided no support for claim that COFAR post was inadmissible

O’Connell stated that his order denying admission of the COFAR post was issued pursuant to the Massachusetts statute and regulations on adjudicatory practice and procedure (M.G.L. 30A and 801 CMR 1.02.)

We believe, however, that those rules would allow the post to be entered into the case record at any time, just as the DDS closing brief was entered after the hearing officer’s arbitrary closing date for submissions.

The regulations that O’Connell cited as underlying his ruling (801 CMR 1.02) constitute “informal rules” of adjudicatory procedure in Massachusetts.

Also, M.G.L.c. 30A, s. 11 states, with regard to the admissibility of evidence, that:

Unless otherwise provided by any law, agencies need not observe the rules of evidence observed by courts, but shall observe the rules of privilege recognized by law. Evidence may be admitted and given probative effect only if it is the kind of evidence on which reasonable persons are accustomed to rely in the conduct of serious affairs. Agencies may exclude unduly repetitious evidence, whether offered on direct examination or cross-examination of witnesses.

(3) Every party shall have the right to call and examine witnesses, to introduce exhibits, to cross-examine witnesses who testify, and to submit rebuttal evidence.

As we argue below, the COFAR blog post was intended to present evidence on which reasonable persons would rely in the conduct of serious affairs. It was not intended, as DDS and O’Connell casually dismissed it, to be a “public opinion blog.”

Both DDS and the hearing officer mischaracterized the nature of the COFAR blog post

As noted above, both DDS and O’Connell characterized the COFAR blog post as “a public opinion blog that is not probative and has no foundation for admissibility.”

However, the blog post directly rebutted the DDS assertion in its closing brief that federal law does not give persons with intellectual or developmental disabilities the right to placement at either the Wrentham Developmental Center or the Hogan Regional Center.

The post presented new evidence in the case regarding a succession of administrations in Massachusetts, which have allowed the residential population or census at the Wrentham and Hogan centers to decline. This decline, the post noted, has been due to DDS’s apparent policies of denying admission to those facilities to most persons who ask for it, and failing to inform persons looking for placements that those facilities exist as residential options.

We think the blog post therefore helped explain the almost automatic denial by DDS of the couple’s request to have their son placed at Wrentham.

Secondly, the blog post directly rebutted a statement in the DDS closing brief that the couple’s son currently lives in “a less restrictive community-based setting” than he would in an Intermediate Care Facility (ICF) such as the Wrentham Center.

The blog post then presented evidence that directly rebutted the DDS closing brief’s statement that the couple’s son “…has been successfully supported in the community for 13 years,” and that “he is well served by his community-based services and supports.”

Finally, the blog post revealed a misrepresentation in the DDS closing brief of the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1999 Olmstead v. L.C. decision with regard to institutional care. The post explained how the brief had wrongly implied that the Court had held that in all cases, individuals should be placed in community-based rather than institutional settings.

The statute that governs adjudicatory practice and procedure (M.G.L. c.30A, s.11), states that:

In all cases of delayed statement, or where subsequent amendment of the issues is necessary, sufficient time shall be allowed after full statement or amendment to afford all parties reasonable opportunity to prepare and present evidence and argument respecting the issues.

In our view, the couple were denied a reasonable opportunity to present evidence and argument in response to the evidence and argument in the DDS closing brief.

For all of the reasons discussed above, we believe the hearing officer erred in his denial of the couple’s request that the COFAR blog post be entered into evidence in their appeal.

DDS wrongly claims federal law does not give individuals the choice of either the Wrentham or Hogan Centers

In a June 5 legal brief, the Department of Developmental Services (DDS) argues that federal law does not give persons with intellectual or developmental disabilities (I/DD) the right to placement at either the Wrentham Developmental Center or the Hogan Regional Center.

We think the Department’s argument in the brief misrepresents federal law, and reflects an unfounded bias among policy makers in Massachusetts against Intermediate Care Facilities (ICFs). The Wrentham and Hogan centers are the last remaining, congregate ICFs in the state.

As we argue below, we also think the DDS brief wrongly assumes that group homes necessarily provide their residents with more integration with the surrounding community than do ICFs. That assumption is based on an outdated perception of the way ICFs operate today, and an overly rosy perception of the community-based system.

As we have reported, a succession of administrations has allowed the residential population or census at the Wrentham and Hogan centers to decline. This decline is due to DDS’s apparent policies of denying admission to the ICFs to most persons who ask for it, and failing to inform persons looking for placements that those facilities exist as residential options.

