Archive

State House approves cuts to DDS day program funding, increases for provider group homes

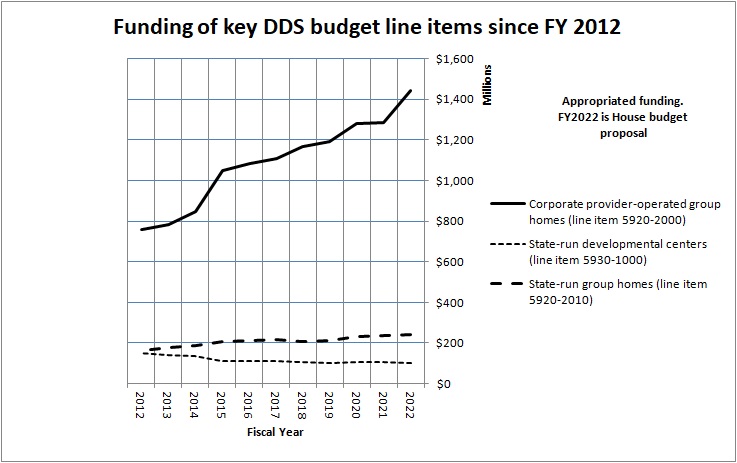

The House budget would add $100,000 to the governor’s proposed Fiscal 2022 funding for state-operated group homes (line item 5920-2010). However, when adjusted for inflation, even the House budget proposal would amount to a cut in funding for this line item of somewhat less than 1%. (We are basing that assessment on numbers from the Massachusetts Budget and Policy Center’s “Budget Browser.”)

The two remaining developmental centers would similarly see their funding cut in Fiscal Year 2022 by $2.1 million under the House budget, when adjusted for inflation (line item 5930-1000). Since Fiscal 2012, funding for the developmental center line item will have been cut by 32%.

COFAR is continuing to raise concerns regarding the ongoing under-funding of state-run DDS programs. We believe this has led to unchecked privatization of programs and services.

We are also concerned that even within provider accounts, we may be seeing a permanent pullback in funding for day programming, with much of that funding ultimately going to provider-run group homes.

Last month, we sent an issue paper raising those concerns, among others, to Senator Adam Gomez and Representative Michael Finn, the new chairs of the Legislature’s Children, Families, and Persons with Disabilities committee. You can find our issue paper here.

Congress still trying to eliminate congregate care for developmentally disabled

In their latest attempt to do away with congregate care for persons with intellectual and developmental disabilities and promote further privatization of services, lawmakers in Washington have proposed the Home and Community Based Services Access Act (HCBS Access Act).

While we support the intent of this legislation to eliminate waiting lists for disability services, the bill’s provisions are heavily biased against congregate care facilities such as the Wrentham Developmental Center and the Hogan Regional Center in Massachusetts. The bill is also biased against sheltered workshops and other programs for people who are unable to handle mainstream or community-based settings.

In that regard, this legislation is similar to the federal Disability Integration Act of 2019, which ultimately did not pass in the previous congressional session.

While we think it was good news that the Disability Integration Act didn’t pass, the bad news is that many in Congress, including most, if not all, of the Massachusetts delegation, appear to subscribe to the notion that community-based or privatized care is the only appropriate option for people with cognitive disabilities.

Every member of the Massachusetts delegation signed on to the Disability Integration Act, which would have encouraged further unchecked privatization of human services, diminished oversight, and reduced standards of care across the country. The HCBS Access Act would do so as well.

Comments are due April 26 on the HCBS Access Act, which has been proposed by Representative Debbie Dingell (D-MI), Senator Maggie Hassan (D-NH), Senator Bob Casey (D-PA), and Senator Sherrod Brown (D-OH). Comments can be sent to HCBSComments@aging.senate.gov.

We will also be urging the members of the Massachusetts delegation to take another look at the issue of congregate care, and reassess their positions.

The HCBS Access Act actually appears to go a step beyond the Disability Integration Act in that it would potentially eliminate funding for Intermediate care facilities (ICFs), including the Wrentham and Hogan Centers. Currently, the federal government pays 50% of the cost of care in both ICFs and community-based group homes. The state pays the other 50% of the cost.

The HCBS Access Act would change that federal-state funding formula to require the federal government to pay 100% of community-based group home costs. The federal share of the cost of ICFs would remain at 50%. That would place enormous pressure on states to eliminate ICFs since they would continue to receive only 50% federal funding.

As the National Council on Severe Autism (NCSA), a nonprofit organization, noted in comments on the HCBS Access Act, ICFs are “a key component of the national safety net.” The organization pointed out that it is a “fiction” that all community-based settings are better or safer than settings labeled as “institutional.”

“’Community services’ in reality often mean no supervision, no licensing, no consulting medical or nursing personnel, no properly trained staff to handle medical/behavioral crises, high burnout and turnover,” the NCSA stated in its comments.

Among the many unanswered questions involving the HCBS Access Act are how the federal government would pay the cost of 100% reimbursement of all community-based care.

The NCSA made a number of additional observations about the legislation, including the following:

- The bill is based on a “false assumption that the Medicaid system contains an ‘institutional bias’ that keeps adults with disabilities locked away from the community at large.

The NCSA noted that the steady closure of ICFs and sheltered workshops around the country in recent years “has already had the devastating impact of depriving individuals of critical options.”

- The bill would only support “supported (integrated or community-based) employment and integrated day services.”

According to the NCSA, the bill “could shutter desperately needed programs serving the severely disabled who are incapable of participating in integrated day services owing to their severe cognitive, behavioral, medical and functional challenges.”

We have been raising these same concerns about the closures of ICFs and sheltered workshops in Massachusetts for many years.

- The bill overlooks the difficulty of finding housing in the community for persons with autism, and the possibility of eviction for those with dangerous or disruptive behaviors.

We have also noted the potential for isolation of community-based group home residents whose guardians are perceived as troublesome or meddlesome

- The bill would establish an “advisory committee” that would place veto power in the hands of a few advocates. The NCSA stated that “a small, unelected and unaccountable committee would be handed broad discretion to determine what qualifies as HCB services across the country, trumping whatever needs and preferences of severely disabled individuals,”

As we noted about the Disability Integration Act, this new legislation does not comply with the choice provision in the Olmstead v. L.C. U.S. Supreme Court case. In 1999, the late Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, who wrote the majority opinion in Olmstead, endorsed the idea of a continuum of care for the most vulnerable members of our society. Her decision and message were models of inclusivity.

We urge people to email the Senate Special Committee on Aging, as we plan to do, at HCBSComments@aging.senate.gov. Feel free either to paste in this blog post or forward a link to it, along with a short message in opposition to the HCBS Access Act as currently written.

Fernald may be closed, but it’s still being blamed for the ills of the DDS system

The Fernald Developmental Center in Waltham has been closed for some seven years.

But activists who oppose all forms of congregate care are still making the former facility a focus of blame for the failures of the state’s care for people with developmental disabilities, even if it means portraying only one side of Fernald’s history.

It appears the latest effort to denigrate Fernald is a scheduled Zoom panel discussion being sponsored on March 10 by the Harvard Law School.

The discussion, titled “Fernald’s Legacy,” will feature Alex Green, a leader of a protest of a holiday light show late last year on the Fernald campus. Green started a petition last fall to stop the light show, contending a festive show on the campus would be “inappropriate, given (Fernald’s) history of human rights abuses and experimentation on children.”

A promotional text for the upcoming Harvard panel discussion refers to the legacy of institutions such as Fernald as “lurid,” and states that society must “critically and publicly interrogate the role they played in shaping today’s services, systems, and attitudes for persons with disabilities.” (my emphasis)

But dismissing the entire legacy and history of Fernald and similar facilities in Massachusetts as lurid may in fact be failing to “critically interrogate” their role.

