Archive

Unspecified ‘settlement agreements’ allow abusive care providers to avoid placement in state Registry

[Clarification: This post has been updated to note that the settlement agreements referred to in the post were reached between the Disabled Persons Protection Commission and care providers who had filed appeals to the state Division of Administrative Law Appeals of registrable abuse affirmations.]

———————————————————————————————————————————————–

State data show that in more than 40% of the cases in which care providers of persons with intellectual and developmental disabilities (I/DD) appealed “registrable abuse” affirmations to a state adjudicatory body, the state entered into “settlement agreements” with those providers.

Each of those settlement agreements, which are not subject to public disclosure, enabled the care providers to avoid placement in the state’s Abuser Registry.

Meanwhile, with that data also showing that a majority of abusive care providers of clients with disabilities have been able to avoid placement in the three-year-old Registry, we are asking the co-sponsors of the Registry statute to support corrective language to that statute and regulations.

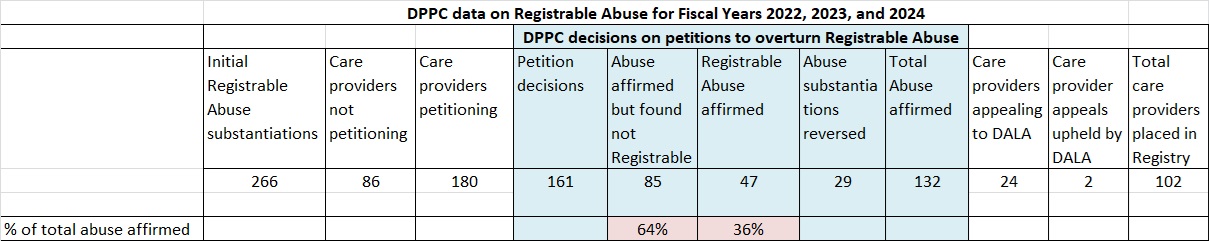

The data, provided to COFAR by the Disabled Persons Protection Commission (DPPC), show the outcomes of the first three years of the operation of the Registry, which was established under “Nicky’s Law” in 2020. The DPPC data cover a period since the database was first put into use in July 2021.

Nicky’s Law was enacted to ensure that care providers who have been found to have committed abuse or neglect are no longer able to work for the Department of Developmental Services (DDS) or for any agency funded by DDS.

We first reported in July that in only about a third of the cases in which the DPPC or DDS affirmed initial substantiations of abuse allegations against care providers did the DPPC conclude after appeals that those persons’ names should be placed in the Registry.

Care providers against whom either the DPPC or DDS have substantiated allegations of registrable abuse have two avenues of appeal under the Registry law and regulations. First, a care providers can directly petition the DPPC to either overturn the substantiation or determine that the the abuse was not “registrable.”

Second, if the DPPC denies the care provider’s appeal, the care provider can further appeal to the Division of Administrative Law Appeals (DALA), an independent state agency that conducts adjudicatory hearings.

A detailed set of DPPC data, which we received in October, show that from Fiscal Years 2022 through 2024, care providers who petitioned the DPPC had their registrable abuse findings reduced to non-registrable abuse in 65% of the cases in which the DPPC had nevertheless affirmed, after the appeals, that abuse had occurred. That meant those care providers’ names would not be placed in the Registry.

Further, care providers who lost their DPPC appeals and then exercised their right to appeal again — this time to DALA — were able to avoid placement in the Registry in 43% of those DALA appeals. Thus, out of 192 care providers who petitioned and appealed both to the DPPC and then to DALA, only 7 care providers were subsequently placed in the Registry — a placement rate of only 4% of those petitioning and appealing to both the DPPC and DALA.

A total of 122 care providers were either placed in the Registry (119) or had their placements pending (3) during the three-year period. That number includes the 7 care providers who lost both sets of appeals to the DPPC and DALA, and 115 care providers who either didn’t file any appeals or who didn’t appeal to DALA.

A total of 283 care providers were initially found by either DPPC or DDS investigators to have committed substantiated abuse. So, the placement of 122 of those care providers in the Registry is a placement rate of 43%. The placement percentage is only that high because so many care providers didn’t exercise any or all of their appeal rights.

The chart below summarizes this data. (Click to enlarge.)

Also, while a DPPC attorney had previously said that the DPPC has had a policy of placing all care providers in the Registry who were found liable for sexual abuse, the data show that in 8 instances in which those care providers petitioned the DPPC, the abuse allegations were changed from registrable to non-registrable.

The settlement agreements

According to the DPPC data, 28 care providers, who lost their petitions to the DPPC, subsequently appealed to DALA during the three-year period. Of those 28 appeals, DALA, as noted, denied only 7, clearing the way for the placement of those care providers in the Registry. DALA reversed 2 of the appealed cases from substantiated to unsubstantiated abuse.

In an additional 12 cases, the DPPC entered into unspecified “settlement agreements with care providers who had filed appeals to DALA of registrable abuse affirmations. Seven appeals remained pending.

Each of those 12 settlement agreements allowed the care provider to avoid a Registry placement. According to the DPPC, the settlement agreements “generally involve the modification of the finding of ‘registrable abuse’ to (non-registrable) ‘abuse’ upon verification that the care provider underwent corrective action, such as remedial training.” In each of the settlement agreements the appeal to DALA was subsequently withdrawn.

A DPPC attorney stated that the settlement agreements are not public records.

We have asked the DPPC for clarification as to whether potential settlement agreements are offered by the DPPC to all care providers who file appeals to DALA of registrable abuse affirmations. If not, we asked, are there criteria that determine whether a settlement agreement is offered? And are there any regulations that allow the resolution of these cases via settlement agreements?

Loophole language correction

We have proposed legislative language that we think would close a loophole in the Registry Law that currently allows so many abusive care providers to avoid placement in the Registry even in cases in which the DPPC affirms, after appeals, that abuse occurred.

The loophole appears to exist in the wide discretion given to the DPPC in determining whether a substantiated incident of abuse was isolated or whether the care provider is nevertheless still fit to provide services.

The Registry regulations state that certain factors, such as prior instances of similar conduct, “may” be considered by the DPPC in the appeal process. We think the DPPC should be required to consider that and other factors if it is to determine fairly whether a given incident was isolated or not. Leaving the decision as to what to consider up to the particular DPPC employee deciding the appeal invites suspicion that the appeal process isn’t necessarily even-handed or fair.

We have contacted the offices of three state legislators who were original co-sponsors of Nicky’s Law, which created the Abuser Registry, and asked them to file corrective legislation. They are Senators Patrick O’Connor, Michael Moore, and Bruce Tarr.

Our suggestion for such language is the following:

1. In considering petitions and appeals filed to avoid placement on the Registry, both the DPPC and DALA must consider the following factors in determining whether the incident was isolated and unlikely to reoccur and the care provider is fit to provide services and supports to persons with intellectual or developmental disabilities:

- The care provider’s employment history in working with individuals with disabilities;

- Prior instances of similar conduct by the care provider;

- Any statements or communication regarding the care provider’s work history and fitness to provide services and supports to persons with disabilities; and

- Any victim-impact statements submitted by individuals with disabilities or their family members or guardians.

2. The DPPC and DALA must place all care providers for whom sexual abuse has been substantiated and affirmed after a petition or appeal process in the Registry.

Earlier this month, a legislative aide to Senator Moore stated that the senator planned to speak with his Senate and House counterparts, as well as leadership and stakeholders, about our suggested language.

We look forward to working with Senator Moore and others in the Legislature to address this issue.

Our priorities for the 2025-2026 legislative session

The 2025-2026 session of the Massachusetts Legislature began on January 1 of this year. So we are taking this opportunity to announce our priorities for this 194th legislative session.