The DDS brief appears to confirm those policies in stating that:

DDS avoids institutionalization at the ICFs except in cases where there is a health or safety risk to the individual or others, and generally, when all other community-based options have been exhausted.

The DDS legal brief was submitted in response to an appeal to the Department, which was filed by the mother of a man with I/DD who was denied admission to the Wrentham Center. We are withholding the names of the mother and her son, at the mother’s request.

Federal Medicaid law requires a choice of either an ICF or “waiver services”

In our view, the DDS policies regarding admissions to ICFs do not comply with the federal Medicaid law and regulations. Those rules require that ICFs be offered as a choice to all persons whose intellectual disability makes them eligible for care under the Medicaid Home and Community-based Services (HCBS) waiver program.

Persons who are found to be eligible for HCBS waiver care have been found to meet the eligibility requirements for ICF-level care.

The HCBS waiver was established to allow states to develop group homes as alternatives to institutional care. However, the Medicaid statute did not abolish institutional or ICF care. In fact, the statute states that if a state does include ICFs in its “State Medicaid Plan,” as Massachusetts does, the state must provide that:

…all individuals wishing to make application for medical assistance under the (state) plan shall have the opportunity to do so, and that such assistance shall be furnished with reasonable promptness to all eligible individuals. [42 U.S.C. § 1396a(a)(8)]

Federal Medicaid regulations state explicitly that individuals seeking care, and their families and guardians, should be “given the choice of either institutional or home and community-based services. [42 C.F.R. § 441.302(d)] (My emphasis.)

The DDS brief, therefore, wrongly asserts that, “Federal law does not entitle the Appellant (the mother’s son) to admission to an Intermediate Care Facility.”

DDS brief wrongly assumes ICF settings are necessarily more restrictive than community-based group homes

The DDS brief also states, as a reason for denying admission to the Wrentham Center to the mother’s son in this case, that state regulations require the Department to place individuals “in the least restrictive and most community integrated setting possible.” According to the brief, the son currently lives in “a less restrictive community-based setting” than he would in an ICF such as the Wrentham Center.

But a statement that a community-based setting is necessarily less restrictive than an ICF is an ideological position that ignores the evidence.

This past Sunday, for example, I attended an annual birthday party for a DDS client who lives in a provider-run group home in Northborough. The home is located on a busy road. There is no sidewalk along the road, and only one other home in the area is faintly visible from the client’s residence.

There is no opportunity for the client to walk in the neighborhood around the residence, whereas residents at the Hogan and Wrentham Centers have access to acres of walking and recreational areas on the facility campuses.

While staff in the client’s Northborough group home do take him on trips to restaurants and other community events, those kinds of events are also provided, as our Board member Mitchell Sikora has recently described, to residents of the Wrentham and the Hogan Centers.

We’ve also written many times about restrictions imposed by DDS on visits and other types of contact by family members with residents of provider-run group homes.

The presumption that ICFs are necessarily more restrictive than group homes is based on an outdated characterization of facilities such as the Wrentham and Hogan Centers. Like many proponents of the privatization of DDS services, DDS chooses not to recognize the major improvements in congregate care and conditions that occurred, starting in the 1980s, in Massachusetts and other states as a result of both federal litigation and standards imposed by the Medicate statute.

DDS brief takes a we-know-best position

In addition to the questionable assumption it makes with regard to the level of restrictiveness of ICF care, the DDS brief also appears to accept, without question, that care and conditions in provider-run group homes are uniformly good.

The brief noted, for instance, that a DDS regional director had testified during a hearing in the case that the mother’s son “would not likely receive a greater benefit from admission to the ICF than he receives in the community.”

According to the brief, the son:

…has been successfully supported in the community for 13 years, his annual ISP (Individual Support Plan) assessments indicate that he continues to make progress toward his ISP goals, and he is well served by his community-based services and supports.

Conditions are not better in the community

Again, the DDS statements about what is best for an individual appear to be based on an ideological position that community-based placement options are always appropriate and available. In this case, however, the mother had sought to place her son at the Wrentham Center only after his group home provider had stated its intention to evict him from the residence.

The mother told us that in a meeting last year with DDS and provider officials, a provider manager cited two reasons for moving to evict her son. One was that her son had had a toileting accident on the deck of the group home, and that the mother had allegedly failed to notify the staff of the accident. The mother said the second reason was that she had posted a message on Facebook that was allegedly critical of the group home staff.

With regard to the toileting accident, the mother said she had taken her son back to the house after a planned outing, and that her son had the accident because the home was locked at the time and no one was there to let him in. Her son has Crohn’s Disease. The mother also said her son had also been physically abused on at least two occasions at the provider’s day habilitation facility.