Fernald was not the same institution by 1993 that it had been in 1970

Fernald’s past is, of course, notorious and controversial. Until the early 1980s, Fernald and other similar state-run centers were indeed horrendous warehouses of abuse and neglect.

In fact, many of COFAR’s members were plaintiffs in Ricci v. Okin, a combined class-action lawsuit first brought in the early 1970s by the late activist Benjamin Ricci over the conditions at the Belchertown State School. The Ricci lawsuit resulted in a consent decree that included the then Belchertown, Fernald, Wrentham, Dever, Monson, and Templeton state schools.

It was due to the dedication of the late U.S. District Court Judge Joseph L. Tauro in overseeing the consent decree that conditions at Fernald and the other state schools finally began to change.

What Green and other activists fail to understand or acknowledge is the revolutionary change that occurred at Fernald and the other institutions as a result of the litigation and Judge Tauro’s intervention. But acknowledging that change would be inconvenient if their purpose is to portray all congregate care, even as it exists today, as uniformly bad.

We have encountered this one-sided viewpoint repeatedly over the years among advocates, politicians, public administrators, and journalists.

That viewpoint betrays a lack of understanding of the history of care of the disabled in Massachusetts and elsewhere around the country. It also shows a lack of understanding of the strict federal standards under Title XIX of the Social Security Act that state-run developmental centers, also known today as Intermediate Care Facilities (ICFs), must meet.

Acknowledging the change that occurred at Fernald is also inconvenient for corporate group home providers to the Department of Developmental Services (DDS) and their lobbyists such as the Arc of Massachusetts. Since Fiscal 2014, when Fernald was closed, the DDS provider residential line item in the Massachusetts budget has risen by $354 million, or 37%, when adjusted for inflation.

That may explain why the Arc signed on to Green’s petition to stop the light show at Fernald, and why the Arc continues to lobby in favor of further closures of congregate-care facilities and further privatization of DDS services.

Our request to be on the Harvard Law School panel was not accepted

On Monday (March 1), I sent a detailed email to Green and to William P. Alford, chair, and Michael Stein, executive director of the Harvard Law School Project on Disability, which is hosting the panel discussion. In the email, I tried to present a balanced view of Fernald’s legacy, and suggested that the panel include at least one person who is aware of Fernald’s full history and understands its real meaning and importance. Tom Frain, our Board president, was willing to fulfill that role on the panel.

Yesterday, I received a 3-sentence response from Professor Stein, saying only that the event is open to the public and that we should “be respectful of the views expressed by our panelists.” He didn’t accept our offer to serve on the panel. Presumably, the most we would be allowed to do is participate in a question-and-answer session at the end of the discussion. As a result, we will pass on attending what is likely to be a one-sided event.

Stein’s email to me did not acknowledge, much less respond to any of the points I had raised about Fernald’s legacy.

The following are the points I made in my original email to Stein, Alford, and Green:

Judge Tauro attested to the improvements at Fernald

Judge Tauro, who died in November 2018 at the age of 87, had visited Fernald, Belchertown and the other Massachusetts facilities in the early 1970s to observe the conditions first hand. He noted two decades later in his 1993 disengagement order from the consent decree that the legal process had resulted in major capital and staffing improvements to the facilities and a program of community placements.

Those improvements and placements, Judge Tauro wrote, had “taken people with mental retardation from the snake pit, human warehouse environment of two decades ago, to the point where Massachusetts now has a system of care and habilitation that is probably second to none anywhere in the world.”

It is unfortunate that in a media release that Green wrote in November about the protest of the planned light show at Fernald, he appears to have selectively used only the “snake pit” portion of Judge Tauro’s statement in referring to Fernald and the other facilities. That, of course, reversed the meaning of Tauro’s disengagement statement.

Deinstitutionalization has not been a uniform success

Judge Tauro believed in the importance of a continuum of care for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities (I/DD), and knew that institutions such as Fernald had an important role to play in it. In his 1993 disengagement order, he maintained that facilities such as Fernald should not be closed unless it was certified that each resident would receive equal or better care elsewhere.

As the years went on, the promise of equal or better care in the community was not realized. Deinstitutionalization has turned out to be fraught with problems for people with I/DD just as it has for people with mental illness. Between 2000 and 2014, the VOR, our national affiliate, catalogued hundreds of cases of abuse and neglect in privatized group homes around the country.

In testimony in 2018 to a legislative committee, Nancy Alterio, executive director of the Massachusetts Disabled Persons Protection Commission (DPPC), stated that abuse and neglect of persons in the Department of Developmental Services (DDS) system had increased 30 percent in the previous five years, and had reached epidemic proportions.

Alterio’s testimony came long after the State of Massachusetts had begun to rely primarily on privatized, community-based group homes for residential care of persons with I/DD, and long after the state had phased out and closed all but two state-run ICFs comparable to Fernald.

Our own analysis of more than 14,000 allegations of abuse made to the DPPC showed that the rates of substantiated abuse and neglect per client in those two remaining ICFs — the Wrentham Developmental Center and the Hogan Regional Center — were practically zero between Fiscal 2010 and 2019.

Yet many advocates for corporate providers, such as the Arc of Massachusetts, have pushed for decades for complete deinstitutionalization and for additional privatization of services for people with I/DD. They have been joined by administrations at the state and national levels, which have continually made state-run care and services targets for closure and outsourcing to contracted providers.

Since 2009, the U.S. Justice Department has filed, joined, or participated in lawsuits around the country to close ICFs regardless of whether the residents or their families or guardians wanted to close the facilities they were living in or not.

Fernald’s opponents have misinterpreted the landmark Olmstead v. L.C. Supreme Court decision

Those advocates of deinstitutionalization and privatization have consistently misinterpreted the 1999 Olmstead v. L.C. U.S. Supreme Court decision, which held that institutional care is appropriate for those who desire it and whose clinicians recommend it.

The late Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg wrote the majority opinion in Olmstead, which has been characterized as holding only that unjustified isolation in institutions is “discrimination based on disability.” But that statement is only half the holding of Olmstead.

There was another major element of Justice Ginsburg’s Olmstead decision that has continued to be disregarded by many who have then gone on to mischaracterize the decision as advocating or requiring the end of institutional care. It didn’t. As the VOR has pointed out, Justice Ginsburg wrote a balanced decision that “supports both the right to an inclusive environment and the right to institutional care, based on the need and desires of the individual.”

Justice Ginsburg’s majority opinion held that:

We emphasize that nothing in the ADA or its implementing regulations condones termination of institutional settings for persons unable to handle or benefit from community settings. . . Nor is there any federal requirement that community-based treatment be imposed on patients who do not desire it.

As Justice Ginsburg stated, community-based care is an appropriate option for those who desire it, whose clinicians support it, and in cases in which states have the resources to reasonably support care in the community system. Unless all three of those conditions hold, institutional care may well be the appropriate setting.

Fernald’s families fought the closure of Fernald from 2003 through 2014

In 2004, the plaintiffs in original Ricci v. Okin consent decree litigation asked Judge Tauro to reopen the case, arguing that the then Romney administration was illegally trying to close Fernald, and was thereby violating the terms of Tauro’s disengagement order. Those plaintiffs included families and guardians of Fernald residents, and members of COFAR and other advocacy organizations.

In February 2006, Tauro appointed then U.S. Attorney Michael Sullivan as Court Monitor in the case and asked Sullivan to review the transfers of 49 residents from Fernald since 2003. Sullivan ultimately recommended to the newly installed Patrick administration that Fernald remain open.

In making the recommendation, Sullivan maintained in his report to Tauro that while the level of care there might be able to be duplicated elsewhere, the loss of familiar surroundings and people “could have devastating effects [on the residents] that unravel years of positive, nonabusive behavior.”