Admissions should be opened to the ICFs and state-operated group homes

We are seeking the filing and passage of legislation that would require the Department of Developmental Services (DDS) to offer the Wrentham Developmental Center, the Hogan Regional Center and state-operated group homes as options for persons with intellectual and developmental disabilities (I/DD) who are seeking residential placements in Massachusetts.

Unless the administration agrees to open those facilities to new admissions, they will eventually close. DDS data show the number of residents or the census at both the Wrentham Developmental Center and Hogan Regional Center continued to drop from Fiscal Years 2019 through 2024.

The census at Wrentham dropped from 323 in Fiscal 2015 to 159 in Fiscal 2024 – a 50% drop. The census at Hogan dropped from 159 in Fiscal 2011 to 88 in Fiscal 2024 – a 45% drop.

Source: DDS

From Fiscal 2008 to 2021, the census in the state-run group home system dropped from 1,059 to 1,023 – a 3.4% decrease.

Meanwhile, the census in the state’s much larger network of privatized group homes continued to climb during that same period, rising from 6,677 to 8,290 — a 24% increase.

Currently, the privatized group home system in Massachusetts is providing substandard care even as thousands of individuals continue to wait for residential placements.

Even the Arc of Massachusetts, which has pushed for the closures of all remaining ICFs, has acknowledged a “systemic failure” in the largely privatized DDS system in which thousands of persons with I/DD are unable to get services.

State-run residential facilities, which have better trained and higher paid staff, are vital to the fabric of care in the DDS system. As Olmstead v. L.C., the landmark 1999 U.S. Supreme Court decision, recognized, there is a segment of the population with I/DD that cannot benefit from and does not desire community-based care. ICFs, in particular, must meet stringent federal standards for care that make them uniquely appropriate settings for persons with the most profound levels of disability and medical issues.

Yet, DDS does not inform individuals and families seeking residential placements that these state-run facilities even exist. During the past two years, we have reported on two admissions to ICFs in Massachusetts (here and here), but those admissions have been the exceptions. In at least two instances in the past two years, families have been unsuccessful in efforts to win placements for their loved ones at the Wrentham Center.

That policy decision by DDS to discourage or block new admissions guarantees that the number of residents in state-run residential care will continue to drop, and that the ICFs, in particular, will eventually be closed.

Right to ICF care

Despite DDS’s policy, the federal Medicaid law and its regulations confer a right to ICF care to individuals and their families and guardians.

As Medicaid.gov, the federal government’s official Medicaid website, explains, “States may not limit access to ICF/IID service, or make it subject to waiting lists, as they may for Home and Community Based Services (HCBS)” (our emphasis).

Open ICF campuses to family housing

In addition to our proposal for legislation to open the ICFs to new admissions, we are calling for legislation that would establish housing on the Wrentham and Hogan campuses for elderly family members of the residents of the facilities.

Such housing would allow families to live in proximity to their loved ones in DDS care and to establish caring communities. It would provide peace of mind to ageing parents and siblings who may find it increasingly difficult to make long trips to visit their loved ones in the facilities.

Adequate funding needed for state-run facilities in the Fiscal Year 2026 budget

In order to preserve ICFs and state-operated group homes, state funding for these settings must be adequate. We are calling for the following increases in the state budget for the coming fiscal year:

- DDS ICF line item (5930-1000). Based on the federal Bureau of Labor Statistics inflation rate of 3.1% in the Boston Metropolitan Area as of November 2024, we are requesting a $3.9 million increase in this line item, from $124,809,632 in the current fiscal year, to $128,678,731 in Fiscal Year 2026.

The ICF line item decreased by 40% between Fiscal 2012 and 2025 when adjusted for inflation.*

- DDS state-operated group home line item (5920-2010). We are requesting a $10.3 million increase in this line item, from $330,698,351 to $340,950,000 in Fiscal 2026.

The state-operated group home line item increased by 47.6% between Fiscal 2012 and 2025 when adjusted for inflation. However, that compares with an increase during that period of 65% in the corporate-provider residential line item (5920-2000). The corporate community-residential line item was $1.7 billion in Fiscal 2025.

ICF budget language should be changed

We are seeking two modifications to the language that is included every year in the ICF line item in the state budget (5930-1000). In one instance, the language mistakenly implies that the U.S. Supreme Court ordered the closures of institutions for persons with developmental disabilities.

In the second instance, the annual budget language lists three conditions for discharging clients from ICFs to the community, but leaves out one of the key conditions in Olmstead, which is that the client or their guardian does not oppose the discharge. We will request that that condition be added to the language in the line item.

Regarding the first instance, the budget language refers to Olmstead v. L.C., the Supreme Court’s landmark 1999 decision, which considered a petition by two residents of an institution in Georgia to be moved to community-based care.

The budget language states that DDS must report yearly to the House and Senate Ways and Means Committees on “all efforts to comply with …Olmstead…and… the steps taken to consolidate or close an ICF…” (our emphasis)

However, as noted above, closing institutions was not the intent of the Olmstead decision. The decision explicitly states that federal law — specifically the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) — does not require deinstitutionalization for those who don’t desire it.

We believe the annual state budget language should be changed to state: “…the steps taken to consolidate or close an ICF and the steps taken to inform families of the choices available for residential care including ICF care.”

We are concerned that the current line item language could allow the administration to justify continuing to underfund the line item, and possibly to seek the eventual closures of the Wrentham and Hogan Centers.

Regarding the second instance in which we are seeking a language change, the three conditions listed in the annual state budget for discharging clients to the community are:

- The client is deemed clinically suited for a more integrated setting;

- Community residential service capacity and resources available are sufficient to provide each client with an equal or improved level of service; and

- The cost to the commonwealth of serving the client in the community is less than or equal to the cost of serving the client in an ICF/IID…”

The first two of those conditions do match conditions listed in the Olmstead decision for allowing the discharge of clients to the community. However, there is a further condition in Olmstead, which is that such a discharge is “not opposed” by the client or their guardian. That condition is not included in the budget language, and we will request that it be included.

Choice needed in residential services

DDS holds considerable authority regarding residential placements. Families cannot change residential providers without DDS approval. We would support legislation creating a voucher system, which would allow family choice, create competition, and improve the quality of care. This would also help families who need to move to other parts of the state for work or family reasons.

Guardianship reform needed

Reform is needed of the guardianship system in probate court, which traps many families into losing disputes with DDS.

We would support a guardianship reform bill that would provide for free legal representation for family members and that would presume that parents or siblings would be suitable guardians in petitioning for guardianships.

We have long supported proposed legislation that would presume that parents, in particular, would be suitable guardians of their adult children with I/DD. This legislation was first proposed by the late Stan McDonald, who had sought unsuccessfully to regain guardianship of his intellectually disabled son.

Stan’s bill, which was most recently filed in the previous legislative session, has never gotten out of the Judiciary Committee, however.

Independent DDS appeals process

The appeals process that persons must follow regarding Individual Support Plans (ISPs) contains a serious conflict of interest in that DDS controls the entire process.

When a family member or guardian of a DDS client appeals the client’s ISP, the DDS commissioner appoints a hearing officer of its choice to decide the case. After the hearing officer decides the appeal, the commissioner can reverse the decision. We have reported on at least two instances in the past year and a half in which this appeals process has been marred by apparent bias on the part of the DDS-selected hearing officer against the appellants.

We would support a bill, which would place the entire ISP appeals process under the control of the independent state Division of Administrative Law Appeals (DALA).

DPPC Abuser Registry reform

Last year, we reported that in only a minority of the cases in which the Disabled Persons Protection Commission (DPPC) affirmed initial substantiations of abuse allegations against care providers did the agency conclude that those persons’ names should be placed in the DPPC’s Abuser Registry.

An individual whose name is listed in the Registry can no longer work in any DDS-funded care setting.