Meanwhile, corporate group home and day program providers themselves in Massachusetts acknowledge that care and conditions in the DDS community-based system have been getting steadily worse.

In our view, all of this calls into question DDS’s assertion in the brief that the son in this case has been “successfully supported in the community for 13 years.”

DDS misrepresents the Olmstead Supreme Court decision

Finally, the DDS brief employs a common misrepresentation of the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1999 Olmstead v. L.C. decision with regard to institutional care. The brief wrongly implies that the Court held that in all cases, individuals should be placed in community-based rather than institutional settings. In fact, the Court held in Olmstead that three conditions must be met in order for persons to be placed in community-based care:

- The State’s treatment professionals determine that community-based placement is appropriate,

- The “affected persons” do not oppose such placement, and

- The community placement can be reasonably accommodated, taking into account the resources available to the state and the needs of others with mental disabilities.

The DDS brief, in arguing that Olmstead does not support the placement of the woman’s son at the Wrentham Center, cited only the first of the three conditions above. But all three conditions must hold under Olmstead in order to justify a placement in the community; and, clearly, the second condition doesn’t hold in this case — the affected persons do oppose continued placement in the community-based system.

In sum, the DDS closing brief in this case appears to provide the clearest indication we’ve seen of DDS’s reasoning and its policies with regard to admissions to the remaining ICFs in Massachusetts. It is clear to us that that reasoning and those policies are based on misinterpretations both of federal law and the history of congregate care for persons with I/DD in this state.

Unless the case can be made to key legislators and policy makers in Massachusetts that all family members and guardians should have the right to choose ICFs as residential options for their loved ones, the Wrentham and Hogan Centers will eventually be closed. If that happens, yet another critical piece of the fabric of care for many of the most vulnerable people in this state will be lost.

Retired Superior and Appeals Court judge writes about the care his brother receives at the Wrentham Developmental Center

[Editor’s Note: As we have previously reported, the number of residents remaining at the Wrentham Developmental Center and the Hogan Regional Center has continued to drop. As a result, these remaining, vitally important Intermediate Care Facilities (ICFs) in Massachusetts will eventually close if that decline is allowed to continue.

Mitchell Sikora, a member of COFAR’s Board of Directors, wrote the essay below about the importance of the Wrentham Center to his brother Stephen and himself, and submitted it to a member of U.S. Senator Ed Markey’s staff. We met last week on Zoom with one of the senator’s staff members to discuss our concerns about the future of the ICFs.

Mitch, 78, is a Massachusetts attorney and served as an assistant state attorney general for seven years; a private legal practitioner for 17 years; a justice of the Massachusetts Superior Court for 10 years; and a justice of the Massachusetts Appeals Court for 8 years. Since reaching the mandatory retirement at age 70, he has served as a voluntary mediator in the Superior Court.

We think Mitch’s account of the care that his brother receives at the Wrentham Center offers a clear explanation as to why ICFs are so important, and why eliminating those facilities as an option for care will be disastrous in Massachusetts.

It costs money to provide all of the specialists at Wrentham who care for Stephen and his fellow residents. But as we have seen, the closures of four of the six remaining ICFs in Massachusetts since 2012 has not resulted in a promised savings to the state. Over the past decade, the corporate provider-run group home line item in the state budget has grown from $760 million to $1.6 billion.

Moreover, We think Mitch’s list of recreational activities, both on-and-off-campus, that are provided to the residents at Wrentham debunks the myth that congregate-care facilities such as this one are institutional in character and warehouse or segregate those clients.]

My experience with ICFs in Massachusetts

By Mitchell Sikora

I am writing to report my experience with, and my support of, the continued operation of the remaining two ICFs for developmentally disabled residents of the commonwealth: the Wrentham Developmental Center in southeastern Massachusetts and the Hogan Regional Center in northeastern Massachusetts.

My younger brother Stephen, now 72 years old, has lived since age 10 at the Wrentham facility. The Center (originally named the Wrentham State School) has provided him with protection, care, affection, and community, especially since the major upgrade of all of the then Massachusetts state schools by federal district court litigation in the 1970s and 1980s, known collectively as the Ricci case and consent decree.

Since then, the Wrentham Center has functioned effectively as a campus village of concentrated human and physical resources benefitting Stephen enormously as he has aged.

I will do my best to describe the Wrentham Center’s human resources, its physical resources, and its communal benefits.