Tauro subsequently ruled that the families at Fernald must be given the option of remaining there. But the Patrick administration ignored Sullivan’s recommendation and appealed Tauro’s ruling to the U.S. First Circuit Court of Appeals. The Circuit Court of Appeals overruled Tauro, without giving deference to his expertise in the case; and the Patrick administration proceeded to phase down and close Fernald and later three other ICFs of the six remaining in the state.

By 2014, the year Fernald was closed, some 14 families were still fighting legal and administrative battles to keep the facility open for their loved ones because they believed the care there was better than in the community-based system.

Those families came in for relentless media criticism and blame from lobbyists for corporate providers, who were seeking to close Fernald and the remaining state-run centers, and to garner the lucrative state contracts that would result from it.

The incestuous nature of the privatized system

The closures of ICFs around the country and the rise of the privatized system of care have provided enormous financial windfalls for politically connected corporate contractors. Their executives have garnered huge increases in their personal compensation, but have frequently neglected to pass through the ever higher levels of state funding to direct-care workers. That is one of the reasons for the epidemic of abuse and neglect in the corporate provider-based system of care.

In 2015, we calculated that more than 600 executives employed by corporate human service providers in Massachusetts received some $100 million per year in salaries and other compensation. By our calculations, state taxpayers were on the hook each year for up to $85 million of that total compensation.

As noted, the line item in the Massachusetts state budget for DDS-funded residential providers has been boosted by hundreds of millions of dollars since Fernald’s closure. Yet, as Massachusetts State Auditor Suzanne Bump’s office reported in 2019, while that boost in state funding resulted in surplus revenues for the providers, those additional revenues led to only minimal increases in wages for direct-care workers.

Administrations mistakenly believe closing ICFs will save money

Much of the justification for, and reasoning behind, closing developmental centers has been based on the fact that providers pay lower wages than do public agencies to direct-care workers. Successive administrations in Massachusetts have also sought to operate the ICFs as inefficiently as possible in order to make them appear as expensive as possible, thereby justifying their closure.

In 2014, the Fernald Working Group, a coalition of local organizations, had recommended a cost-effective approach to care in that setting. Their proposal was that the Fernald Center be downsized and converted to group homes on a portion of the campus while the remainder of the campus was opened to development, open space, and other uses. Similar proposals had been made over the years by the former Fernald League and COFAR.

But the then Romney and subsequent Patrick administrations were interested only in one thing — closing Fernald and three other ICFs in the state, contending the state would save tens of millions of dollars a year in doing so. They never considered any of the proposed alternatives to the closures.

That there isn’t necessarily a long-term fiscal savings in transferring people from developmental centers to decentralized, provider-based care has been acknowledged even by one of the leading proponents of deinstitutionalization in the Obama administration.

In a law journal article, Samuel Bagenstos, a former top litigator in the Justice Department’s Civil Rights Division, acknowledged that any cost savings in closing developmental centers “will shrink as people in the community receive more services.”

He added that a significant part of the cost difference between institutional and provider-based care “reflects differences in the wages paid to workers in institutional and community settings — differences…that states will face increasing pressures to narrow.”

Today, as noted, two ICFs remain in Massachusetts – the Wrentham Developmental Center (WDC) and the Hogan Regional Center in Danvers. We rarely, if ever, hear that families or guardians are unsatisfied with the care there.

Mary Ann Ulevich, a COFAR member and a member of the Wrentham Board of Trustees and of the Wrentham Family Association, wrote to DDS Commissioner Jane Ryder in November 2019 in praise of the care her cousin, Tom Doherty, had received at WDC. Tom had died on October 24 at the age of 68. Ms. Ulevich wrote:

I just want you to know how proud you can be of the work carried out at WDC. I know that the philosophy of care for those with intellectual disability is to provide support to remain in their community with their families, with guidance and services. I fully support this contemporary approach, but acknowledge that there are many who because of their history and challenges, and/or because of the progression of their needs combined with diminished family and community resources, can and do thrive in facility-based care.

Here are additional accounts of the value that families put today on the care at WDC.

Apparently, if we keep blaming Fernald and other congregate-care facilities for all of the dysfunctionality of the DDS system, we will not have to admit that the problems with abuse and neglect and financial mismanagement in the system primarily lie elsewhere.

Setting the record straight about Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s historic contribution to the rights of the disabled

As the nation celebrates the life and judicial legacy of the late U.S. Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, we would like to recognize and set the record straight about her major contribution in one particularly vital case to the rights of persons with cognitive disabilities.

Ginsburg wrote the majority opinion in Olmstead v. L.C., which has been characterized as the most important civil rights decision for people with disabilities in our country’s history. It may have certainly been that, but not, as is usually claimed, because it held that “unjustified isolation (in institutions) is properly regarded as discrimination based on disability.”

That statement is only half the holding of Olmstead. There was another major element of Ginsburg’s Olmstead decision that has continued to be disregarded by many who have then gone on to mischaracterize the decision as advocating or requiring the end of institutional care. It didn’t.

As our national affiliate, the VOR, has pointed out, Ginsburg wrote a balanced decision that “supports both the right to an inclusive environment and the right to institutional care, based on the need and desires of the individual.”

In other words, the greatness of Ginsburg’s contribution to the rights of the disabled was that her decision was all about choice. It provides a choice between community-based care and institutional care to persons with cognitive disabilities.

In announcing the Olmstead decision on June 22, 1999, Ginsburg stated that that the answer was “a qualified yes” to the question whether the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) “…may sometimes require a state to place persons with mental disabilities in community settings rather than in state institutions.”

The key word here was “qualified.” Ginsburg’s majority opinion held:

We emphasize that nothing in the ADA or its implementing regulations condones termination of institutional settings for persons unable to handle or benefit from community settings. . . Nor is there any federal requirement that community-based treatment be imposed on patients who do not desire it.

As Ginsburg stated, community-based care is an appropriate option for those who desire it, whose clinicians support it, and in cases in which states have the resources to reasonably support care in the community system. Unless all three of those conditions hold, institutional care may well be the appropriate setting.

The majority decision included a reference to amicus brief submitted by VOR, which stated that:

Each disabled person is entitled to treatment in the most integrated setting possible for that person – recognizing that, on a case-by-case basis, that setting may be in an institution.

Decision has been misinterpreted

Despite those clear statements, Olmstead has continuously been misinterpreted by policy makers, administrators, and even governmental agencies as requiring the closure of all remaining state-run congregate care facilities in the country and privatizing all remaining residential care. What these advocates have done is to take the choice out of it.

The U.S. Department of Justice’s Civil Rights Division, for instance, has mistitled its technical assistance website, “Olmstead: Community Integration for Everyone.” (my emphasis). That is simply not true. Olmstead clearly implied that community integration isn’t for everyone.

In line with this misinterpretation, the DoJ has for years filed lawsuits around the country to close state-run care facilities, whether the residents and their families and guardians have opposed those closures or not. This has caused “human harm, including death and financial and emotional hardship,” according to information compiled by VOR.

While the DoJ has not filed such a suit against the State of Massachusetts, that may be because the state closed four out of six developmental centers that were in operation in the state as of 2014. Olmstead, however, has been used as a justification in Massachusetts and other states for closing sheltered workshops, as Massachusetts did as of 2016 over the objections of many of the participants and their families.

Those acts and outcomes are not consistent with the plain language of Olmstead regarding the importance of the individual’s personal choice. Nevertheless, facility closure advocates consistently cite Olmstead as justifying their actions.

Community-based care was appropriate for original plaintiffs

The Olmstead lawsuit was brought on behalf of Lois Curtis and Elaine Wilson of Georgia, who both had diagnoses of mental health conditions and intellectual disabilities, according to a website created by attorneys with the Atlanta Legal Aid Society, who represented the women in the case.