Following our report, state Senator Patrick O’Connor, the original sponsor of the legislation that created the Registry, said he was worried by our findings and that it “may be time to fine-tune” the law.

We are calling for changes in the law that include requiring the DPPC to consider several factors listed in the regulations for determining whether a care provider against whom abuse has been substantiated is really fit to continue to provide services. Right now, the regulations say only that the DPPC “may” consider factors such as previous incidents of abuse and the provider’s previous work history.

Also, we believe the regulations should explicitly require that the DPPC place care providers in the Registry in all cases in which the agency has affirmed allegations of intentional physical or sexual abuse.

Funding to corporate providers must result in higher wages for direct-care workers

Increases in state funding to the providers over the past decade have resulted in continuing increases in the pay of the provider executives. The increased state funding, however, hasn’t been passed through by the providers to their direct care employees.

We are calling for legislation that would raise the pay of direct-care workers employed by DDS corporate providers to $25 per hour.

Work opportunities needed in congregate care settings

In the wake of the closures of all sheltered workshop programs in Massachusetts as of 2016, we are calling for legislation authorizing the introduction of work opportunities for individuals in community-based day programs.

The last time such legislation was proposed appears to have been in 2019 in the form of then H.88. That legislation, however, did not make it out of committee.

Safeguards and corrections needed in Supported Decision Making legislation

During the last legislative session, identical Supported Decision Making (SDM) bills came close to final enactment, but the bills died in the House Rules and House Ways and Means Committees respectively at the end of the session. We had raised numerous concerns about the bills with those and a number of other legislative committees.

We expect the same SDM legislation will be refiled in the current session. We intend to raise similar objections to the bills unless they are redrafted to correct serious flaws.

SDM reflects a growing movement to restrict guardianships of persons with I/DD and replace those guardians with “networks” of more informal advisors. While SDM can hold promise for some high-functioning individuals, and we would support its adoption only with adequate safeguards, particularly safeguards against the potential marginalization of family members.

*From the Massachusetts Budget & Policy Center’s online Budge Browser at https://massbudget.org/budget-browser/.

A compelling new book chronicles a girl’s life at the Belchertown State School

Edward Orzechowski has done it again. He has written a second gripping, as-told-to account of life within the notorious and now long-closed Belchertown State School in western Massachusetts.

The launch of his new book, “Becoming Darlene,” is scheduled for November 23 at 1 p.m. at the Florence Civic Center in Florence, MA.

“Becoming Darlene” is about the life of Darlene Rameau, a former Belchertown resident, as related in a series of interviews with Orzechowski. It follows a similar pattern to that of Donald Vitkus, whose experience before, during, and after Belchertown, was the subject of Orzechowski’s first book, “You’ll like it Here.”

In each case, Orzechowski, a former COFAR Board member, has written the life story of a person who spent most of their childhood at the Belchertown school. When Donald was first sent there in the 1950s, and Darlene in the 1960s, that institution, like a number of others in Massachusetts, was a literal warehouse of abuse and neglect.

It is important to understand that the type of institution that Orzechowski describes in both of his books no longer exists today. Starting in the mid-1970s, while Darlene was still at Belchertown but Donald had long since left it, major upgrades in care and conditions began to be implemented at that and other similar institutions in Massachusetts. These changes were the result of a class action lawsuit first brought by Benjamin Ricci, the father of a former Belchertown resident.

The upgrades were overseen by U.S. District Court Judge Joseph L. Tauro. By the time Tauro disengaged from his oversight of the case in 1993, he wrote that the improvements had “taken people with mental retardation from the snake pit, human warehouse environment of two decades ago, to the point where Massachusetts now has a system of care and habilitation that is probably second to none anywhere in the world.”

As Orzechowski notes, Darlene became aware while she was still at Belchertown of the impact of Tauro’s involvement. Suddenly, and seemingly in one day, new, kinder staff appeared. Restrictions and beatings ended, Darlene says. But those changes still took many years to be fully implemented.

In 1996, Belchertown was closed for good. Today, only two large congregate care facilities remain in Massachusetts — the Wrentham Developmental Center and the Hogan Regional Center. Both centers must meet strict federal standards for care and staffing that were made possible by the federal litigation in Massachusetts and in other states starting in the 1970s.

At Belchertown, Darlene was a keen observer of nonstop human suffering, of wards filled with naked, neglected children, and reeking of urine and feces and infested with insects.

As was the case with Donald Vitkus’s story, much of the story about Darlene is about her attempts to cope in the “real world,” after having been discharged from Belchertown. For both Donald and Darlene, the transition was filled with trials and setbacks. Belchertown continued to affect both of their lives in sometimes tragic ways.

“Becoming Darlene” is a true story, but it reads like a novel. It is a page turner. It is at turns disturbing and heart breaking. But as with Orzechowski’s first book, one finishes this second book with a feeling of gratitude for Darlene and for the triumph of her spirit.

Key lawmaker and disability advocates acknowledge serious problem with state’s Abuser Registry

The original sponsor of the legislation that established an “Abuser Registry” in Massachusetts said it may be time to “fine-tune” the legislation in light our recent report that a potentially significant number of abusive care providers are able to avoid placement of their names in the Registry.

The Registry, which is managed by the Disabled Persons Protection Commission (DPPC), is intended to prevent care providers who have abused persons with intellectual and developmental disabilities (I/DD) from continuing to work for the Department of Developmental Services (DDS) or for any agency funded by DDS.

News Service alone discusses COFAR report that Registry has a possible loophole

The remarks of state Senator Patrick O’Connor, the sponsor of the Registry legislation, and other disability advocates about our findings were reported late last month by the State House News Service. The News Service covers political and governmental issues and events involving the state Legislature and the state administration.

The Registry, which was created under “Nicky’s Law,” has now been in operation for just over three years.

In July, we reported on DPPC data concerning substantiated abuse allegations against care providers since the Registry’s inception. We found that in only a minority of those cases did the DPPC conclude that those persons’ names should be placed in the Registry.

Under Nicky’s Law, care providers, who have been found after DPPC or DDS investigations to have committed abuse, can petition the DPPC to overturn both their abuse substantiations and the placement of their names in the Registry.

We found that of 161 petition decisions, the DPPC affirmed abuse in 132 cases, and reversed abuse substantiations in just 29 cases.

However, even among those 132 cases in which abuse was affirmed through the petition process, only 47 — or 36% — of those providers ended up in the Registry. In contrast, in 85 — or 64% — of those cases, the DPPC determined the abuse was not “Registrable.”

The fact that abuse was not Registrable in most of the substantiated abuse cases appears to be due to a possible loophole in the Registry regulations. The loophole allows DPPC to conclude that an abuse incident was “isolated” and “unlikely to reoccur,” or that the provider is “fit” to continue to provide services to people with I/DD.

As I noted to the State House News Service reporter who had interviewed me for her article, it is difficult, due to the confidentiality of DPPC investigations, to understand the logic behind the DPPC’s decision-making. There seems to be a built-in incentive in the regulations to care providers to petition to overturn any abuse substantiations against them by the DPPC or DDS.

DLC says they have concerns based on our report

The News Service reported that the Disability Law Center (DLC), a federally funded legal advocacy organization in Massachusetts, had previously questioned whether the Abuser Registry regulations were too lenient toward abusive care providers, and whether the regulations may have even gone beyond the scope of Nicky’s Law.

The News Service article quotes Rick Glassman of the Disability Law Center as saying COFAR’s findings are “concerning” to him.

Nicky’s Law sponsor says ‘time to fine-tune’ law

State Senator Patrick O’Connor, the original sponsor of the legislation that led to Nicky’s law, told the News Service that he is worried by our findings and that it “may be time to fine-tune Nicky’s Law.” O’Connor said he intends “to learn more from DPPC about cases in which providers are permitted to stay employed despite committing abuse.