Human resources

The following personnel are assigned at the Wrentham Center to Stephen and each resident. A medical doctor oversees his health status. A nurse practitioner examines him promptly for any symptoms of illness. A daily staff nurse administers his medications and monitors his appearance.

His assigned social worker regularly visits him in his cottage dormitory and in socialization classes, and communicates her observations to us (his brother and sister).

A physical education specialist provides him with exercise at the Center’s gymnasium and swimming pool. A physical therapist has treated him for multiple orthopedic problems over the last 20 years, including knee replacements from arthritis, and hip and pelvic fractures from falls.

Vocational instructors have trained him to perform (to his own satisfaction) simple useful on-campus work, such as the collection and delivery of recyclable papers and objects. A recreational therapist periodically takes him for off-campus trips and treats, such as a stop at MacDonald’s. A psychologist responds to any episodes of behavioral or mood problems. A nutritionist watches his diet.

The Center also supports a “service specialist” program in which retired employees contract with families to take residents for off-campus rides or on trips to the families’ homes. Typically, the service specialists are familiar with the resident from years of work at the Center. With the fading of the COVID pandemic, the service specialist process can now resume.

Once each year, the Center must conduct a conference with each family to maintain and update the resident’s ongoing Individual Service Plan (ISP). The continuous Plan describes the resident’s health, activities, progress, problems, goals, needs, and spending objectives for the past and oncoming year. The Plan typically approximates 25 pages. The majority of the personnel enumerated above participate directly in the Conference (conducted by Zoom during the pandemic years) or contribute to the Plan.

As a final word about human resources, I should add that over the past 20 years, the Wrentham Center has received the dedicated service of three longtime facility directors and the involvement of devoted members of the Wrentham Family Association.

Physical resources

The Wrentham Center occupies a campus landscape of approximately 20 square blocks surrounded largely by open fields. The grounds include walking paths and picnic tables. The residents live in large cottages or small dormitories, each with a capacity of six to ten occupants.

Each resident has his or her own room. The communal bathrooms (with advanced shower facilities), kitchen, dining, and TV rooms are large and clean. Direct care workers are present at all times.

The campus contains a freestanding health care facility, the May Clinic, comprised of about 10 beds, three or four fulltime nurses, and visiting physicians. The Tufts Dental School maintains an office in the clinic.

The Wrentham Center has standing relationships with a number of hospitals, including New England Baptist for orthopedic care, and Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Sturdy Memorial Hospital, and Norwood Hospital for urgent and general care.

The campus buildings include a modern school structure of classrooms and meeting rooms; a gymnasium; a swimming pool; a canteen/snack bar; and two administrative buildings. Eight to 10 pre-1980s brick dormitories now long-abandoned remain scattered across the campus. The general setting is expansive and tranquil.

Communal benefits

A number of activities get the residents up and out of the cottage or dormitory:

- Physical ed classes at the gymnasium and pool. Classes at the school building in adult education, vocational education, and speaking skills.

- Day trips off campus to recreational parks, sports events, and the inevitable snack shops.

- The campus-wide Christmas decorations and party.

- A campus-wide spring celebration.

- A late summer week long country fair on campus conducted by a professional amusement company.

- Summer vacations of 3 or 4 days off campus conducted by staff and financed by families able to do so, or by the Center.

- The above mentioned service specialist program.

In all these activities the continuity and affection of the Center’s employees play a crucial role. Some of my brother’s caregivers have known and served him for more than 30 years.

My apologies for the length and detail of this message. I hope that it demonstrates the role of a well functioning ICF as a healthy community and home for its residents. It can serve as a unique concentration of both professional competence and elemental compassion.

A while back an old adage made a comeback: “It takes a village to raise a child.” I have thought that it applies even more so to the care of the developmentally disabled. At the very least, the families of the disabled deserve the informed choice of placement of their member in a well functioning ICF.

Since the great upgrade of the ICF system in the 1980s, the state has progressively reduced information made available to the public about the availability of the ICFs so that now only two ICFs remain in operation in Massachusetts. Those two facilities are subject to declining enrollment.

Post-Ricci administrations appear to retain a pre-Ricci vision of the care and conditions in the ICFs. That approach appears to have become dogmatic policy. It seems to me wrong upon several grounds. First, it is factually inaccurate and outdated. Second, it deprives applicant families of the opportunity of an informed placement choice. Third, it appears to violate requirements of both federal and state law that individuals and their families and guardians be able to make informed decisions about all available placements.

The federal Medicaid law and regulations require that individuals determined to be likely to need ICF-level care be informed of “the feasible alternatives” to that care, but also “given the choice of either institutional or home and community-based services.” [42 U.S.C.§ 1396n, and 42 C.F.R. § 441.302(d)].