Curtis and Wilson had asked the state of Georgia to help them get treatment in the community so that they would not have to live in a mental hospital. According to the Atlanta attorneys, the doctors who treated Curtis and Wilson agreed that they were capable of living in the community with appropriate supports. However, both women had been waiting for years for their community-based supports to be established.

Thus, the original plaintiffs in the Olmstead case satisfied at least two of the three conditions that Ginsburg set for community-based care in the decision: their clinicians deemed community-based care appropriate for them, and they desired it. But Ginsburg recognized that might not be true of everyone in institutional care.

Olmstead wrongly used to justify continuing privatization of DDS services

The Olmstead decision is based on regulations in the ADA that stipulate that public entities should provide services and programs in “the most integrated setting appropriate to the needs” of persons with disabilities.

In Massachusetts, administrations have long contended that the most integrated settings exist in the form of community-based group homes, the majority of which are run by corporate providers that receive state funding.

The problem with this view is that there have been countless examples of group homes that offer residents little opportunity for community integration. Yet the argument that group homes are more integrated than developmental centers is ingrained among policy makers, journalists, and others. This has made it accepted wisdom that all state-run congregate care facilities should be closed — an outcome that will ultimately lead to complete privatization of care.

That appears to be the goal of federal agencies such as the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), which has issued regulations and provided billions of dollars in grants intended to boost the privatized group home system around the country.

On September 23, for instance, CMS announced the availability of up to $165 million in supplemental funding to states currently operating Money Follows the Person (MFP) demonstration programs. As a CMS press release put it, this funding “will help state Medicaid programs jump-start efforts to transition individuals with disabilities and older adults from institutions and nursing facilities to home and community-based settings of their choosing.”

But while this outcome is termed a choice, the closure of the institutions will actually eliminate the choice that Ginsburg articulated in Olmstead. The VOR amicus brief, as noted, stated that on a case-by-case basis, the most integrated setting may be an institution.

The Disability Integration Act of 2019 would further erode Olmstead choice

Unfortunately, the notion that community-based care is the only appropriate option for people with cognitive disabilities is so ingrained and pervasive that the entire Massachusetts congressional delegation signed onto a bill last year, which would encourage further unchecked privatization of human services, diminished oversight, and reduced standards of care across the country.

The bill, known as the federal Disability Integration Act of 2019 (HR.555 and S.117), would potentially threaten the Wrentham Developmental and Hogan Regional centers in Massachusetts, the state’s only two remaining residential facilities for the developmentally disabled that meet federal Intermediate Care Facility (ICF) standards.

The legislation calls explicitly for the the “transition of individuals with all types of disabilities at all ages out of institutions and into the most integrated setting…” (emphasis added). As such, the bill does not comply with the choice provision in Olmstead.

We have contacted the members of the members of the state’s congressional delegation to urge them to support a change in the language of the bill to respect the choice of individuals, families, and guardians either to get into or to remain in congregate care facilities.

Given that the two versions noted above of this bill are still pending in House and Senate committees in Congress, we plan to remind the members of the Massachusetts delegation of the legacy and words of Ruth Bader Ginsburg.

In 1999, Justice Ginsburg endorsed the idea of a continuum of care for the most vulnerable members of our society. Her decision and message were models of inclusivity. Now at the time of her passing, we think it is important to remember and reflect on that.

Direct care workers need more than an official state day and billboards in their honor

Governor Baker and an employee union recently honored home care workers in Massachusetts with an official state day and billboards.

But we think those workers might appreciate better pay and health benefits even more.

Baker and the 1199SEIU health care worker union teamed up to declare “Home Care Day” on September 4. The SEIU also funded the placement of 13 billboards in Boston, Worcester, Springfield, and other cities to highlight minority home care workers.

Tim Foley, vice president of 1199SEIU, told the State House News Service he hoped the billboards will “let home care workers know they are valued by so many families across the commonwealth and push elected leaders to invest in the workforce.”

We agree that the governor and Legislature need to do more to narrow the enormous gap that exists between the wages of direct-care workers and the executive salaries of the primarily private providers that employ them.

In 2018, Baker did sign legislation to raise the minimum wage of direct-care and other workers to $15 an hour; but it won’t reach that amount until 2023. In 2017, the Legislature rejected efforts to raise direct-care wages to $15 as of that year, and rejected a bid last year to raise direct care wages to $20 per hour.

A bill (H.4171) that would similarly raise hourly direct care wages to $20 has been stuck in the Health Care Financing Committee since last November.

Yet, it’s not as if the governor and Legislature are reluctant to provide continually rising levels of funding to the providers themselves. It’s just that the provider executives have chosen not to pass much of that increase through to the direct-care workers. Instead, they have greatly boosted their own personal wealth.

We reported in 2012 that direct-care workers working for corporate providers contracting with the Department of Developmental Services (DDS) had seen their wages stagnate and even decline in previous years while the executives running the corporate agencies were getting double-digit increases in their compensation.

Since 2012, the line item in the state budget for DDS-funded residential providers has increased by nearly 45 percent in inflation-adjusted terms, to over $1.5 billion in Fiscal 2020. That is according to the Massachusetts Budget and Policy Center’s online Budget Browser.

Yet, as State Auditor Suzanne Bump’s office reported last year, while that boost in state funding resulted in surplus revenues for the providers, those additional revenues led to only minimal increases in wages for direct-care workers.

Bump’s May 8, 2019 audit found that the average hourly direct-care wage was $11.92 in Fiscal 2010, and rose only to $14.76 as of Fiscal 2017. That’s an increase of only 24 percent over that eight-year period, an amount that only barely exceeded the yearly inflation rate.

Meanwhile, according to the audit, the increased state funding to the providers enabled them to amass a 237 percent increase in surplus operating revenues (total operating revenues over total operating expenses) during that same eight-year period. The increased state funding was at least partly intended to boost direct-care wages, but it “likely did not have any material effect on improving the financial well-being of these direct-care workers,” Bump’s audit stated.

In 2017, SEIU Local 509 in Massachusetts issued a report similarly asserting that increases in funding to human services providers enabled the providers to earn $51 million in surplus revenues. The union contended that the providers could and should have used the surplus revenues to boost direct-care wages.

Confirming our 2012 findings, the SEIU’s 2017 report stated that during the previous six years, the providers it surveyed paid out a total of $2.4 million in CEO raises. The SEIU report concluded that:

This all suggests that the amount of state funding is not at issue in the failure to pay a living wage to direct care staff, but rather, that the root of the problem is the manner in which the providers have chosen to spend their increased revenues absent specific conditions attached to the funding. (my emphasis)

So, as noted, it isn’t a matter of the providers not having the money. The governor and Legislature need to pass a bill such as H.4171, which would require providers to use up to 75 percent of their total state funding to boost direct-care worker salaries to at least $20 per hour.

In other words, if state-funded providers aren’t willing to pay a living wage to the workers they employ, then it’s time for the state to step in and require them to do so. If that were to happen, Governor Baker would have put some substance behind a declaration of a Direct-Care Worker Day in Massachusetts.

Why the media won’t cover issues of concern to people with developmental disabilities

Whether it’s due to “cancel culture” or a misguided ideology that the largely privatized system of care in society is functioning perfectly for people with intellectual and other developmental disabilities, the mainstream media these days just don’t seem interested in reporting about the system.

For a while now, we’ve been debating why it is so difficult to get media coverage in Massachusetts, in particular, of issues of concern to this group of people and their families and guardians.

A letter sent to the New York Times may provide one answer. In the August 20 letter, 75 organizations and leaders in the disability community critique that newspaper’s apparent lack of interest in covering “serious issues facing those with significant intellectual and developmental disabilities.”

The Times has apparently not yet published the letter, which is sponsored by the nonprofit National Council on Severe Autism (NCSA).