“It’s definitely a cause for concern,” O’Connor added, “and I will for sure be calling for meetings with DPPC to try to get specific examples of why this is happening on both ends to try to figure out how we can make the law better.”

Legislator says COFAR is “inaccurate,” but gives no specifics

State Representative Jay Livingstone, House chair of the Legislature’s Committee on Children, Families and Persons with Disabilities, defended the impact of the Registry to the News Service. Livingstone also alleged that “COFAR’s information is typically not accurate.” He provided no specifics in the News Service article to support that claim.

A month prior to the publication of the News Service article, I sent an email to Livingstone and to State Senator Robyn Kennedy, Senate chair of the Children and Families Committee, and close to 50 other legislators, calling their attention to our report about the Registry.

I have not received a response to date from any of them. Livingston, in particular, didn’t respond to my email. If he has questions about the accuracy of our report, he hasn’t let us know them.

Family member dissatisfied with DPPC investigations

One family member of an individual with I/DD was quoted in the News Service article as saying the DPPC’s investigative process in general isn’t working.

“There’s a lot of cases where these people (abuse investigators) are not doing their jobs,” Jeanne Cappuccio, whose daughter has an intellectual disability, said. “You complain, you file a complaint and it gets screened out. It reinforces that … it’s OK to treat people with disrespect, and it’s OK to be abusive, and it’s OK to mistreat.”

DPPC makes questionable claim about Registry placements

In comments to the News Service, Andrew Levrault, DPPC’s deputy general counsel, defended the Registry’s record and regulations. “We think it (the Registry) has really lived up to its goal to bridge that gap between individuals who would have otherwise had a clean CORI (Criminal Offender Record Information)…(and are now subject to a process) which prevents them from working in the field where they really shouldn’t be because of past abusive conduct,” he said.

Levrault said the instances in which individuals are kept off the Registry include cases in which there is “an opportunity for re-training, including for those who make medication errors.” He maintained that, “In cases of intentional physical or sexual abuse, those providers will be put on the Registry.”

It does not appear, however, that there is anything in the Registry regulations that requires the DPPC to place care providers’ names in the Registry in all cases in which the agency has affirmed allegations of intentional physical or sexual abuse against them.

Our recommendations

We have made a number of recommendations for tightening the Registry regulations, including requiring the DPPC to consider several factors listed in the regulations for determining whether a substantiated incident of abuse really is isolated and whether the care provider really is fit to continue to provide services.

Right now, the regulations say only that the DPPC “may” consider factors such as previous incidents of abuse and the provider’s previous work history.

We also think DPPC should be required to consider impact statements from the victims and their families when considering petitions by care providers to avoid placement in the Registry.

Also, the regulations should explicitly require that the DPPC place care providers in the Registry in all cases in which the agency has affirmed allegations of intentional physical or sexual abuse. Levrault claimed that his already happening, but the regulations don’t appear to support his statement.

The question that remains is how can we ensure that needed changes will happen?

At least some of the lawmakers and advocates interviewed by the State House News Service said the right things about the need to look into our concerns and fine-tune the law.

But at this point, there is little to hold lawmakers and other officials accountable or to ensure that they follow through on their promises.

It is becoming clearer every day that the media is no longer interested in playing that role. The media and our political and governmental leaders are today all part of the same club.

State lawmakers mum about abusive care providers who are avoiding placement in the Abuser Registry

Last week, we brought a concern to the attention of some 50 state legislators that there seems to be a serious problem with the state’s Abuser Registry.

New data we received from the state show that a majority of care providers whom the state has affirmed committed abuse against persons with intellectual and developmental disabilities have nevertheless been able to avoid having their names placed in the Registry.

The lawmakers to whom I sent an email on July 17 containing the link above to our report include the members of the Children, Families, and Persons with Disabilities Committee, the Mental Health, Substance Use and Recovery Committee, and the Health Care Financing Committee.

Those are the principal committees in the Legislature that deal with human services issues.

No response

To date, I haven’t received a response from any of those legislators. I followed up on my original email with a second email on July 18 to the counsel to the Children and Families Committee, and left follow-up phone messages over the past week with the co-chairs of each of the three committees.

It’s not clear to us why none of those lawmakers is willing even to say they will look into our findings. We would hope a potentially serious problem with the Abuser Registry would be of interest to all legislators.

The Abuser Registry was established under “Nicky’s Law” as a means of ensuring that individuals who have been affirmed to have committed “Registrable Abuse” cannot be hired or continue to serve in the Department of Developmental Services (DDS) system even if they don’t have criminal records.

The Registry is a database that the state and its provider agencies must check before hiring new caregiving personnel. Placement of the name of an individual in the Registry means that person is no longer eligible to work for DDS or for any agency funded by DDS.

Data show most abusers’ names not being placed in Registry

We agree that equitable use of the Abuser Registry requires balancing the protection of disabled persons from abuse with due process for accused care providers.

But as we reported, new data we received from the Disabled Persons Protection Commission (DPPC) under a Public Records Law request raise a question whether the scales in that balance might be weighted too heavily in favor of the care providers.

The data show that in only 36% of the cases in which DPPC affirmed initial substantiations of abuse allegations against care providers did the agency conclude that those persons’ names should be placed in the Registry. The DPPC data covered a three-year period since the database was first put into use in July 2021.

The relatively low number of care providers who have been barred from further DDS-funded employment appears to be due to provisions in the Registry regulations that appear to give wide discretion to DPPC to decide whether an individual is fit to continue to provide services.

Even if a Registrable Abuse allegation is initially substantiated against a care provider, the regulations state that the provider can petition the DPPC to argue that they should not be placed in the Registry because the alleged incident of abuse was “isolated and unlikely to reoccur,” and the provider is “fit to provide services.”

Determining whether an incident of abuse was isolated could potentially require DPPC to determine whether the individual had prior abuse allegations lodged against them. But while the regulations state that DPPC may consider information like that, the regulations don’t require DPPC to take any particular factor into consideration.

According to the DPPC data, the names of a total of 102 care providers have been placed in the Registry during the three-year period since the Registry took effect. That is 38% of the total of 266 care providers who received initial notices of substantiated Registrable Abuse in that period.

But the finding that was more concerning to us has to do with the 161 decisions the DPPC made regarding petitions that were filed by care providers to overturn initial abuse substantiations against them.

Of 132 petition cases in which the DPPC ultimately upheld the initial abuse substantiations, the agency concluded that only 47 of those substantiated abusers should have their names placed in the Registry. That is only 36% of the 132 cases.

In 85, or 64% of those cases, the DPPC determined that the abuse wasn’t Registrable, meaning the care provider should not be placed in the Registry. The agency somehow determined in those 85 cases that even though abuse had occurred, those incidents were isolated and unlikely to reoccur and the care provider was fit to provide services.

We supported the Nicky’s Law legislation, which became law in 2020, and continue to do so. But as we said in our post last week, we think the balance between safety due process needs to be adjusted.

You can help find out what’s up with our legislators

Are our legislators who are entrusted with considering and voting on matters affecting the lives of some of the most vulnerable members of our society satisfied with the Registry’s record after three years? If they are satisfied with it, why not say so? If they aren’t satisfied, why not say that?

Below is a list of the legislators whom I emailed last week expressing our concern about the Registry. Lawmakers who serve on more than one of the committees listed below are listed only once.

If any of these legislators represents your district, please feel free to email them and forward this link to our previous post, even though they should already have it. (Don’t feel you have to email more than your own senator or representative, or more than one or two of the co-chairs of the three committees. We would suggest that you email one legislator at a time.)

Ask for a response, and, if you get one, please let us know what they have to say.