However, as COFAR has often reported, families and guardians are generally not informed of the existence of the Wrentham or Hogan Centers. As such, those families and guardians are not being given the information or choices specified by the federal requirements.

Similarly, the Massachusetts Department of Developmental Services (DDS) regulations call for “informed consent” for admission to any departmental facility, including an ICF or group home. [115 CMR 3.04.] I suspect that additional sources of law and context would fortify the inherently fair and rational standard of informed consent and choice.

Faithful compliance with the legal standard of informed choice requires DDS to provide a family in need of a placement with a clear and explicit description of the ICFs and their resources and activities, and, if requested, with visiting tours of those facilities.

I hope that these thoughts are useful. Please do not hesitate to contact me for more information. Email: mitchsikora@gmail.com.

Father points out the personal impact of our neglect of adequate wages for caregivers

While the state provides almost $2 billion a year to privately run corporations to deliver a wide range of services to people with developmental disabilities, policy makers and legislators have historically been reluctant to fund even small increases in wages to actual caregivers.

In the case of parents of children with disabilities, the state provides no financial remuneration at all. At least one of those parents would like to see that changed.

We’ve written before about John Summers and his efforts to care for his non-speaking, autistic son Misha. In an opinion piece in The Boston Globe on May 18, Summers talks about the difficulty he has had in finding Personal Care Attendants (PCAs) to come to his home to help him provide daily care to Misha.

That difficulty Summers is facing is due to an ongoing staffing shortage that has afflicted virtually every facet of the state’s human services system since the start of the COVID pandemic some three years ago.

But there’s more to it than the lack of available staff. Summers, as a caregiver himself to his disabled son, receives no financial help from the state to do that work even though caring for Misha required him to leave his job and has dropped his income below the poverty line.

We have on many occasions called for adequate wages, benefits, and training for direct caregivers in the provider-run group home system funded by the Department of Developmental Services (DDS). The same neglect of the caregiver role exists when it comes to the funding of services to people living in their private homes, which is ostensibly where the state wants disabled people to live.

As Summers notes, “the concept (of PCA services) reflects a policy consensus that sustaining disabled people in their homes beats the alternative of institutional care.” Yet Summers contends the system as practiced today “cheats “ caregivers like himself.

Parents should be paid as caregivers

MassHealth allows consumers to hire just about anyone they want, including friends and relatives, to provide personal care services to themselves or others in their homes. But so-called “legally responsible relatives,” particularly parents, are barred from receiving state funding for caregiving.

As Summers points out in his article in the Globe, payment to legally responsible relatives is prohibited by the federal Medicaid law. But the state’s Home and Community Based Services (HCBS) waiver allows for the development of state programs that don’t meet specified Medicaid requirements. Payment of parents as caregivers is one such practice that can be permitted under the waiver. So far, however, MassHealth has not sought such permission from the federal government.

According to Summers, state legislators have filed bills since 2015 to allow legally responsible relatives and guardians to be paid for caregiving services. One such bill, S.775, is now before the Legislature’s Health Care Financing Committee.

Governor Healey, however, could act as well to seek such a waiver. Given the ongoing staffing shortage among PCAs and other caregivers, it would make a lot of sense to do so.

Governor labels PCA staffing shortage a priority

Summers points out that Governor Healey has pledged to place the “crisis-level” staffing shortages in the MassHealth Personal Care Attendant Program at the “top of her list.”

It is currently unknown, however, how many of the tens of thousands of persons who are enrolled in the state’s PCA program aren’t receiving PCA assistance due to the staffing shortages. The Healey administration needs to get a handle on that number for a number of reasons.

State funding for PCAs unspent

Summers, for instance, provided us with data he received from MassHealth on May 23, after he had filed a Public Records request for it. The data show the state appropriated more than $432 million in funding for personal care attendant services between 2012 and 2022 that was never spent, apparently because of a lack of available PCAs.

There is a keen irony here. More PCAs would become available if they were paid a living wage for their work. Instead, they are paid just $18 an hour, pursuant to a recent collective bargaining agreement.

The irony is that the $432 million in unspent funds implies there is enough money to boost the pay of caregivers in the human services system. While we have called for a raise to $25 an hour, Summers has suggested $50. So far, no one seems to have information on how much money is available or actually needed to fully address the direct-care wage problem.

Bureaucratic, privatized structure

What the state has done has been to perpetuate a privatized bureaucracy to administer the PCA program, just as it has built a largely privatized group home system funded by DDS. Summers believes the bureaucratic hurdles that the state has imposed have further discouraged people from applying to become PCAs and have led many to leave that profession.