The letter points out that the Times, while recently honoring the 30th anniversary of the signing of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), failed to include virtually any mention of persons with intellectual or other developmental disabilities. Yet the paper published over two dozen articles over the past few weeks about people with a wide range of other, non-cognitive disabilities.

As the NCSA’s letter to the Times notes, “the full story” in honoring the ADA would include those people with profound intellectual and developmental disabilities. But in doing so, the Times would have to acknowledge that this group of people do not have “the autonomous decision-making, independent living, and competitive, minimum-wage employment that are the cornerstones of the Disability Rights movement.”

The letter ties the Times’ disregard of the developmentally disabled to “cancel culture.” The letter states:

It is ironic that the Times has excluded the most disabled from its ADA coverage exactly as a debate about “cancel culture” has embroiled this newspaper and others. Severe intellectual and developmental disability should be a bipartisan issue — we, the undersigned, represent the broad range of the political spectrum. But because our stories don’t fit the progressive left’s disability narrative, they have been effectively cancelled — exactly by those who claim to care most about this vulnerable population.

We think the disregard of the developmentally disabled is evident in the mainstream media as a whole. The media buy into an ideology promoted by much of the disability advocacy community that no one, no matter how low their measured cognitive functioning may be, has limits on what they can achieve in the community system.

The problem is that this is an absurd position, and it leads to basic contradictions between the ideology and reality. People with intellectual disabilities do have limits on their ability to function in society. Rather than confront that contradiction, the media appear to have chosen to ignore people with cognitive disabilities altogether.

When we raise issues about the need for institutional care or sheltered workshops for those with intellectual disabilities, the media in Massachusetts don’t want to hear about it. It doesn’t fit the narrative that there is no one who is incapable of functioning perfectly in the community and working in mainstream jobs.

We recently reported that the Baker administration discussed reducing public reporting of data on testing of individuals and staff in DDS-funded group homes for COVID-19. Although we tried to bring our concerns over that issue to the attention of the mainstream media in Massachusetts, no media outlet has run any articles about it.

With only the occasional exception, the mainstream media in Massachusetts do no more than scattershot reporting even on the tragic and ongoing problem of abuse and neglect in the DDS system.

Community-first ideology pushed by successive administrations and corporate providers

Perhaps not coincidentally, the ideological position that the community system of care is working perfectly for everyone fits with a decades-long push by successive administrations in Massachusetts and corporate providers for more privatization of the DDS system. According to the ideology, clients in privatized, community-based residences are completely integrated with their communities and can reach their full potential there, unlimited by institutional constraints.

But while the community-based system has meant more state-funded contracts for providers and skyrocketing pay for its corporate executives, the system has largely failed to integrate its clients, and is beset by a bottom-line mentality that provides low pay, training, and supervision of direct-care staff.

Systematic reporting on inadequacies in care in the privatized system, or on a lack of adequate testing in that system for COVID-19, is not desired by corporate, state-funded providers.

Absurd position that autism is “perfect”

The letter to the Times pointedly criticizes an essay that the newspaper published in July that illustrates the ideology driving media coverage today. The essay by writer Madeleine Ryan, the mother of an autistic child, is titled “Dear Parents: Your Child with Autism is Perfect.”

In it, Ryan stated, “Your child might be verbal, nonverbal, aggressive, passive, introverted or extroverted. It doesn’t matter.” She added, “Your child is perfect. Be skeptical of what doctors, teachers, family members or friends say to the contrary.”

The letter to the Times includes a response to Ryan’s piece by Amy Lutz, founding board member of the NCSA and parent of a severely autistic son:

[Jonah] will never go to college, hold a job, see the world, or have a romantic relationship. He will always require round-the-clock supervision, because he has no safety awareness: he doesn’t look before crossing the street, despite years of instruction; and in one terrifying moment, he tried to jump off a cruise ship because he wanted to swim in the ocean… Jonah’s experience is just as important…and must not be elided from the narrative in favor of some kind of fantasy autism nirvana.

The letter further quotes Lee Elizabeth Wachtel, Medical Director of the Neurobehavioral Unit at the Kennedy Krieger Institute and an Associate Professor of Psychiatry at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine:

When an autistic child has permanently blinded himself from self-injury, broken his teacher’s arm, or swallowed multiple toothbrushes and required emergency surgery, there is nothing perfect or magnificent about it, and it must be remedied.

Warning in the Olmstead decision

The letter to the Times notes a warning by Justice Anthony Kennedy in the Olmstead v. L.C. U.S. Supreme Court decision, which cleared the way for expanded privatization of care of the developmentally disabled. In a concurring opinion to the Olmstead decision, Kennedy wrote that:

It would be unreasonable, it would be a tragic event, then, were the (ADA) to be interpreted so that States had some incentive…to drive those in need of medical care and treatment out of appropriate (institutional) care and into settings with too little assistance and supervision.

Unfortunately, that is exactly what the ADA and the Olmstead decision itself have been interpreted by the media and many advocates as allowing.

Both the ADA and Olmstead are being used as covers for the real attitude toward the developmentally disabled on the part of the media and so many others in positions of power — they just don’t care.

After long fight by advocates for Nicky’s Law, key state lawmakers seek postponement of its effective date

The chairs of a key state legislative committee are seeking a nearly year-long delay in establishing a long-sought registry of staff found to have abused persons with developmental disabilities in Massachusetts.

The delay would postpone the effective date of Nicky’s Law from January to November of next year, leading to objections from COFAR and other advocacy organizations that have fought for implementation of the legislation.

State Representative Kay Khan and Senator Sonia Chang-Diaz, the House and Senate chairs of the Children, Families, and Persons with Disabilities Committee, are both reportedly seeking the delay in implementation of the law at the request of the Disabled Persons Protection Commission (DPPC).

The DPPC, the state agency charged with investigating abuse and neglect of disabled adults, was put in charge of developing the registry under the new law.

A staff member for Khan declined yesterday to say why the DPPC, along with Khan and Chang-Diaz, are seeking the delay. “We appreciate your concern and are having further conversations,” the staff member wrote in an email in response to COFAR’s query.

On February 13, 2020, Governor Baker signed the bill into law. The legislation establishes a registry of names of employees of the Department of Developmental Services (DDS) and its providers who have been found by the DPPC to have committed acts of substantiated abuse resulting in serious physical or emotional injury.

Currently, persons applying for caregiver positions in the DDS system must undergo criminal background checks, which disclose previous convictions for abuse and other crimes in Massachusetts and other states. However, even when abuse against persons with developmental disabilities is substantiated by agencies such as the DPPC), it does not usually result in criminal charges. As a result, those findings of substantiated abuse are often not made known to providers or other agencies seeking to hire caregivers.

We have long maintained that these problems have gotten steadily worse as functions and services for the developmentally disabled have been steadily privatized over the years without sufficient oversight of the corporate provider-based system.

Last year, we analyzed DPPC data on a per-client basis of more than 14,000 abuse complaints in the Fiscal 2010-2019 period. That analysis underscored the relative dangers of privately provided, but publicly funded care. We have reported over the years on abuse and poor care are problems that involve providers throughout the system.

An abuse registry is needed as soon as possible in Massachusetts. At the same time, we think this registry is only a start. Ultimately, the executives of the provider agencies need to be held accountable for the bottom-line mentality in many of their organizations that fails to provide resources for training and supervision of direct caregivers.

We are asking people to call the offices of the Senate and House chairs Children and Families Committee at (617) 722-1673 and (617) 722-2011 respectively, or email Senator Change-Diaz at Sonia.Chang-Diaz@masenate.gov or Rep. Khan at Kay.Khan@mahouse.gov. Please ask them for a justification of their plan to delay the implementation of Nicky’s Law.

ACLU and SEIU surprisingly and confusingly gang up on congregate care for the developmentally disabled during COVID crisis

The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) and the Service Employees International Union (SEIU) are usually strong advocates of accountability and transparency in government.