Children, Families, and Persons with Disabilities Committee

Sen. Robyn Kennedy, co-chair, Robyn.Kennedy@masenate.gov

Rep. Jay Livingstone, co-chair, Jay.Livingstone@mahouse.gov

Sen. Becca Rausch, vice chair, Becca.Rausch@masenate.gov

Rep. Jessica Giannino, vice chair, jessica.giannino@mahouse.gov

Sen. Lydia Edwards, lydia.edwards@masenate.gov

Sen. James Eldridge, James.Eldridge@masenate.gov

Sen. Paul Mark, Paul.Mark@masenate.gov

Sen. Patrick O’Connor, Patrick.OConnor@masenate.gov

Rep. Rita Mendes, Rita.Mendes@mahouse.gov

Rep. Michelle Ciccolo, michelle.ciccolo@mahouse.gov

Rep. Adrianne Ramos, Adrianne.Ramos@mahouse.gov

Rep. Carol Doherty, carol.doherty@mahouse.gov

Rep. David LeBoeuf, david.leboeuf@mahouse.gov

Rep. Natalie Higgins, Natalie.Higgins@mahouse.gov

Rep. John Moran, john.moran@mahouse.gov

Rep. Donald Berthiaume, Donald.Berthiaume@mahouse.gov

Rep. Alyson Sullivan, alyson.sullivan@mahouse.gov

Mental Health, Substance Use and Recovery Committee

Sen. John Velis, co-chair, john.velis@masenate.gov

Rep. Adrian Madaro, co-chair, Adrian.Madaro@mahouse.gov

Sen. Julian Cyr, vice chair, julian.cyr@masenate.gov

Rep. Michelle DuBois, vice chair, Michelle.DuBois@mahouse.gov

Sen. Nick Collins, Nick.Collins@masenate.gov

Sen. Brendan Crighton, brendan.crighton@masenate.gov

Sen. John Keenan, John.Keenan@masenate.gov

Rep. Sally Kerans, Sally.Kerans@mahouse.gov

Rep. Christopher Markey, Christopher.Markey@mahouse.gov

Rep. Michael Kushmerek, Michael.Kushmerek@mahouse.gov

Rep. Simon Cataldo, Simon.Cataldo@mahouse.gov

Rep. Tram Nguyen, tram.nguyen@mahouse.gov

Rep. Kate Donaghue, Kate.Donaghue@mahouse.gov

Rep. Susannah Whipps, Susannah.Whipps@mahouse.gov

Rep. Steven George Xiarhos, Steven.Xiarhos@mahouse.gov

Health Care Financing Committee

Sen. Cindy Friedman, co-chair, Cindy.Friedman@masenate.gov

Rep. John Lawn, co-chair, John.Lawn@mahouse.gov

Sen. John Cronin, vice chair, John.Cronin@masenate.gov

Rep. Kathleen LaNatra, vice chair, kathleen.lanatra@mahouse.gov

Sen. Paul Feeney, paul.feeney@masenate.gov

Sen. John Keenan, John.Keenan@masenate.gov

Sen. Jason Lewis, Jason.Lewis@masenate.gov

Rep. Brian Murray, Brian.Murray@mahouse.gov

Rep. Steven Ultrino, Steven.Ultrino@mahouse.gov

Rep. Christine Barber, Christine.Barber@mahouse.gov

Rep. Lindsay Sabadosa, lindsay.sabadosa@mahouse.gov

Rep. Patricia Duffy, Patricia.Duffy@mahouse.gov

Rep. Kip Diggs, Kip.Diggs@mahouse.gov

Rep. Jack Lewis, Jack.Lewis@mahouse.gov

Rep. Christopher Worrell, Christopher.Worrell@mahouse.gov

Rep. Hannah Kane, Hannah.Kane@mahouse.gov

Rep. Mathew Muratore, Mathew.Muratore@mahouse.gov

Rep. F.J. Barrows, fred.barrows@mahouse.gov

Thanks!

Even after affirming abuse, DPPC places care providers in Abuser Registry only 36% of the time

When an “Abuser Registry” was authorized in Massachusetts with the enactment of “Nicky’s Law” in 2020, we joined many others in welcoming it as a major step forward in ensuring adequate and safe care for persons with intellectual and developmental disabilities.

Under the law, the names of caregivers against whom abuse and neglect allegations are substantiated are placed in the Abuser Registry — a database that the state and its provider agencies must check before hiring new personnel. Placement of the name of an individual in the Abuser Registry means that person is no longer eligible to work for the Department of Developmental Services (DDS) or for any agency funded by DDS.

Equitable use of the Abuser Registry requires balancing the protection of disabled persons from abuse with due process for accused care providers.

But new data we have received from the Disabled Persons Protection Commission (DPPC) under a Public Records Law request raise a question whether the scales in that balance might be weighted too heavily in favor of the care providers.

The data show that in only 36% of the cases in which DPPC affirmed initial substantiations of abuse allegations against care providers did the agency conclude that those persons’ names should be placed in the Registry.

The DPPC data covered a three-year period since the database was first put into use in July 2021.

The chart below summarizes our analysis of the DPPC data.

The Registry statute and regulations differentiate between individuals who are referred to as “caretakers” and those who are “care providers.” Only names of care providers can be placed in the Registry.

A care provider is a person who is employed by either DDS or an agency that contracts with DDS to provide services to persons with intellectual or developmental disabilities. Care providers can include volunteers.

If DPPC initially substantiates an abuse allegation and determines that the abuser is a care provider, DPPC notifies that individual of a substantiated finding of “Registrable Abuse.”

Caretakers, who include family members and others persons who are not employed by DDS or its contractors, can be investigated by DPPC and DDS for abuse; but they are not subject to placement in the Registry.

DDS and its contracting service agencies must check the Registry prior to hiring care providers.

As part of the effort to ensure due process, the Registry statute and regulations allow care providers, against whom Registrable Abuse allegations have been initially substantiated, to file petitions with DPPC to prevent their placement in the Registry.

The DPPC data show that during the three-year period since the inception of the Registry, DPPC upheld initial abuse findings involving 132 care providers who had filed petitions challenging those substantiations; yet the agency determined that only 47 of those care providers should have their names placed on the Registry. In 85 of those cases, the agency concluded that the care providers were still fit to continue providing services.

The relatively low number of care providers who have been barred from further DDS-funded employment appears to be due to provisions in the Registry regulations that appear to give wide discretion to DPPC to decide whether an individual is fit to continue to provide services.

Even if a Registrable Abuse allegation is initially substantiated against a care provider, the regulations state that the DPPC can decide not to place that individual in the Registry if the alleged incident of abuse is found to be “isolated,” or if the provider is found to be “fit to provide services.”

Determining whether an incident of abuse was isolated could potentially require DPPC to determine whether the individual had prior abuse allegations lodged against them. But while the regulations state that DPPC may consider information like that, the regulations don’t require DPPC to take those particular factors into consideration.

Confirmed abusers not necessarily placed in the Registry

When a care provider petitions DPPC to overturn an initial finding of Registrable Abuse, one of three things can happen. DPPC can:

- Determine that the abuse substantiation was not supported by a preponderance of the evidence. In that case, the substantiation finding is reversed, and the care provider’s name is not placed in the Registry.

- Uphold the abuse substantiation, but determine that the incident was isolated and unlikely to reoccur, and that the care provider is fit to provide services to persons with disabilities. In that case, referred to as a “split decision,” the care provider’s name is similarly not placed in the Registry.

- Determine that the substantiation is supported by a preponderance of the evidence and that the care provider has not shown that the incident was isolated or that they are fit to continue to provide services. In that case, the care provider’s name is placed in the Registry.

If a care provider does not file a petition to overturn a Registrable Abuse substantiation, their name is automatically placed in the Registry.