As Summers points out, PCAs are paid though Tempus Unlimited, Inc., a private “fiscal intermediary.” Those workers will soon have to submit to a potentially intrusive process called Electronic Visit Verification, which is administered by Optum, another private firm.

It seems the state and federal governments are using the Electronic Visit Verification system to target PCAs for potential fraud. But are individual PCAs really committing most of that fraud, or does PCA fraud primarily take the form of improper billing by managers of the PCA provider companies? As usual, the direct care workers get few of the benefits of the system in which they work, but incur most of the blame. It’s apparently good politics.

Misplaced priorities

In sum, it appears the state has over-funded the PCA line item each year for the past 10 years, apparently due to continuing staffing shortages. Yet, the state could have used that funding each year to raise the hourly wages of the PCAs, which might have helped solve the staffing shortage problem.

There is also clearly more than enough funding available to pay parents such as Summers to enable them to care for their disabled children so that those parents are not forced into poverty.

It is not clear that the state has a handle on the extent of the PCA staffing shortage either or on the extent of potential fraud in the system. Yet, the state has created a privatized, bureaucratic administrative process for its PCA program that appears intended to inconvenience and place the blame on the very people who are the key to making the system work – the parents and caregivers.

We hope that in placing the PCA problems at the top of her list, Governor Healey will recognize and work to correct these misplaced priorities.

Mass Arc echoes our concern that DDS faces ‘systemic failure’ in providing services

Almost two years ago, we first reported that direct care staffing shortages were causing a potentially serious deterioration in residential and day program services in the Department of Developmental Services (DDS) system.

We have also reported repeatedly that the ongoing staffing shortages have caused worsening conditions in the group home system and a lack of meaningful activities in community-based day programs.

Now, the Arc of Massachusetts — an organization that lobbies for DDS residential and day program providers — is echoing our concerns. GBH News, citing the Arc, reported on April 27 that “up to 3,000 Massachusetts residents are waiting for a placement in these much-needed day programs, which are facing the same staffing shortages seen in other social service fields.”

The public radio news outlet quoted Maura Sullivan, a senior Mass Arc official, as saying:

There are thousands of adults with developmental disabilities that are not being served or we consider them underserved — very, very few services…

I think of it as really a systemic failure. And we’re really waking up to the fact that, you know, human services is a workforce that has been neglected in terms of rate increases. (my emphasis)

We would emphasize that we believe that thousands of Massachusetts residents are waiting not only for day program services, but for residential placements as well. In her remarks, Sullivan did not refer specifically to day program services, but to a lack of services in general.

The resources may be there

What the Arc isn’t saying is that the corporate providers are well funded in the state budget. The provider residential line item will have grown from $847 million, ten years ago, to more than $1.7 billion, under Governor Healey’s Fiscal Year 2024 budget proposal.

We think there is sufficient funding in the DDS system to provide needed services. It’s just that DDS isn’t using the resources in an optimal way. An example of that is DDS’s neglect of the ICFs and state-operated group homes as potential resources.

We have suggested to families whose loved ones are either receiving substandard services or are waiting for services that they ask DDS for placements in either the state-run Wrentham or Hogan ICFs, or in state-operated group homes. In the vast majority of those cases, however, we have heard that DDS has either not responded or pushed back on those requests.

While the state has continued to pour money into the corporate provider system, the number of residents in the state’s state-operated group homes and state-run ICFs have continued to drop.

As of the fall of 2021, we heard that state-operated group homes were being closed, and last month, we received records from DDS indicating that those closures were the result of insufficient staffing of corporate provider-run group homes. Yet, the records also indicated that the state-operated group homes continued to have vacancies.

Poor pay of direct care workers not the result of a lack of resources

We agree with the Arc that the human services direct care workforce continues to be grossly underpaid, and that this is a primary reason for the continuing staffing shortages.

Where we disagree with the Arc is that it once again doesn’t appear to us that the problem of low pay for direct care workers is necessarily due to a lack of resources.

The increases in state funding to the providers over the past decade have resulted in continuing increases in the pay of the provider executives. The increased state funding, however, hasn’t been passed through by the providers to their direct care employees.

We hope the Healey administration is open to a new approach to this problem. The new administration needs to redirect more of the state’s resources to state-run programs, and needs to ensure that those resources get to those who underpin the entire system — the direct care workers.

Mother gets little response to concerns about care of her disabled son in group home

Early on a Saturday morning last June, Ian Murawski phoned his mother Rachel Surner from his group home in Ashland, where he had been living for about a month.