That’s why it is surprising that both of those organizations appear to be using the coronavirus pandemic to further a longstanding agenda, which we never knew they shared, to privatize services to people with intellectual and developmental disabilities.

It’s particularly surprising that the SEIU, a human services employee union that represents caregivers in the state’s two remaining developmental centers, would be on board with closing down state-run care facilities.

In a petition filed June 23 with the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), the ACLU, SEIU, and a number of other advocacy organizations appear to start off on the right track in criticizing the federal government for its mismanaged response to the pandemic.

The petition identifies nursing homes, Intermediate Care Facilities for the developmentally disabled (ICFs), and group homes as sites of large numbers of COVID-19 infections and deaths that could have been prevented with better guidance for infection control, more testing, and better patient and worker protections.

But the petition then goes on to make a number of, at times, poorly conceived and even confusing claims and recommendations that ultimately appear intended to support a privatized care agenda.

At least some of the confusion centers around group homes, which the petition lumps together with ICFs as sources of “congregate care.”

The petition suggests that among the causes of the infections and deaths is the federal government’s failure “to divert people from entering nursing homes or other congregate settings” or to increase discharges from those settings “to the community.”

The argument the petition makes is that reducing the population in all of those facilities would “make social distancing possible.”

The petition defines congregate settings as including ICFs, psychiatric facilities, and group homes. Yet, group homes are considered part of the community-based system of care in Massachusetts and other states. As a result, it isn’t clear what the ACLU and SEIU mean in stating that people living in group homes would be among those in congregate settings who should move “to the community.”

The petition, moreover, calls for reducing the population of nursing homes and congregate settings by 50 percent. Should HHS neglect to act within three weeks to enact that and other suggested measures, the groups will sue, the petition states.

It is unclear whether the ACLU and SEIU mean that nursing homes, ICFs, and group homes should all be emptied of 50 percent of their residents, or where those residents would then go.

VOR, COFAR’s national affiliate, issued a statement sharply critical of the petition, maintaining that:

…the ACLU has cast its net too wide, and falsely claimed to represent the interests of everyone receiving federally funded services who is classified as elderly or who has intellectual and developmental disabilities. In doing so, it apparently assumes that all such persons look and feel alike and need the same supports and level of care.

Further confusion over the HCBS waiver

Adding to the confusion over group homes is language in the ACLU/SEIU petition calling on HHS to “provide incentives to states to redesign their Medicaid programs to expand Home and Community Based Services (HCBS) and other community-based services and supports” with the goal of the 50 percent reduction in the population in congregate settings.

Once again, that language is confusing in that group homes in Massachusetts and other states have long been recipients of federal funding under an HCBS waiver of Medicaid regulations governing ICFs. In asking for an expansion of Medicaid funding under the HCBS waiver, is the petition suggesting that the money go toward care in a setting other than group homes?

ACLU/SEIU petition misreads the Olmstead Supreme Court decision

The ACLU/SEIU petition further misreads the landmark Olmstead v. L.C. U.S. Supreme Court decision, which paved the way for expansion of privatized care. Although the 1999 decision held that community-based care should be made available for those who desire it, it nevertheless recognized the role played by institutional care for those who can’t function under community-based care.

The Olmstead ruling stated that the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) “does not condone or require removing individuals from institutional settings when they are unable to benefit from, or do not desire, a community-based setting.”

We have asked the SEIU’s Massachusetts affiliate, Local 509, whether it is in support of the ACLU/SEIU petition. We have not heard back yet, but we hope they are in a position to disavow it.

There is a lot to be concerned about regarding the efforts of both the federal government and the state government here in Massachusetts to protect persons with intellectual and developmental disabilities from the virus. We’ve raised a lot of those concerns over the past few months.

At the same time, and for that reason, we don’t think it is appropriate for any organization to use the pandemic to support an anti-institutional agenda.

Administration withholding information on COVID-19 conditions in DDS system

Even as the Baker administration reports daily on COVID-19 infection rates among most of the population in Massachusetts, numbers of infected persons with intellectual and developmental disabilities appear to be being kept under wraps.

Information is coming out sporadically and anecdotally from the media and individuals on the ground.

The Boston Globe and other outlets reported this week that as of Tuesday, 276 people in Department of Developmental Services (DDS) residential settings statewide had tested positive as had 321 staff. Nine people receiving services from DDS had died from COVID-19.

Among the anecdotal information we’re getting:

- While testing was completed last Sunday of residents at the Wrentham and Hogan Developmental Centers, the staff at Wrentham apparently did not get tested, as the administration had reported. DDS Commissioner Jane Ryder said late yesterday that testing of the Wrentham staff will now take place this weekend.

- WCVB reported yesterday (April 17) that 40% of residents in three units at the Hogan Center had tested positive for the virus, according to the Massachusetts Nurses Association. The union said that 44 residents and 55 staff members have also tested positive.

While the Department of Public Health (DPH) provides daily updates on deaths and infections due to COVID-19 throughout the state, information has only been provided sporadically by the administration, and on a selective basis to the media, about the situation in the DDS system.

The number of deaths and COVID-19 positive cases in the DDS system appears to be rarely if ever mentioned in press briefings held by Governor Charlie Baker and Health and Human Services Secretary Marylou Sudders.

This raises a question whether the administration is placing a lower priority on protecting the DDS population from the virus than it is placing on other long-term care populations such as the elderly and even chronically ill.

Joe Corrigan, a COFAR member and member of the Wrentham Center Board, expressed his frustration in an email yesterday to Sudders and and DDS Commissioner Jane Ryder. He wrote,

Tell us where the decisions are being made. Tell us what the tipping point is for getting real and complete attention to (the Wrentham Developmental Center) and all DDS. Tell us where our loved ones stand in the pecking order vs. the poor souls at soldiers homes, nursing homes.

COFAR has requested information on numerous occasions on testing results in the DDS system from Sudders and Ryder, and has gotten only limited answers and often no response. We were forced on Thursday to file a Public Records Law request with EOHHS, DDS, and DPH for records on the timeline for testing in the DDS and DPH systems.

Staff not tested at Wrentham Center

As we reported on Wednesday, the administration has engaged Fallon Ambulance Service, a private company, to carry out the testing throughout the DDS group home system and apparently in the state-run developmental centers.

However, contrary to reports from the administration, testing of staff has apparently still has not occurred at the Wrentham Center. The administration had reported that all residents and staff in the Hogan and Wrentham Centers had been tested last Sunday.

Earlier this week, a Wrentham staff member told COFAR Executive Director Colleen M. Lutkevich that, “at this time only the residents (at Wrentham) were tested.” The staff member added in an email that direct care staff were “doing a wonderful job of taking care of the residents at this time, but the reality is they are also the ones that will be bringing the virus in. There have been several residents that have tested positive, but there still has not been any testing of the staff.”

Yesterday, a DDS official told Lutkevich that Fallon Ambulance said they “would work with us to come back to Wrentham to test the staff there,” but that he had “no specifics on when they may schedule us.” Late yesterday, however, Ryder informed Lutkevich that the testing would take place this weekend.

In his email to Sudders and Ryder, Corrigan pointed to the continued lack of testing of staff at the Wrentham Center as a critical problem:

I have no doubt that (administrators and staff at the Wrentham Center) are doing much with little in terms of distancing, etc. but please tell me what is the sense of testing residents without testing the staff who come and go daily and have to be the ones who brought in the virus to the already affected and, no doubt, growing number of victims.

Crisis highlights problem with privatized care

The testing problems are potentially compounded in the DDS group home system. Some 8,800 residents are dispersed around the state in more than 2,000 group homes, most of which are operated by corporate nonprofit providers to DDS. We are estimating that there are some 14,000 to 15,000 direct-care staff serving those residents. All of those people have become potential or actual targets of the virus.