In our view, the second outcome above involving consideration of care provider petitions is problematic. How does DPPC determine whether an incident of abuse is unlikely to reoccur or that a caregiver is fit to continue to provide services?

Under the regulations, there are a number of factors that DPPC may consider, including whether the care provider “received training relevant to the incident at issue”; the care provider’s employment history in working with individuals with disabilities; prior instances of similar conduct by the care provider; any statements or communication regarding the care provider’s work history and fitness to provide services; and whether the care provider’s conduct “could reasonably be addressed through training, education, rehabilitation, or other corrective employment action and the care provider’s willingness to engage in said training, education, or other corrective employment action.”

But as noted, the regulations say only that each of these criteria may be considered by the DPPC, not that they must be considered. At least some of these criteria also seem vague and potentially easy to establish.

So it’s not necessarily the case that DPPC, for instance, would consider prior instances of similar conduct in determining whether to approve or deny a petition to overturn a Registrable Abuse substantiation. As a result, it seems that the regulations may provide care providers with a relatively easy path to avoid placement in the Registry.

The DPPC doesn’t agree with our conclusions. An attorney with the DPPC defended the Registry statute and regulations, saying they were “drafted with input from various stakeholders to balance the safety of persons with I/DD (intellectual and developmental disabilities) and the due process rights of care providers.”

The DPPC attorney added that the agency “believes that the seven enumerated but non-exhaustive factors in (the regulations) are neither vague nor do they present an ‘easy path’ for exclusion from the registry. Each Petition is carefully analyzed based on its unique circumstances.”

Our analysis of the data

We analyzed DPPC data concerning Registrable Abuse for Fiscal Years 2022, 2023, and 2024, the years that the Registry has been in existence.

The DPPC data show an average of 13,500 allegations of abuse were filed each year, but DPPC “screened in” only an average of 2,400 of them per year for investigation over the three-year period. Of those screened-in allegations, DPPC and DDS initially substantiated Registrable Abuse involving 266 care providers.

Of those 266 care providers who had Registrable Abuse substantiated, 180, or 67%, filed petitions with DPPC, contesting the substantiations. The names of the remaining 86 providers, who didn’t contest the abuse substantiations, were automatically placed in the Registry.

The data show that over the three-year period, DPPC issued decisions in 161 of the 180 petition cases. As of June 17 of this year, 19 of those cases were still pending.

According to the data, DPPC upheld the initial abuse substantiations in 132, or 82%, of the 161 petition decisions. However, in 85, or 64%, of the 132 cases, the agency determined that the abuse wasn’t Registrable, meaning the care provider was fit to continue providing services and should not be placed in the Registry. Those were so-called split decisions.

In only 47 of the 132 cases, in which abuse substantiations were upheld, did DPPC determine that the care providers’ names should be placed in the Registry.

The data further show that a total of 24 care providers, against whom DPPC had affirmed Registrable abuse, exercised their additional right under the regulations to appeal to the Division of Administrative Law Appeals (DALA), an independent state agency that conducts adjudicatory hearings. DALA overturned DPPC’s decisions in only 2 of those 24 appeals.

According to the data, a total of 102 names of individuals were placed in the Registry during the three-year period. That is 38% of the total number receiving initial notices of substantiated Registrable Abuse.

We think the DPPC regulations need to be made more stringent to ensure that while due process should remain for care providers who are accused of abuse, unfit providers do not continue to work in the DDS system.

In considering care provider petitions, DPPC should be required to consider all of the enumerated factors in the regulations, particularly a care provider’s previous incidents of abuse and previous work history. Those factors are critically important in determining whether a given incident of abuse is isolated or not. Leaving it to DPPC’s discretion whether to consider those factors invites distrust of the agency’s decisions.

We also think DPPC should be required to consider impact statements from the victims and their families.

Registry established because of paucity of criminal convictions

Prior to the establishment of the Registry, caregivers in Massachusetts were prevented by law from working in DDS-funded facilities only if they had prior criminal convictions. However, even when abuse against persons with developmental disabilities is substantiated by agencies such as the DPPC, it does not usually result in criminal charges.

Thus, the Abuser Registry was intended to ensure that individuals who have been affirmed to have committed Registrable Abuse cannot be hired or continue to serve in the DDS system even if they don’t have criminal records.

We believe that in this respect, the establishment of the Abuser Registry was a major step forward in the care of persons with intellectual and developmental disabilities. But we think the balance between safety of those individuals and due process that is afforded to their care providers needs to be adjusted.

State legislators could help change the culture in DDS. Will they?

More than a month ago, we brought a case involving the apparent neglect of a resident of a provider-run group home and the intimidation of his family to the attention of the co-chairs of the Legislature’s Children, Families, and Persons with Disabilities Committee.

Then on March 5, I forwarded a follow-up post about the case to the committee co-chairs, Senator Robyn Kennedy and Representative Jay Livingstone.

We think the case illustrates a disturbing and ongoing state of dysfunction in the state’s system of care of persons with intellectual and developmental disabilities (I/DD). It seems that the Department of Developmental Services (DDS) is doing little or nothing to change a culture in the system that appears to foster this level of neglect and intimidation.

As our posts reported, Rachel Surner informed the upper management of her son’s corporate provider-run group home in June 2022 of an incident in which the staff neglected to give her son Ian his portable urinal. Ian, 31, has spastic quadriplegia, a condition that has left him with the limited ability to move only his arms.

Having received distress texts on her phone from her son, Rachel had to go to the home herself at 6:45 in the morning to retrieve his urinal from the floor next to his bed.

Then in January of this year, the same thing happened again when the same staff member again allegedly neglected to give Ian his urinal. The response of the provider, the Justice Resource Institute (JRI), however, was to blame Rachel for allegedly being “disruptive” in the home, and to impose severe restrictions on her visits to her son.

DDS stated that Rachel and her husband would either have to comply with those restrictions or remove Ian from the home.

Rachel had complained about numerous other problems in the home as well, including a failure to regularly shower or toilet Ian, and a failure to involve him in community activities.

On February 12, I talked to a member of Senator Kennedy’s staff at a meeting she held with constituents in my hometown of Berlin, MA, and gave her information about Ian’s case and that of another mother whose son was also severely neglected in a provider-run group home.

In that second case, the son had suffered extreme dental decay, weight loss, removal of prescribed medications, and unexplained injuries. The aide said she would bring the cases to Senator Kennedy’s attention.

Not having heard anything more by the beginning of this month, I stated in my March 5 follow-up message to both Kennedy and Livingstone and their staffs that we would be happy to arrange for our members to provide them with further information about the ongoing problem of abuse and intimidation in the DDS system.

Even The Boston Globe has written about this culture, noting earlier this year that when parents of children with autism have complained about abuse and neglect in DDS-funded group homes, they have been labeled as “too demanding.” And a number of parents who spoke to the newspaper requested anonymity because “they were afraid that state officials or providers would retaliate against them.”

Obligation to change the DDS culture and system

We think legislators have an obligation to help change a culture within DDS that appears to perpetuate poor care and intimidation of families in the provider-run group home system. As co-chairs of the Children and Families Committee, Kennedy and Livingstone are in a position to exert pressure on DDS to change that culture.

Last fall, we first met with both Senator Kennedy and Representative Livingstone on Zoom to make a case for the preservation of state-run residential services. In our view, state-run services are more accountable to both families and taxpayers than are corporate provider-run services.

Levels of abuse and neglect in the Wrentham and Hogan facilities are significantly lower than in the provider-run group home system, based on a review of state data that we undertook.

On a per-client basis, state-operated group homes were well below average in terms of both substantiated allegations of abuse and criminal referrals between Fiscal 2010 and 2019. Also, we found that the state-run Wrentham and Hogan Intermediate Care facilities were at or near the bottom of the list of total providers in those measures.