Ian, 30, has an intellectual disability and has spastic quadriplegia, a condition that has left him with the limited ability to move only his arms. He is a talented singer, however, and Rachel describes him as having “amazing harmonies.”

It was 5:30 in the morning, and Ian said he needed to urinate, but that his bedside urinal was out of his reach. Rachel suggested he ring a bell near his bed, but Ian said the bell had fallen on the floor. She said she advised her son to yell for help.

About 15 or 20 minutes later, Rachel texted Ian asking if he had gotten help. He said “no”; so, at 6:45 a.m., she drove to the Ashland residence from her home about 10 minutes away in Holliston.

Rachel said that as she stood at the front door of the group home, waiting for someone to answer, she could hear Ian yelling inside for help. The home is run by the Justice Resource Institute (JRI), a corporate provider to the Department of Developmental Services (DDS).

After she rang the bell, a staff worker came to the door. She said she explained she was Ian’s mother, and Ian had been calling for help since 5:30.

No answer, just ‘intimidation’

Rachel said the staff worker did not want to let her in, but she brushed past him and walked inside anyway. “At that point, I was going in to help my son and find out why he didn’t have the things he needed or wasn’t getting help.”

She said that when she went into her son’s room, she saw that his urinal, which was supposed to be on his bedside table, was on the floor.

She brought the urinal to her son and tried to leave the room to give him privacy. But she said the staff member was now blocking the door to the bedroom and wouldn’t move to let her out.

When she insisted on being allowed to leave the room, the staff member reluctantly moved slightly to let her out. She said he then asked her to go stand by the front door and stated, “’You can’t just come here, just show up at any time.’”

“I informed him that Ian had been requesting help since 5:30,” Rachel said. “I asked why he was not assisted, but I got no answer, only a demand, intimidation and questions back.” She said the staff member did at one point say he was unaware Ian needed help, “to which I informed him that I could hear him while I was standing at front door!”

All of the details related above were contained in an email that Rachel sent on June 20, two days after the incident, to multiple DDS and JRI officials. She said she received no immediate response from anyone to her email.

On June 28, eight days after Rachel had sent her email, Ian’s then DDS service coordinator, emailed many of the same officials to express concern that JRI was not directly responding to Rachel’s concerns.

“If Ian is in distress in any way, please let us know!” the service coordinator’s email stated. “We would like to be aware so we can talk as a team and see if there are additional supports we can put in place to help… I also think we should hold another larger team meeting just as a check in, to hear Rachel’s observations and see if we can change our approaches moving forward.”

Rachel said the service coordinator later left to work in another DDS area office closer to where he lives.

Problems throughout provider system

Rachel is one of many family members and guardians of DDS clients who have been contacting us in recent months about what appear to be worsening conditions in the Department’s provider-run group home system.

We have suggested to Rachel and many other parents that they ask DDS for new placements for their loved ones in either the state-run Wrentham or Hogan Intermediate Care Facilities (ICFs), or in state-operated group homes. In the vast majority of those cases, however, we have heard that DDS has either not responded or pushed back on those requests.

In most of these cases, the care issues we hear about are numerous and interrelated.

Need for intensive care

Ian had encephalitis when he was a baby, which caused brain damage, cognitive delays, and mental health issues, Rachel said. He doesn’t require a ventilator or g-tube or significant drugs other than mental health medications. But he does need intensive physical care.

Rachel said her son can feed himself, but he can’t shower or toilet himself. She said he has been left at times by the staff to sit in his urine and feces.

Rachel said that while Ian has needed periodic psychiatric hospitalizations, she hasn’t been able to get him placed in most psychiatric hospitals because he is quadriplegic and requires too much care. He has been admitted to Mass. General Hospital on occasion, she said, but only when she has brought him directly to the ER “which is often very hard to do during a crisis situation.”

Prior to moving to the group home, Ian had lived at home. From age 10 to 18, he was at the Mass. Hospital School in Canton.

Rachel said Ian requires 1-on-1 care, but he is not getting that in the group home. There are supposed to be two staff members available when he’s at the house, but sometimes there is only one staff there to care for him and one or more other residents. His group home has four residents. The other residents are able-bodied and high functioning.

Last year, Rachel reported to DDS that Ian had bed sores. She said she has not been informed as to whether the Department investigated the matter or issued a report.

She said the group home staff also make mistakes with Ian’s medications. He is on Risperidone, Ativan, and Loxapine, which are used to treat schizophrenia. At times, he seems as if he is over-medicated. He seems “really out of it,” she said.