No information has so far been forthcoming from the administration on how long the Fallon testing program will take in the group homes. Fallon is reportedly capable of testing between 500 and 1,000 individuals per day. We are already hearing anecdotal reports about delays in scheduled testing by Fallon in some group homes.

Fallon is facing the prospect of having to test at least 22,000 residents and staff in the residences. That apparently doesn’t count the clinicians, physical and occupational therapists, nurses and others who may still be visiting those homes and might not be there when the testing is being done in a particular home. We also have no information on testing plans for staff that is not working the shifts at the time of the mobile testers are there.

Group home model presents logistical problems

The COVID-19 crisis appears to show how potentially poorly the privatized care model is at protecting people during pandemics. DDS was reportedly able to test all residents and staff in the state run developmental centers in one day, with the apparent exception, however, of staff at the Wrentham Center.

Due to the highly decentralized nature of the privatized group home system, it is probably impossible to do the necessary testing within a relatively short time frame unless the administration was to call in the National Guard or another source of large-scale assistance. This raises the question whether the administration considered that, and if so, why they rejected it with respect to the DDS system, but have adopted it for the DPH nursing homes.

It further appears that within the privatized community-based system, highly compensated executives should have been doing strategic planning for the potential occurrence of a pandemic such as this one, and apparently did not do that planning.

A single testing site for group homes might make more sense

COFAR President Thomas Frain suggested that given the wide dispersal of group homes around the state, it might make more sense to test all group home residents at one site such as Gillette Stadium in Foxborough.

Frain suggested that if testing at a site such as Gillette were made available and each group home took just one resident per day to the site for testing, all residents and direct-care staff could potentially be tested in as little as 10 days. That is based on Frain’s calculation that there are some 2,500 group homes in total, containing some 25,000 residents and staff.

“Instead of ambulances traversing the commonwealth, they could have put all of those ambulance people at a single testing site swabbing people,” Frain said. Some people who could not be transported, would have to be tested at their residences, and Fallon could do that.

In the final analysis, we think a quote from the late U.S. District Court Judge Joseph L. Tauro is unfortunately highly relevant to the situation today. Judge Tauro wrote:

The (intellectually disabled) have no potent political constituency. They must rely on the good will of those of us more fortunate than they, and the constitution…

Resident of group home was sickened by an inappropriate anti-psychotic medication as prescription was increased by 500%

A group home administered an inappropriate and unnecessary anti-psychotic drug to an intellectually disabled woman and increased the dosage by 500 percent last year, according to the woman’s sister.

The 57-year-old woman, who we are referring to as C.J. for privacy reasons, developed tardive dyskinesia after being administered the anti-psychotic drug, Latuda, for nine months, according to her sister, Ellen O’Keefe, who is also an advocate for her.

The staff of the Canton-based group home also left the woman alone on two occasions last June and in January of this year in apparent violation of regulations of the Department of Developmental Services (DDS). The group home is operated by Delta Projects, Inc., a corporate provider to DDS.

In one instance, C.J. was admitted to a hospital for treatment of pneumonia after she was left alone by the staff in the residence, O’Keefe said. She was later admitted to the same hospital for treatment of symptoms of the tardive dyskinesia, her sister said.

Tardive dyskinesia is a serious disorder that caused further cognitive impairment in C.J. and involuntary, repetitive body movements, O’Keefe said. She said her sister has also begun to need a walker. O’Keefe, at COFAR’s suggestion, reported the use of the medication on C.J. to the Disabled Persons Protection Commission (DPPC).

O’Keefe said C.J., who has moderate intellectual disability, can’t read, but has very good communication skills.

Last week, O’Keefe and her family moved C.J. to a new group home run by a different provider, South Shore Support Services. O’Keefe said she was not offered an option by DDS of placing C.J. either in a state-run group home or a residence closer to her family; but the family accepted the placement DDS offered because they wanted C.J. removed from Delta Projects’ care as soon as possible.

C.J. had lived for about four years in the Delta Projects group home. The increasing dosages of Latuda were prescribed by Carine Luxama, a nurse practitioner with Nova Psychiatric Services in Quincy, a subcontractor to Delta Projects.

Ellen O’Keefe (left) and C.J. C.J.’s apparently inappropriate placement on an anti-psychotic medication in her group home last year apparently resulted in tardive dyskinesia, a serious side effect.

According to records in the case, Luxama first prescribed a dosage for C.J. of 20 mg per day of Latuda in March 2019, and then periodically upped that dosage to 120 mg by November. In December, at O’Keefe’s insistence and that of another of C.J.’s sisters (who has asked to be referred to by her first name, Nancy), Luxama agreed to discontinue the medication.

Luxama, who I reached last Wednesday (February 26), declined comment on her role in prescribing the Latuda medication for C.J., saying she is prevented from discussing the matter due to patient confidentiality.

According to Wikipedia, Latuda is used to treat schizophrenia and bipolar disorder — mental impairments that can produce delusions, hallucinations, and extreme mood swings. In addition to tardive dyskinesia, serious side effects of Latuda may include neuroleptic malignant syndrome, a potentially life-threatening reaction; an increased risk of suicide, and high blood sugar levels.

Newsweek magazine reported in 2015 on a study in the British Medical Journal showing that anti-psychotic medications were being “grossly over-prescribed” to people with intellectual disabilities. In the study of 9,135 people, 71 percent “did not have the kind of serious mental illnesses the drugs were designed to treat.”

“All along, we had no idea that Latuda was in fact an anti-psychotic medication,” O’Keefe said. “We believed it was in the same class of anti-depressant medications she had always been prescribed by her previous psychiatrists.”

In 2015, O’Keefe signed a health care proxy statement on C.J.’s behalf, which gave her the authority to make all health care decisions for C.J. and “to give consent to any medical procedures, including treatment with anti-psychotic medication.” However, O’Keefe said that she never gave informed consent to the Latuda that C.J. was placed on, or to its increased dosages.

I have received no response to emails I sent seeking comment on the case to several Delta Projects staff on February 20 and February 25, including to John Pallies, Delta Projects president and CEO.

Family disputes diagnosis of delusions

In her “psych medication” case notes, Luxama wrote on November 1 — some seven months after first prescribing the Latuda — that C.J. was experiencing hallucinations and delusions, and was “having conversations with people no one sees.”

However, O’Keefe strongly disputed that C.J. has ever been delusional, and said she had never previously been diagnosed as psychotic. She said C.J. frequently engages in “self talk,” a coping mechanism for many people with intellectual disabilities. Her self-talk, O’Keefe said, has sometimes been misinterpreted by group home staff as delusional behavior.

O’Keefe said C.J.’s mood swings have largely been the result of her unhappiness with the lack of work activities offered in her day program in recent years. (COFAR has reported that many former participants of DDS sheltered workshops have continued to experience a lack of work opportunities after the workshops were shut down by the state as of 2016.)

In 2014, C.J.’s then long-standing primary care doctor at Brigham & Women’s Hospital described her as suffering from “generalized anxiety disorder” and panic attacks resulting from “being far from her family, worrying about her mother’s health, and not having access to a peer group with whom she can interact and be active.” Anxiety disorder and panic attacks do not necessarily involve delusions or other forms of psychosis.

In her case notes prior to November 1, Luxama did not mention any psychotic or delusional behavior on C.J.’s part. In her notes dated March 25, when she first prescribed Latuda, Luxama wrote only that she was prescribing it for “mood swings.”

While anti-psychotic medications are sometimes used to treat non-psychotic anxiety disorder, at least one psychiatric study warned that:

…the side effect burden of some atypical anti-psychotics probably outweighs their benefits for most patients with anxiety disorders. The evidence to date does not warrant the use of atypical anti-psychotics as first-line monotherapy or as first- or second-line adjunctive therapy in the treatment of anxiety disorders.