Yet, the Wrentham and Hogan Centers and the state-run group homes are ultimately facing closure because a succession of administrations has largely closed their doors to new admissions.

Last fall, Senator Kennedy said she would help us arrange a meeting with Governor Healey in which we would raise these concerns. We urge people to email Kennedy’s and Livingstone’s offices, and forward a link to this blog post.

You can email them at Robyn.Kennedy@masenate.gov and Jay.Livingstone@mahouse.gov.

Remind them that it is time to change the culture in DDS and to take concrete steps, including setting up a meeting with the governor, to preserve state-run services in the DDS system.

Thanks!

Mother says neglect and intimidation continued at her son’s group home

More than a year and a half ago, Rachel Surner informed the upper management of her son’s group home in Ashland of a disturbing incident in which the staff neglected to give her son, Ian Murawski, his portable urinal.

Rachel had to come to the house herself at 6:45 in the morning in June 2022 to retrieve the urinal, which was on the floor next to Ian’s bed. She said she was met at the door with resistance and intimidation by a staff member on duty.

Ian, 31, has spastic quadriplegia, a condition that has left him with the limited ability to move only his arms. Despite that, Ian, who has an intellectual disability, is an engaging young man with a major musical singing talent.

Rachel also informed the Department of Developmental Services (DDS) about the June 2022 incident, and a range of other problems in the group home, which is run by the Justice Resource Institute (JRI), a corporate DDS provider. But nothing was ever done to improve the situation, she said.

Following an almost identical incident in January of this year in which the same staff member again neglected to give Ian his urinal, Rachel said JRI’s response was to blame her for allegedly being “disruptive” in the home.

JRI then imposed severe restrictions on her visits to her son, and DDS stated that she and her husband would either have to comply with those restrictions or remove Ian from the home.

Rachel and her family chose the latter course. They took Ian home last month to live with them.

They are seeking another placement, and are interested in the Wrentham Developmental Center or possibly a state-operated group home. But, Rachel said, DDS has provided few answers to their questions about those options.

As we argue below, we believe that in issuing the visitation restrictions, JRI violated DDS regulations ensuring a right to visitation. Also, we think DDS violated its transfer regulations that prevent the termination of residential services to individuals without due notice and due process.

This is one of many cases in which providers and DDS appear to have placed the blame on family members for being disruptive or overly demanding when they have attempted to advocate for their loved ones in group home settings. (See here, here, and here.) In all of these cases, DDS has appeared to side with provider staff against the families when those families are simply complaining about substandard care.

‘Passive-aggressive torture”

Rachel and her husband, who deny having ever caused a disturbance in the home, said the latest incident in January occurred after her son had called her repeatedly, screaming and “in crisis.”

Ian, who is high-functioning despite his disability, takes medication for extreme anxiety and depression, which can reach levels high enough to cause psychosis, Rachel said. However, the staff didn’t give the medication to Ian regularly because they didn’t pay enough attention to him to recognize his symptoms of anxiety, she said.

According to a DDS complaint intake letter about the January 21 incident, Rachel went to the house from her home in Holliston at 11:30 p.m. after being unable to reach the staff by phone. A JRI attendant on call, whom she also had contacted, had told her that Ian was asleep. Rachel said she knew this wasn’t the case as Ian was still calling and texting her in distress.

When she entered the house, she found that Ian was awake in his bed, which had been left in an upright position. He had no remote controls for adjusting the bed, no urinal, no water, and the overhead light had been left on. Without access to the remote controls, there was no way Ian could adjust his bed or get to sleep.

According to the intake letter, a staff member, meanwhile, was lying under covers with a pillow on a couch in the living room, and was speaking on a phone in a foreign language. When Rachel asked repeatedly where the remote controls were, the staff member refused to answer and said he was on a call. At that time, Rachel pulled her phone out of her back pocket to call her daughter, and the staff person then lunged at her to grab it from her, the intake letter stated.

This was the same staff member, according to Rachel, who had neglected in the previous incident in June 2022 to give Ian his urinal. The January 2024 intake letter quoted Rachel as referring to the failure to give Ian his remote controls and urinal as “a passive-aggressive form of torture.”

The latest incident is under investigation by the Disabled Persons Protection Commission (DPPC).

June 2022 incident

As we reported last April, Ian repeatedly texted Rachel early one morning in June 2022 from the group home that he needed to urinate, but couldn’t locate his portable urinal.

Rachel said she tried to call the house, but the phone was off the hook; so at 6:45 a.m. on a Sunday morning, she drove there. As she waited for someone to answer the door, she could hear Ian crying for help.

Rachel said the same staff member, who later neglected to provide Ian with his urinal and remote controls in January of this year, came to the front door, but refused at first to let her in. She went past him into the house, and went to her son’s room where she saw that his urinal, which was supposed to be on his bedside table, was on the floor.

Rachel said that when she then tried to leave the room to give Ian privacy, the staff member initially blocked the door to the bedroom and wouldn’t move to let her out. He later moved away slightly, but she felt threatened and intimidated by his actions.

She said she later asked the staff member why he didn’t respond to Ian’s plea for help, to which he replied that Ian “’never told us he needed help.’” She said she replied to the staff member that she could hear Ian’s cries for help while she was standing at front door.

Problems not corrected

Rachel said neither JRI nor DDS made efforts to correct problems in the group home, such as the urinal incidents, that she brought to their attention. One other example of that was her discovery in July of 2023, after bringing Ian home from a musical gig at a restaurant in Ashland, that overnight staff in the home appeared to be asleep in the living room when they arrived. As noted above, she said that issue continued through this past January.

Other ongoing problems have included:

Hygiene neglect

Rachel said Ian went for days with no shower or toileting in the group home. He also went for days without having his teeth brushed. His bed linens filthy, she said, and he was often dressed in same clothing as the day before. His finger and toenails were often unclipped, and he was often not shaved.

Lack of socialization, activities, and community involvement

Rachel contends the staff rarely took Ian out of the house on community outings. She said this was due to the staff’s lack of involvement in general with him. She noted that Ian needed far more care than the other clients in the home who are all able-bodied.

Visitation restrictions violated DDS regulations

Rachel said that after the incident on January 21 of this year, JRI’s response was to issue visitation restrictions against her, which both she and a JRI program director were supposed to sign.

A copy of the unsigned and undated visitation restrictions contains the introductory statement that, “Inappropriate and disruptive behavior creating an environment detrimental to program services have occurred during visits of Rachel Surner to (the group home).”

Rachel maintains that statement is completely untrue. She maintains that neither she nor any other members of her family were ever disruptive in the home.

Rachel was then supposed to agree to the following restrictions:

- Visits may occur no more than once per day for a maximum of one hour per visit.

- No video recording of staff or other individuals may take place during the visit. (Rachel maintains she never recorded staff, but live videotaped her visits so family members could be witnesses to interactions in the home.)

- Drop-offs without entering the home or property must also be scheduled in advance with JRI management and are limited to 10 minutes.

- Parking on the street outside the property is prohibited except during agreed-upon visits.

- JRI may deny plans for any visit if it is not deemed necessary or it is detrimental to the program.

- JRI staff have the right to terminate a visit at any time. I (Rachel) agree to leave peacefully when requested or required to do so.

Rachel said the DDS assistant area director stated to her that she would have to agree to the restrictions in order for Ian to continue to live in the group home.

In our view, JRI, in issuing the visitation restrictions, was acting in violation of DDS regulations, which permit visitation by a guardian “to the maximum extent possible.” According to the regulations, “Reasonable restrictions” may be placed on the visits “to avoid serious disruptions in the normal functioning of the provider.”

Given that Rachel denies that her family ever caused any disruptions, we think DDS should have given the Surners a chance to rebut the allegation. That didn’t happen.