Accusations by JRI

Rachel said that earlier this month, a staff worker accused her and two family members of going into the group home, yelling, and breaking things. She said she was with Ian’s twin brother and his stepfather, and that at no time were they disruptive. She said she visits the home just about every day. Now, she said, when she and family members visit, they turn on their video cameras to document what is happening.

Rachel said that in a recent meeting with DDS officials, a JRI manager accused her of abusing the staff, and threatened to immediately discharge Ian because of that. She said the DDS officials, who were at the meeting, were caught off guard by this. They later told Rachel they had no record of any complaints about her. But nothing has been resolved, she said.

Lack of toileting

Despite the former service coordinator’s efforts, Rachel said the group home’s failure to attend to Ian’s toileting needs continued in the ensuing months. The incident related above about Ian’s urinal wasn’t the last time he was left without help when needing to use toileting facilities.

In a July 18 email to DDS and JRI officials, Rachel wrote that she had just visited her son and found him in clothing that was soiled with urine and feces. No staff member was available, so she cleaned her son up herself, but couldn’t find a change of clean clothing in his dresser drawers.

Rachel said that when she went looking for the staff, she found them sitting in the living room on their phones. The response she received from the staff was that “a.m. staff had not done laundry and it was washing now.”

“Although there are a few issues here,” Rachel stated in her email, “the biggest is he was sitting in soiled shorts, which he would have been for hours if I hadn’t come and cleaned him up. This is not o.k.”

The problem was not resolved, however. In an October 3 email to DDS and JRI — more than two months later — Rachel said that when she had picked Ian up at the group home the previous Saturday for a family dinner, he was inappropriately dressed in shorts and a t-shirt, and that his shorts were soiled. She and her husband got him cleaned up and “properly dressed.”

When they arrived back at the home at 7 p.m. that evening, there was only one staff member there, Rachel wrote. As with other problems regarding care in the group home, the toileting problem has persisted to the present day, Rachel told us.

Lack of showering

Rachel has also emailed DDS and JRI officials on several occasions to express her concern that Ian has not been regularly showered at the group home. In a July 5 email, she noted that she had noticed over the previous week that Ian had been going for several days at a time without a shower. In one case in which he had accidentally soiled himself, he was not showered afterward, she said.

Rachel added that when she messaged the JRI program manager to request that he ask the staff to shower Ian, she received a reply from the program manager that he was “‘looking for someone to shower him, but no one was around.’”

“This should not be something that goes days on end without happening, nor should it be something I need to ask for,” Rachel stated in the July 5 email. “Personal hygiene is necessary and also imperative in keeping skin clean, healthy and preventing breakdown.”

But the showering problem was not resolved. In the same October 3 email in which she had described the continuing toileting problem, she described a continuing lack of showering.

“Ian, having been soiled and not showered in the previous two days, needed a shower,” Rachel stated in the October 3 email. She said she was going suggest that Ian be given a shower upon arriving back at the goup home after the family dinner that previous Saturday evening. But she said she didn’t suggest it because there was still only one staff member there. She said she spent 45 minutes getting Ian ready for bed because the single staff member was busy with the other residents.

Yet, as of the following Monday morning, October 3, Ian still hadn’t been showered, Rachel said in the email. “Not only is this a violation on the requirements for the house, but Ian needed care and God forbid there were a real emergency!” she wrote.

Ian singing with two musician friends, Chris Fitz and Steve Dineen, at a local venue in Ashland. Rachel first introduced Ian to the duo about seven years ago.

Left in pain

An additional problem that apparently took months for the staff to address was back pain that Ian had regularly suffered from. Emails from last June through September indicate that this problem was not resolved in that period.

In a June 27 email to JRI and DDS officials, Rachel said Ian had been complaining about his back, and thought it might be due to his mattress. She noted, though that the mattress was “a very good Tempur-Pedic mattress and almost identical to the one he has at home.”

Two months later, on August 27, Rachel wrote that Ian’s back pain was continuing. She noted that while his doctor had prescribed Advil, an anti-inflammatory, for the pain, the staff was giving him only small amounts of Tylenol, which wasn’t helping.

She said that when she had tried to reposition Ian in his bed a few days before, he had screamed in pain and said his back was spasming. She immediately asked the staff for Advil for him, but was told none was available.

Yet, when Ian’s stepfather brought Advil to the house the following day, he was told the staff did have Advil.

“At this point, I think he needs to see a doctor, PT and perhaps have a muscle relaxer for when things get as bad as they have,” she wrote.