Latuda falls into the class of what are known as “atypical” or “second-generation” anti-psychotics. The study added that:

…some patients with highly refractory anxiety disorders may benefit from the judicious and carefully monitored use of adjunctive atypical anti-psychotics. A careful risk-benefit assessment must be undertaken by the physician, on a case-by-case basis, with appropriate informed consent.

However, O’Keefe said she and Nancy, who is also an advocate for C.J., didn’t know that Latuda was an anti-psychotic medication until O’Keefe received a notice in December from Medicare stating that C.J. had been approved in November for another drug, Ingrezza. That sparked her curiosity, she said, and she looked up Ingrezza and found out it is used to treat tardive dyskinesia. Tardive dyskinesia is known to be caused by anti-psychotic medications.

O’Keefe said Luxama also did not disclose that C.J. was being treated with Ingrezza for tardive dyskinesia, and the group home staff did not respond when O’Keefe asked about the Ingrezza on three occasions in early December.

O’Keefe believes the continually increasing dosages of Latuda caused the tardive dyskinesia disorder, which was exacerbated by a final 50 percent increase in the dosage from 80 mg to 120 mg in mid-November. She said that last increase was not disclosed to her family by the group home until almost a month after the fact.

Left alone twice

During the period in which C.J. was losing cognitive functioning, she was left alone twice by the staff in her group home. In the first of those instances in June, she had pneumonia and was admitted to a hospital for treatment after a visiting nurse not associated with Delta Projects found her seriously ill on a couch in the residence.

C.J. was left alone in the residence for a second time in late January.

DDS Commissioner says leaving C.J. alone was “not acceptable”

O’Keefe reported the first incident in which C.J. was left alone in the group home to DPPC, and reported the second incident directly to DDS Commissioner Jane Ryder. O’Keefe cc’d COFAR in her January 31 email.

In a February 7 email in response to O’Keefe and to COFAR, Ryder maintained that “leaving an individual home alone is absolutely not acceptable and DDS has taken immediate and appropriate action.”

Ryder said staff at Delta Projects “have been terminated as a result…and DDS has increased oversight and monitoring of the Delta residences.” She added that DPPC was contacted “and a thorough investigation of the matter will be conducted.”

Ryder did not respond to an email I sent to her on February 20, asking for comment about the medication issue.

C.J. on a family outing.

Inappropriate placement on anti-psychotic medication

O’Keefe told COFAR she was surprised to find out in December that C.J. had been placed on an anti-psychotic medication because C.J. is not psychotic and was not diagnosed as such by two other psychiatrists who have cared for her in the past. She said she was never prescribed that class of medication before.

On December 7, 10, and 20, O’Keefe sent three separate emails to Kelley Hegarty, director of residential supports at Delta Projects, asking why C.J. was prescribed a medication that was causing her to have symptoms of tardive dyskinesia. She said Hegarty didn’t respond to any of her emails.

On December 20, after first learning at C.J.’s annual physical that Luxama had raised her prescribed dosage of Latuda to 120 mg from 80 mg, Nancy emailed Luxama, saying that at that physical, she noticed that C.J.’s “whole demeanor, body language, and ability to communicate were greatly impaired.”

“Who ordered this drastic change (in medication), when, and why?” Nancy asked in the email. According to Nancy, C.J. was exhibiting “multiple, troubling side effects” such as rigidity, hand shaking, psychomotor impairment, loss of balance, stiffness of arms and legs, dark colored urine, and flat affect in her face.”

Nancy asked that all of C.J.’s medications be reviewed and that “serious consideration be given to lowering the dosage of Latuda with a goal of slowly tapering her off this medication and eliminating the known side effects that this drug causes.”

Some two weeks after Ellen began inquiring about the Latuda and its apparent side effects, Nancy finally received a response on December 20 from Hegarty of Delta Projects. Luxama was out of the office that week, but Hegarty said she had been able to reach her and that Luxama had “agreed” to decrease C.J.’s dosage of Latuda from 120 mg to 60 mg per day.

On December 27, Tori Petti, Delta Projects residential manager, provided O’Keefe with a timeline of C.J.’s Latuda dosages. O’Keefe said she and Nancy had insisted on the timeline after discovering that the dosage had been increased from 80 mg to 120 mg without their knowledge.

O’Keefe said the last increase in the dosage of Latuda resulted in a two-week stay for C.J. in January at Milton Hospital where she needed physical and occupational therapy related to her tardive dyskinesia symptoms.

According to Petti’s timeline, Luxama first prescribed a dosage of 20 mg per day of Latuda starting on March 25, and raised that dosage on May 6 to 60 mg because C.J. was “appearing ‘more disorganized and paranoid.”

Then on November 1, Luxama increased the prescribed dosage of Latuda to 80 mg and then to 120 mg on November 14, “due to increased anxiety, mood swings, irritability, paranoia, delusions, and aggressive panic attacks,” according to Petti’s timeline.

O’Keefe, however, later challenged those assessments of C.J.’s behavior, stating in a January 14 email to Luxama that “no reasonable examples of this behavior were cited in your notes.”

The real problem, O’Keefe maintains, was that C.J. was experiencing negative side effects of increasing dosages of an inappropriate medication. “The Latuda was causing an alarming decrease in her cognitive awareness and physical endurance,” O’Keefe said. “She became more docile and passive so Delta staff could handle her more easily and suppress her independence.”

O’Keefe said that on December 27 and January 3, she sent emails to Luxama, seeking her rationale for the final increase in the Latuda dosage to 120 mg. She said she got no response until January 7, when Luxama emailed her and seemed to place responsibility on the Delta Projects staff for not having informed O’Keefe and Nancy of the November dosage increase.

“Being new to (C.J.)’s care team, it was my understanding that (Delta) staff would be communicating the outcome of appointments with all involved parties, and that I would be available to answer any questions or concerns anyone might have,” Luxama stated in the January 7 email.

But while Luxama said she would be available to answer questions and concerns, O’Keefe said Luxama didn’t respond to her follow-up email with further questions on January 14.

In that January 14 email to Luxama, O’Keefe said she and Nancy believed Luxama was relying on assessments of C.J’s mental state by non-clinical staff in her group home and day program. O’Keefe said that C.J. was “very unhappy” because her day program had “practically stopped offering her enclave work (and) there is nothing ‘meaningful’ for her to do.” C.J.’s mood, Ellen told COFAR, “was largely the result of her environment, not because she had mental illness.”

Referring to Luxama’s alleged reliance on the group home and day program staff assessments in prescribing the Latuda, O’Keefe’s January 14 email added:

The individuals who support (C.J.) day-to-day and made these ‘clinical type of evaluations’ about her behavior do not truly understand the repercussions in their ‘choice’ of words they used in describing (C.J.), and in our opinion this is a very dangerous practice. Why didn’t you ever elicit our input? When we started this relationship, you agreed to a team approach – including input from Nancy and I who are also her advocates.

Meanwhile, Luxama’s agreement to reduce the Latuda dosage in December apparently did not result in a reduction in C.J.’s symptoms of tardive dyskinesia, at least in the short term.

On January 8, C.J. was taken by ambulance to Milton hospital for testing, according to an email to O’Keefe and Nancy from Petti. “We believe there is a neurological issue with C.J. as her cognitive abilities continue to decline,” Petti’s email added.

In her January 14 email to Luxama, O’Keefe stated that When C.J. was admitted to Milton Hospital, “the emergency doctor noted she was ‘highly medicated’ and inquired about the anti-psychotics she was taking as her cognitive ability was so impaired.” O’Keefe added in her email that the ER doctor “also noted she (C.J.) had trouble moving her jaw and couldn’t speak. Are you aware that she has had accidents due to incontinence now? We have since learned that this is also one of the adverse side effects of Latuda.”