We also think DDS violated the Department’s transfer regulations, which prohibit the Department from terminating a residential placement without giving 45 days’ notice, specifying an alternative location and obtaining the guardian’s consent to it.

Desire for a new placement

Rachel said that since Ian’s discharge from the group home, he is not currently receiving any services from the Department. She said that while DDS did provide her with a list of other group homes, the Department has not answered many of her questions about the list.

This case is one of many demonstrating that the DDS-funded provider-run residential system has become dysfunctional. Problems identified by family members are not corrected, but the family members themselves often become the focus of blame.

DDS has consistently also blamed these problems on staffing shortages. But that doesn’t explain why the Department apparently didn’t act in this case to ensure that overnight staff were not sleeping on the job, or that the staff treated Ian with dignity and respect. Repeated failures to provide a portable urinal to a person with quadriplegia is inexcusable, and is rightly being investigated as abuse by DPPC.

Inadequate staffing also doesn’t explain why the Department would agree to an excessively restrictive visitation policy against the family, or why the Department didn’t seek Rachel’s response to the charge that she was being disruptive in the home.

DDS needs to reexamine and change its culture. In our view, this is a key test for the Healey administration.

Globe update report has devastating findings about DDS provider-run group home system. Is the administration listening?

In the second of two reports on the corporate, provider-based group home system in Massachusetts, The Boston Globe last week characterized the system as “hobbled by poor staffing and struggling with allegations of abuse and neglect.”

Last week’s article was a follow-up to a report in September by the Globe’s Spotlight Team, which had focused on widespread abuse and neglect in provider-run residential schools for children and teens with autism.

We think the Globe’s reporting raises some important questions, one of which is whether the Healey administration and the Legislature are listening.

The Globe’s reporting echoes assertions about abuse and neglect in the system that we have been making for years. Moreover, we think the Globe is on the right track in noting a key factor plaguing the system, which we have long emphasized, of underpaid and undertrained staff.

Last week’s Globe article stated that most of the parents of autistic children whom the paper had interviewed asserted that, “Massachusetts has never solved long-term systemic problems of low pay and inadequate training” in the system.

The paper noted that although “the state has directed millions of dollars to group home providers to help them recruit and keep staff, pay remains similar to that of some retail and fast food workers; $17 to $20 an hour is typical.”

The Globe further stated that “a number of parents who spoke with (the newspaper) requested anonymity because they were afraid that (as we have long reported) state officials or providers would retaliate against them or their child if they spoke out.”

Paper needs to examine the causes

We hope the Globe will investigate the causes of that culture of retaliation and intimidation of families who complain about inadequate care and even abuse and neglect of their loved ones; and that it will investigate the causes of the underpayment of staff.

Understanding the causes of the underpayment of staff might help explain where the millions of taxpayer dollars went, given the money, as the Globe implied, doesn’t appear to have been used to raise staff wages to any significant degree. It might also explain why direct-care workers in the provider system have historically been underpaid and undertrained.

We think an investigation of the causes will reveal that the corporate provider system has always been been about making as much money as possible for its executives while paying its direct care workers as little as possible. That appears to explain why the privatization of human services has never met the promise of both delivering high-quality care and saving money. It may also explain why continual efforts to raise the pay of direct care workers don’t seem to lead to that result (see Massachusetts Inspector General’s 2021 Annual Report, page 27).

State-run services ignored as potential solution

Last week’s Globe article referred to concerns raised by the Arc of Massachusetts and the Massachusetts Association of Developmental Disabilities Providers (ADDP) — both of which actually lobby for the providers — about the shortage of staff and a lack of available group homes.

But while organizations like the Arc and the ADDP publicly decry the poor care and abuse of clients and the underpayment and shortage of staff, they both oppose a key potential solution to the problem, which would be to open the doors of the Wrentham and Hogan Developmental Centers and provide state-operated group homes as options to individuals seeking residential placements.

The state-run Wrentham and Hogan Centers and state-operated group homes have better trained and better paid staff than the provider-run homes. Yet the state-run facilities are losing population even as the number of people waiting for placements is growing. That is because the administration is not offering state-run facilities as options to people seeking placements, and is even denying requests made by families to place their loved ones in them.

The Arc and the ADDP appear to offer no solutions to those problems other than to ask the state to direct more money to them. In our view, those problems will never be solved unless the state changes the incentives driving privatized care.

Real oversight needed

In addition to providing families with state-run facilities as options for residential care, the state needs to take steps to ensure that group home providers really do raise the pay of their direct-care workers. It could begin to do that by establishing true financial oversight of the provider system. Currently, that oversight is practically non-existent.

Successive administrations and the Legislature have been committed to the privatization of DDS care for decades. They have maintained an extraordinarily close relationship with the corporate provider system in that respect. As noted, the Globe pointed out that both DDS and the providers often retaliate against parents and family members who dare to complain about poor care in the group homes.

We hope the Healey administration will not allow the anti-family culture and the continuing underpayment of direct-care staff in the DDS provider system to continue. We also hope the administration will consider reversing the longstanding administration policy of allowing state-run residential facilities to die by attrition.

The breakdown of the DDS system caused by decades of runaway privatization and mismanagement is finally being reported by the Globe. We hope the Healey administration is listening.

Latest Supported Decision Making bill offers no improvements over previous versions

We first pointed out problems seven years ago with a bill in the state Legislature that would authorize Supported Decision Making (SDM) in Massachusetts.

SDM involves written agreements to replace guardians of persons with developmental disabilities with informal teams of “supporters” or advisors.

Each year, SDM legislation has gotten closer and closer to final passage in the Legislature; and yet, as far as we can see, the proponents of the bill have not made what we argue are needed changes or improvements to the versions of the bill that they have continued to file.

This year’s version of the bill, S. 109, is no exception. In our view, it has the same problems as the previous versions.

Last year’s version of the bill (S. 3132) passed the Senate in November and died in the House Ways and Means Committee, just one step away from final passage in the full House. At the time, we had urged the Ways and Means Committee not to send the bill to the House for final passage.

As we noted in a previous post about that bill, it lacked provisions to protect the rights of persons with intellectual and developmental disabilities, and their families and guardians.

S.109, this year’s version, is now before the Children, Families, and Persons with Disabilities Committee. We are similarly asking the Committee this year not to advance the bill in the legislative process without making needed changes to it.

Under the bill, an SDM “supporter” or “supporters” would help an individual with an intellectual disability, known as the “decision-maker,” make key life decisions, including decisions about their care and finances. Most people with developmental disabilities currently have guardians, most of whom are family members of those individuals. But SDM proponents maintain that guardianship, even when guardians are family members, unduly restricts an individual’s right to make those decisions.

But persons with severe and profound levels of intellectual disability have greatly diminished decision-making capacities. We think many of those people are likely to be vulnerable to coercion and financial exploitation from persons on their SDM teams who may “help” them make financial decisions that don’t reflect their wishes.

In these situations, family members of persons with developmental disabilities, whom we have found to be likely to act in the best interest of their loved ones, may find themselves outvoted on the support teams by other team members who may stand to benefit financially from the clients’ “decisions.”

Legislation still does not provide a standard for judging the decision-making capacity of the individual

In our view, a key piece missing from the SDM legislation so far has been a standard for the level of intellectual disability above which an individual can reasonably be considered to be capable of making decisions with “support” from clinicians, paid caregivers, and other SDM team members.

As was the case with previous versions of the bill, S.109 defines the “decision-maker” as “an adult who seeks to execute, or has executed, a supported decision making agreement with one or more supporters…”

There is no further specification about the decision maker in the bill. There is no differentiation in the definition between individuals with greater or lesser degrees of intellectual disability, and no consideration whether persons with low levels of cognitive functioning are really capable of making and appreciating life-altering decisions.

As a 2013 article on SDM in the Penn State Law Review stated,